Adipose tissue macrophages in aging

- Metabolic pathways are not only involved in the fulfilment of all bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands of cells but also integrate into the signalling cascades regulating cellular function. The molecular mechanisms that sense metabolic status of cell and regulate cellular functions are termed as metabolic checkpoints.

- Age-associated immunological dysregulation potently modulates systemic inflammation, multiorgan dysfunction, and longevity where adipose tissue play important role. One of the main factors associated with obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation is dysregulation of the immune cell populations within the tissue stromal fraction. Therefore understanding the role of adipose- resident immune cells and the interplay between metabolic and inflammatory processes in ageing adipose tissue holds significance.

- Age-dependent changes affect the organism’s ability to maintain homeostasis and to effectively tackle the stress across a variety of cells which associates with the increased incidence of various diseases in aged population. Age-related changes in the immune system are broadly referred to as immunosenescence which include persistent low-grade inflammation (inflammaging), impaired ability to effectively respond to new antigens, increased incidence of autoimmunity, impaired wound repair and decreased ability to fight infection or cancer[1].

- Aging is associated with a decrease in the cellularity of the bone marrow. Hematopoietic stem cells increase in frequency and exhibit the potential for myeloid-biased differentiation while down-regulating genes for lymphoid specificity and function with age. Similarly, thymus also undergoes thymic involution and decline in its functions. The thymic compartments show a decrease in cortical and medullary volumes, changes in epithelial cell architecture and the stroma is predominantly substituted by adipose tissue [2].

- Adipocytes can communicate directly with immune cells through cell–cell interactions. Adipocytes express the classical antigen presenting molecule MHC I, while MHC II is rapidly induced by inflammatory stimuli[3]. It is shown that large adipocytes highly express MHCII and function as antigen presenting cells in adipose tissue to stimulate IFN-γ-expressing CD4+ T cells. These findings suggest that adipocyte hypertrophy, rather than overall obesity, is the major contributor to adipose tissue inflammation[4]. Adipocytes also express the lipid–antigen presenting molecule CD1d, known to mediate interactions with iNKT cells. Thus the adipocytes are the predominant antigen presenting cells in adipose tissue[5].

- Macrophages are the main leukocyte in regulation of inflammatory processes and present in the adipose stromal fraction of adult, non-obese mice and humans[6]. Monocytes migrate to the adipose tissue in response to chemokine CCL2 where they differentiate to macrophages in response to growth factors, including macrophage colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Adipocyte derived factors such as CCL5, RANTES, IL6, IFNγ and TNFα drives the polarization of macrophages into highly inflammatory, classically activated referred to as M1- macrophages[7].

- Macrophages can be increasingly dysregulated with aging with respect to their phenotypes and functions. Inflammatory mediators (TNF and IL-6) were increased in macrophages upon aging. This increased inflammatory response by macrophages was associated with increased expression and activation of components of the NLRP3 inflammasome[8]. In addition, the production of PGE2, and expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) which contributes to age-associated suppression of T cell function, is generally increased in murine peritoneal macrophages with aging. The expression of transglutaminase-2, an M2 marker also increases in macrophages suggesting increase in M2 polarization of tissue macrophages in steady state upon aging [9].

Inflammasomes in inflammaging

- The inflammasome is a multiprotein oligomer responsible for the activation of inflammatory responses. The inflammasome promotes the maturation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. The secretion of these cytokines results in pyroptosis, a form of programmed pro-inflammatory cell death distinct from apoptosis. Inflammasome contains a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor, especially a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) or an absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptor. Activation of the pattern recognition receptor NLRP3 leads to recruitment of the adapter apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC), resulting in the activation of pro-caspase-1 into its cleaved form. Caspase-1 plays a role in the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 into active cytokines and the initiation of pyroptosis by autocatalysis and activation[10].

- The aberrant activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is associated with the pathogenesis of various autoinflammatory, autoimmune, and chronic inflammatory and metabolic diseases, including gout, Muckle-Wells syndrome, alzheimer’s disease, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, obesity and aging. Thus, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome should be tightly regulated to prevent unwanted host damage and excessive inflammation.

- The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by a variety of PAMPs and DAMPs, originating from numerous pathogens, a large number of pore-forming toxins, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and particulate crystals and aggregates. Gout-associated etiologic agents, such as uric acid crystals and calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystals can lead to the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β and IL-18. Environmental crystalline structures, including silica, asbestos, aluminum salt crystals, and the adjuvant aluminum hydroxide are also able to trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation [11].

- AIM2 is referred to as the DNA inflammasome for its ability to detect foreign cytosolic dsDNA, using a HIN200 (hematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear antigens with 200 amino acid repeats) domain (encoded by IFI16) attached to a pyrin domain (PYD), which it uses to recruit the adaptor protein ASC during inflammasome formation. Cytosolic DNA can trigger both signal 1 (expression of inflammasome platforms and substrates) for AIM2 via cGAS-STING and signal 2 that leads to the post-translational assembly of the AIM2 inflammasome. Inflammasome activation by AIM2 is amplified by the activation of a Type I interferons[12].

- Macrophage metabolism, polarization, and inflammatory activation are closely intertwined. The proinflammatory M1 macrophages are highly glycolytic whereas anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages utilize oxidative phosphorylation as their main source of energy. Classical (M1) activation with microbial stimuli and IFN-γ enhances glycolysis, thereby fuelling the macrophages with fast energy and biosynthetic precursors for the rapid killing of microbes and driving their inflammatory response. With aging, in macrophages, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, increases due to misfolded proteins, decreased unfolded protein response capacity and decreased autophagy. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction leads to reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and increased cytosolic calcium levels which in turn activate NLRP3 inflammasomes, leading to mature IL-1β protein. Activation of macrophages by LPS or hypoxia enhances glycolysis and ROS production. In M2-polarized macrophages, AMPK and SIRT1 activate PGC-1, driving M2 polarization, while simultaneously promoting mitochondrial function. AMPK and SIRT1 also inhibit HIF-1α and NF-kB, thereby inhibiting M1 polarization [13].

Metabolic regulation of inflammasome activation

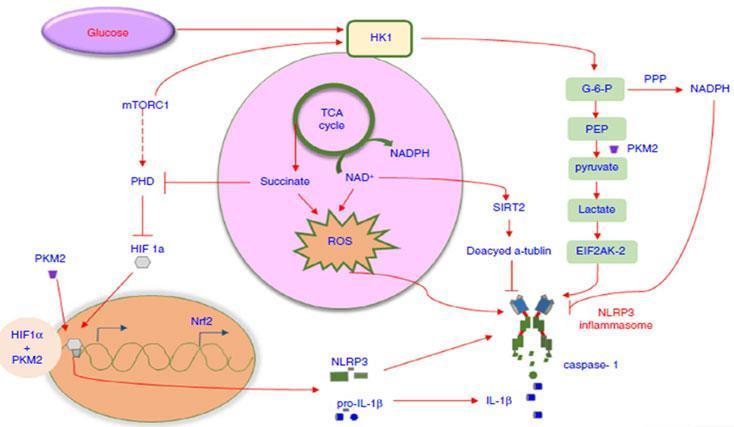

- Inflammasome activation in macrophages is also interlinked with the metabolic pathways of energy generation. As shown in Figure 1, the inhibition of mTORC1 decreased the expression of hexokinase, thus suppressing the NLRP3 inflammasome response, suggesting that mTORC1/HK1-dependent glycolysis axis is involved in inducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation but not AIM2 inflammasome activation. In addition, glucose deprivation and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) treatment can suppress caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion[14]. Pyruvate kinase M2 a glycolytic enzyme strongly induces phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2 (EIF2AK2). The activated EIF2AK2 can promote the activation of the NLRP3 or AIM2 inflammasome in LPS-activated bone marrow-derived macrophages.

- Succinate, an intermediate accumulated in the TCA cycle in LPS-stimulated microphages, lead to HIF1-α stabilization which cause NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Itaconate, one of the most highly induced metabolites in activated macrophages, inhibits the succinate dehydrogenase-mediated oxidation of succinate. Through this action itaconate modulate the expression of several LPS-regulated genes involved in inflammasome activation and function including Il1b, Il18, P2rx7, Casp1, and Pycard etc. In addition, Irg1-/- (gene expressing itaconate) bone marrow derived macrophages also sustained higher expression of mature IL-1b and IL-18 under conditions that stimulate NLPR3[15]. This highlight itaconate as a major physiological regulator of the global metabolic rewiring and effector functions of inflammatory macrophage.

- Fatty acid synthesis mediated by fatty acid synthase which is activated in LPS stimulated macrophages, which promotes NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β transcription by activating the AKT/p38 MAPK signalling axis. The generation of long-chain saturated fatty acids also act as critical mediators for inflammasome activation. It is reported that fatty acid oxidation potentiates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a NOX4-dependent pathway with no effect on NLRC4, NLRP1 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. This suggests that fatty acid synthesis is critical for initiating NLRP3 inflammasome activation and that fatty acid oxidation acts as a positive regulator during downstream cascade amplification [16].

- Activated inflammasomes also control cellular metabolism. NLRP3 inflammasome activation is correlated with GAPDH proteolysis in mouse skeletal muscle during ageing. It is reported that adipose tissue macrophages regulate the age related reduction in adipocyte lipolysis in mice by lowering the bioavailability of noradrenaline. It was shown that ageing upregulates genes that control catecholamine degradation in an NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent manner. Deletion of NLRP3 in ageing restored catecholamine-induced lipolysis by downregulating growth differentiation factor-3 (GDF3) and monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) that is known to degrade noradrenaline [17].

- Macrophages, as major initiators, effectors, and regulators of inflammatory responses, are central player in the systemic condition of inflammaging. The macrophage metabolism is tightly intertwined with the polarization and inflammatory activation. Targeting specific metabolic pathways in macrophages to induce repolarization and thereby modulating inflammatory responses warrants further study in the context of aging.