Adjuvants: basic concepts, mechanisms of action and importance for vaccine formulation

- Key elements of effective vaccines include the immunogen(s), against which adaptive immune responses are specifically elicited; immune potentiators or adjuvants to stimulate the innate immune system which subsequently activates the specific adaptive immune response; delivery systems to ensure that the vaccine is delivered to the right place at the right time, and a protocol of administration to generate protective immunological memory.

- However, since the delivery system may also present adjuvant properties, a clear separation between them (delivery system and adjuvant immune potentiators) is not always possible depending on the vaccine formulation.

- Adjuvants are therefore substances when in combinantion with an antigen evokes an enhanced immune response against the antigen when compared with the response against the antigen alone (humoral or cellular mediated immune response). The formulation and development of vaccines based on the use of recombinant proteins has been the focus of the vaccine industry in the last decades.

- This type of immunogen presents weak or poor immunogenicity when given alone, and thereby require the use of adjuvants to elicit a protective and long-lasting immune response. The successful use of recombinant proteins as vaccines for humans, including hepatitis B and HPV, was possible due to the use adjuvants. The development of novel adjuvants is an extremely important field in vaccinology.

- Examples of immunogens: 1) whole inactivated or attenuated organisms (can be a mixture of various strains); 2) isolated and purified proteins, glycoprotein or carbohydrates; 3) recombinant proteins and glycoproteins; 4) peptides, etc.

- Examples of adjuvants and delivery systems: 1) Bacterial products; 2) Toxins and lipids; 3) Nucleic acids; 4) Proteins; 5) Peptidoglycans; 6) Carbohydrates, Peptides; 7) Cytokines; 8) Small molecules; 9) Mineral salts; 10) surface active agents; 11) Synthetic micro- or nano-particles; 12) Oil-in-water emulsions; 13) Liposomes; 14) Attenuated bacteria, etc.

Mechanisms of action of adjuvants

- The main function of an adjuvant is to potentiate a specific, strong and long-lasting protective immune response to the immunogen. These functions can be accomplished by a unique molecule or in combination with a carrier or delivery system.

- The main properties of an adjuvant are a) boosting the immune response against the targeted immunogen (through activation of innate immunity), and b) inducing a longer-lasting immune protection (by depot or dosification of the immunogen),thus minimizing the amount of the administered immunogen and increasing the efficiency of the immunointervention procedure.

- Additional properties may be as immunomodulator (modifies the immune response to achieve the appropriate protective immunity, either as an activator or tolerizing molecule) and stabilizer of the immunogen.

- There is also concern regarding potential harmful adverse effects of vaccine- containing adjuvants due to the pro-inflammatory properties of adjuvants as immune stimulator, or the possibility to trigger responses to self-proteins when administered in combination. A rational selection and optimization of biological substances should be followed for registration and approval of novel adjuvants for human use;

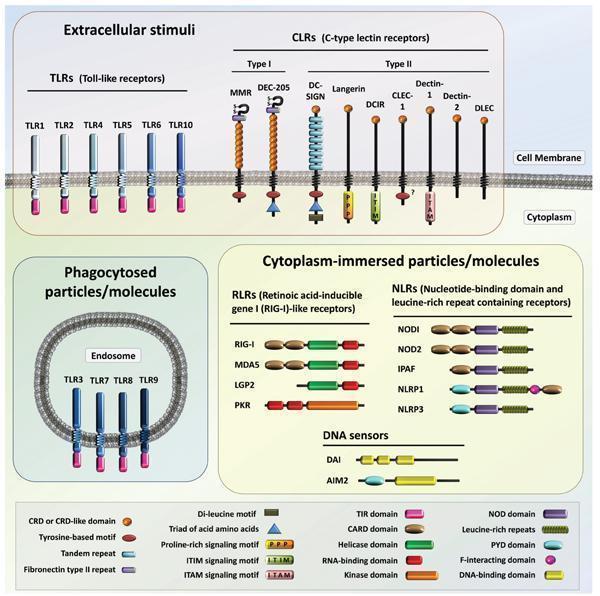

- During an infection, the organism sense the presence of a pathogen through the presence of MAMPs (Microorganism-associated molecular patterns) by PRRs (Pattern recognition receptors). PRRs can be found in the membrane (CLRs, C-type Lectin Receptors; TLRs, Toll–like Receptors), in endosomes (TLRs), cytoplasm (RLRs, Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) – like Receptors; NLRs, Nucleotide-binding domains and Leucine-rich repeat containing Receptors; several DNA sensors) or they can be released as soluble molecules (TLRs) (Figure 1).

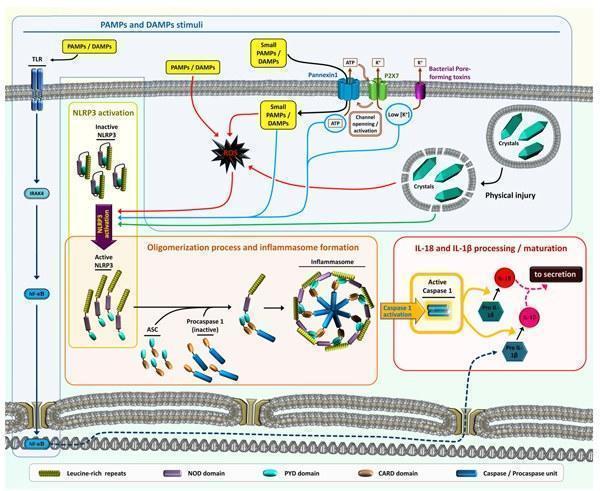

- Cell death and damage during (or not) an infection will provide danger signals (DAMPs – Danger-associated molecular patterns and PAMPs – Pathogen-associated molecular patterns) that are also recognized by the organisms through PRRs, which are part of the inflammasome system.

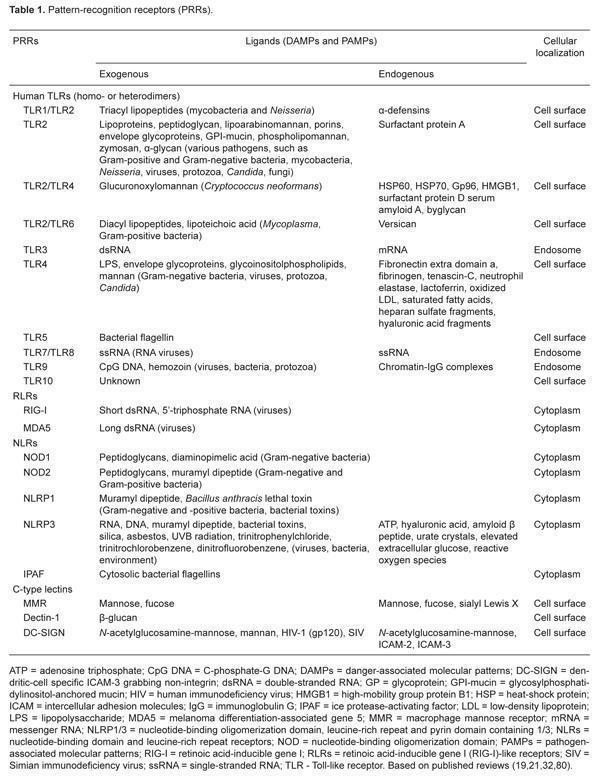

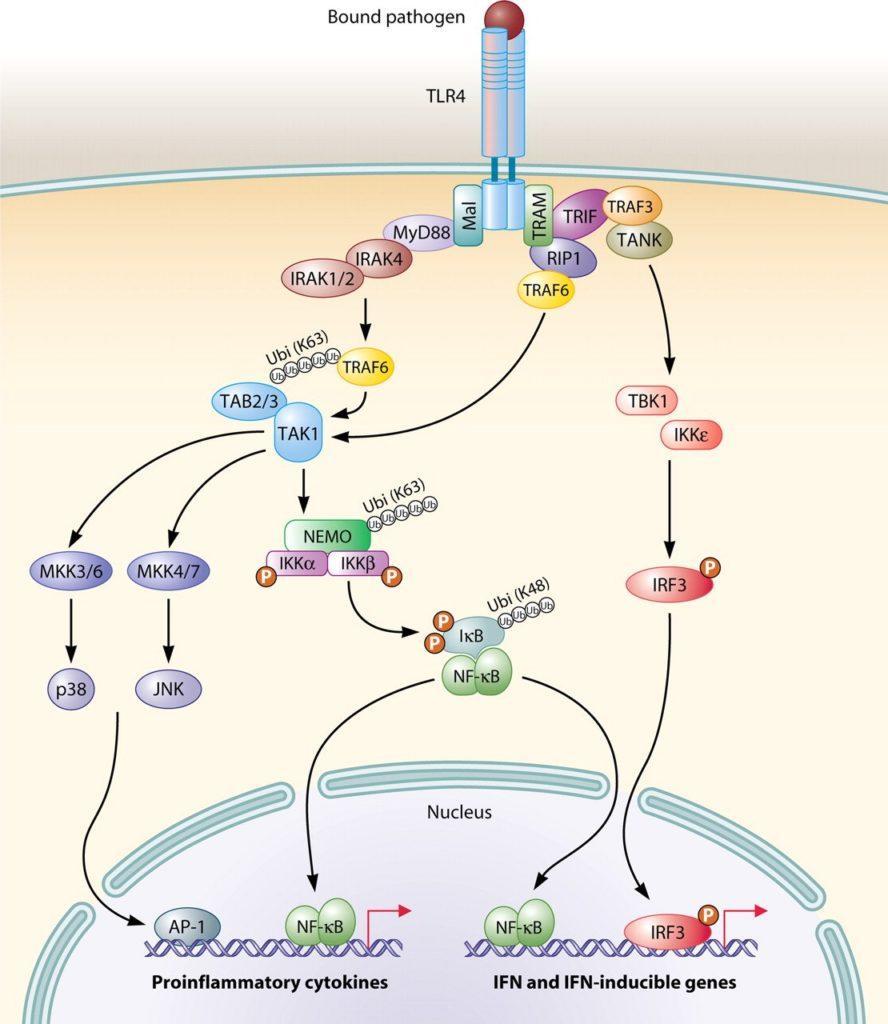

- PRRs ligands can be of endogenous or exogenous origin (Table 1).

- DAMPs and PAMPs ligands bind to specific PRRs and during an infection, multiple PAMPs and DAMPs are presented to cellular PRRs (Figure 2), eliciting a complex downstream responses (signal transduction pathways activations, gene expression or suppression, pro-cytokine processing and secretions).

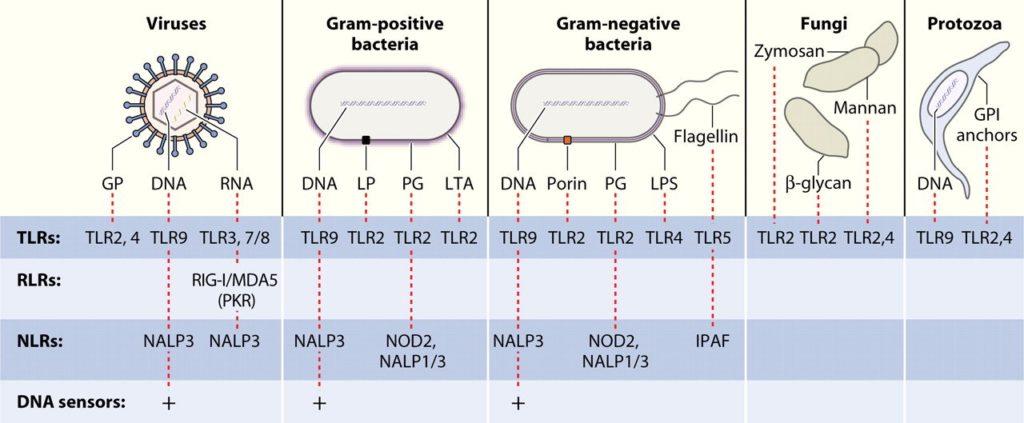

- During the activation of a specific PRR, the signal is transduced to the nucleus with the induction of transcription of specific genes, related to pro-inflammatory and interferon related responses (Figure 3, an example illustrated by TLR4 activation) or;

- There is a strong cross-talk and complementary responses among the different pathways involved in the PRRs activations and responses. For instance, activation of TLR4 response will induce the expression of pro-Interleukin 1β (pro-IL-1β) mRNA as well as the protein translation. On the other hand, the activation of specific NLRs will activate the formation of a complex named inflammasome that will lead to caspase 1 activation, resulting in the processing of pro-IL-1β to mature IL-1β to be secreted by the cell along with IL-18 (Figure 4).

- Attenuated organisms (used as vaccine) mimic a natural infection, present a complexity of PAMPs (in time and place) and they do not need adjuvants in the vaccine formulations.

- When a host cell is contacted by the pathogen, membrane PRRs are bound and cells become activated. Therefore, PRRs mediate cell activation and some of them may additionally mediate internalization of the microorganism, with the subsequent capacity to engage intracellular PRRs.

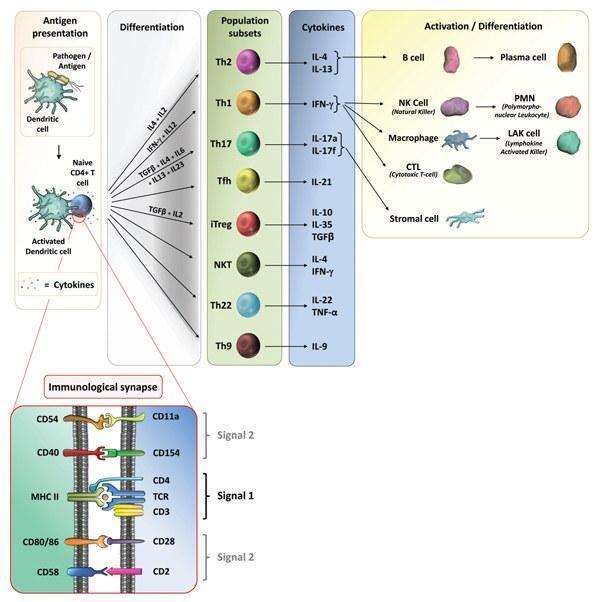

- Depending on the cellular compartment where the microorganism is allocated, antigens are processed and presented to T cells in the context of the major histocompatibility complex molecules (MHC): class II to CD4+ T-helper lymphocytes or class I to CD8+ T cells (Iwasaki A and Medzhitov R, 2010).

- Depending on the interaction of the antigen presenting cell with the T cell, and the context of antigen presentation (MHC class I or II-signal 1 of T cell activation), will be the shape of the adaptive immune response induced. The expression of specific co-stimulatory molecules (signal 2 of T cell activation) and secretion of cytokines (signal 3 of T cell activation) imprints the differentiation signature of T cells (Figure 5). The adjuvant molecule mainly modulates signals 2 and 3.

- The presence of complex MAMPs, PAMPs and DAMPs in time and place will define the innate mechanism triggered and the type of inflammation that will promote the adaptive immune response specific for a pathogen.

- The protective immune response is the result of the activation and interaction of the innate and adaptative immune systems. The characterization of the innate agonists, and the intracellular pathway induced, will shed light to define novel molecules that could be exploited as adjuvants. Therefore, DAMPs, MAMPs, PAMPs, and their combination, can be considered potential vaccine adjuvants, and provides a toolbox for a more rational design of novel adjuvants (O’Hagan DT, Fox CB, 2015). It is important to notice that some DAMPs, MAPMs and PAMPs may provide some undesirable pro-inflammatory responses, as it was mentioned before.

- As an example, LPS binds to TLR4 and triggers both Myd88-dependant and independant pathways promoting the activation of the innate cell (Figure 3). However, LPS can be hydrolysed to Monophosphoryl Lipid A (MPLA), or even synthetic MPLA-like molecules can be developed, and it maintain its ability to bind TLR4 with stimulation capacity only of the Myd88-independant pathway, avoiding the expression of undesirable pro-inflammatory genes (Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock DT, 2007; Reed SG et al, 2016).

Development of novel adjuvants

- Adjuvant development comprises the combination of DAMPs, MAMPs and PAMPs, the development of fusion proteins with self-adjuvant properties (Moyle PM, 2017), particulate formulations such as liposome, Virus-like particles (VLPs), virosomes, protein assemblies, Immune-Stimulating Complexes (ISCOMs), nanoparticles and bacterial ghosts (Alving CR et al, 2016; Karch CP, Burkhard P, 2016, Hajam IA et al, 2017; Bonam SR et al, 2017; Saxena M, Bhardwaj N, 2017), the combination with synthetic CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (Bonam SR et al, 2017), with cytokines, with polimers, saponins (Burakova Y et al, 2017) and many others possibilities (Cimica V, Galarza JM, 2017).

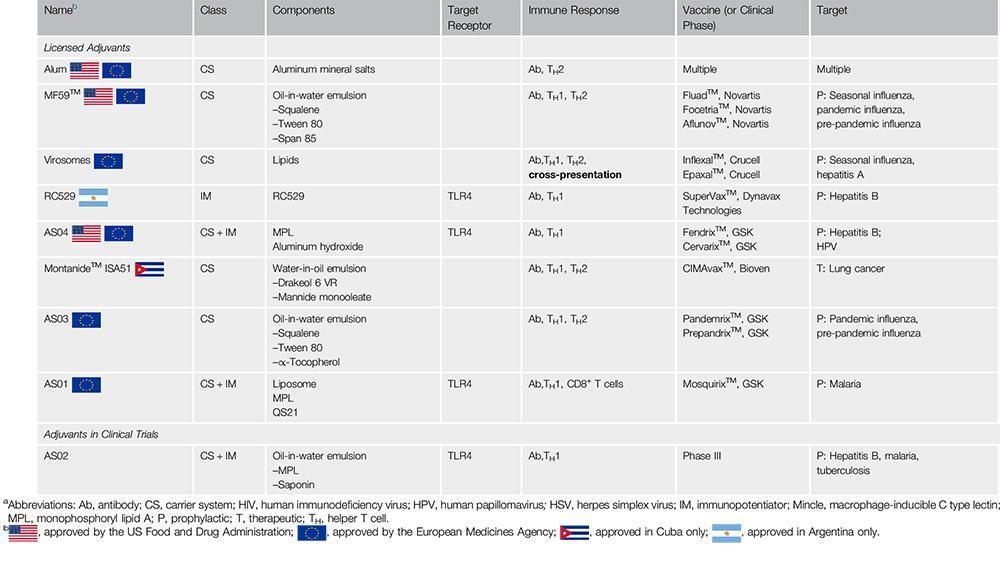

- Alum salts were the first adjuvant used in current human vaccines and the mechanisms of actions is still not completely understood. It may involve antigen depot, activation of inflammasome, interaction with dendritic cell membrane lipids and/or host DNA interaction. Oil in water MF59 adjuvant is used in one influenza vaccine and ATP seems to mediate its adjuvant response.

- Adjuvant systems (AS) were also developed by GSK (Garçon N, Di Pasquale A, 2017) and are combinations of immunostimulatory molecules that are designed to allow vaccines to provide better and broader protection than classical formulations containing only alum. For instance, MPLA included in HPV (Cervarix) and Hepatitis B (Fendrix) is combined with alum to compose the AS04.

- It is predicted that the list of clinically approved adjuvant will increase over the next years (Table 2).

Quiz

Download the Presentations for this section:

Download Relevant Resources for this section:

References:

- Mogensen TH (2009) Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev, 22(2):240-73.

- Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R (2010) Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science,327(5963):291-5.

- Dowling JK and Mansell A (2016) Toll-like receptors: the swiss army knife of immunity and vaccine development. Clin Transl Immunology, 5(5):e85.

- Moyle PM (2017) Biotechnology approaches to produce potent, self-adjuvanting antigen-adjuvant fusion protein subunit vaccines. Biotechnol Adv., 35(3):375-389.

- Alving CR, Beck Z, Matyas GR, Rao M (2016) Liposomal adjuvants for human vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Deliv., 13(6):807-16.

- Karch CP, Burkhard P (2016) Vaccine technologies: From whole organisms to rationally designed protein assemblies. Biochem Pharmacol., 120:1-14.

- Garçon N, Di Pasquale A (2017) From discovery to licensure, the Adjuvant System story. Hum Vaccin Immunother.,13(1):19-33.

- Hajam IA, Dar PA, Won G, Lee JH (2017) Bacterial ghosts as adjuvants: mechanisms and potential. Vet Res., 48(1):37.

- Gutjahr A, Tiraby G, Perouzel E, Verrier B, Paul S (2016) Triggering Intracellular Receptors for Vaccine Adjuvantation. Trends Immunol., 37(9):573-87.

- Reed SG, Hsu FC, Carter D, Orr MT (2016) The science of vaccine adjuvants: advances in TLR4 ligand adjuvants. Curr Opin Immunol., 41:85-90.

- Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock DT (2007) Immunology. The shape of things to come. Science, 316(5831):1574-6.

- Bonam SR, Partidos CD, Halmuthur SKM, Muller S (2017) An Overview of Novel Adjuvants Designed for Improving Vaccine Efficacy. Trends Pharmacol Sci., 38(9):771-793.

- O’Hagan DT, Fox CB (2015) New generation adjuvants–from empiricism to rational design. Vaccine, 33 Suppl 2:B14-20.

- Saxena M, Bhardwaj N (2017)Turbocharging vaccines: emerging adjuvants for dendritic cell based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol., 47:35-43.

- Burakova Y, Madera R, McVey S, Schlup JR, Shi J (2017) Adjuvants for Animal Vaccines. Viral Immunol., 2017 Jun 15. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0049. [Epub ahead of print]

- Cimica V, Galarza JM (2017) Adjuvant formulations for virus-like particle (VLP) based vaccines. Clin Immunol., 183:99-108.

- Mascarenhas DP, Zamboni DS (2017) Inflammasome biology taught by Legionella pneumophila. J Leukoc Biol., 101(4):841-849.

- Miyaji EN, Carvalho E, Oliveira ML, Raw I, Ho PL (2011) Trends in adjuvant development for vaccines: DAMPs and PAMPs as potential new adjuvants. Braz J Med Biol Res., 44(6):500-13.