Leishmania introduction

Human leishmaniasis

The leishmaniases are a group of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), caused by protozoan Leishmania parasites. There is an estimated 350 million people in 98 countries who are at risk of leishmaniasis1. In 2013, the disease burden was estimated to be around 4 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)1, causing an estimated 63,500 deaths. As well as human disease, leishmaniasis also causes veterinary diseases in companion and other animals2.

A striking feature of these diseases is the ability of a single group of parasites – the genus Leishmania – to cause a spectrum of different diseases in human infections. Presentations of leishmaniasis include asymptomatic infections, a range of dermatological symptoms (cutaneous leishmaniasis or CL) and infections that disseminate to internal organs such as the liver, bone marrow and spleen (visceral leishmaniasis or VL), which are generally fatal in the absence of adequate, effective chemotherapy. One critical factor in the different presentations of leishmaniasis is clearly the parasite, as different presentations are generally associated with different species of Leishmania (Table 1).

[table id=186 /]

Table 1. Leishmania species

Different forms of leishmaniasis

Old world localized CL: Usually, lesions will start as a papule or nodule and grow, a crust develops centrally, that may fall off and expose an ulcer; the lesions will heal gradually over months or years. There are a wide variety of clinical presentations.

Old world ML: lesions may develop in the mouth or nose. This form of leishmaniasis does not heal spontaneously.

Old world diffuse CL (DCL): is characterised by widely disseminated cutaneous lesions that do not ulcerate. This form of leishmaniasis does not heal spontaneously.

Old world VL: Most infections are asymptomatic, but some individuals may develop symptomatic VL, that is characterised by fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia and weight loss. Symptomatic VL is fatal if left untreated.

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL): occurs in areas endemic for L. donovani. It appears after apparent cure of VL. It is characterised by macular, papular, or nodular lesions on the skin in which Leishmania parasites may be seen.

New world localized CL: is clinically and pathologically similar to old world form.

New world MCL: lesions may develop in the mouth or nose or on the genital mucosa and may disseminate to the upper respiratory tract. This form of leishmaniasis does not heal spontaneously.

New world diffuse CL (DCL): is clinically and pathologically similar to old world form.

New world VL: is clinically and pathologically similar to old world form.

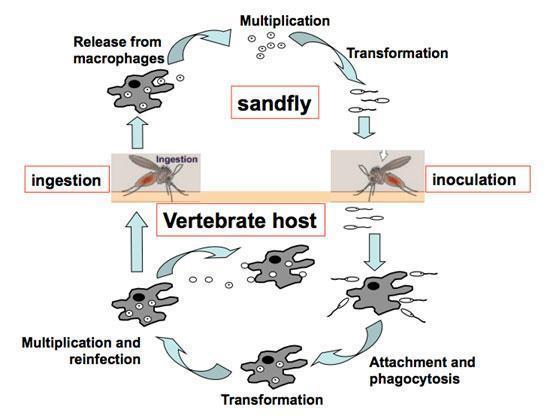

Life Cycle of Leishmania parasites

Life cycle in the mammalian host – who.int/tdr/publications/documents/leishmaniasis-life-cycle.swf

Life cycle in the sandfly – who.int/tdr/publications/documents/leish-sandfly.swf

Leishmania

- Protozoan parasites

- >20 Leishmania species are pathogenic for humans

- 2 stage life cycle

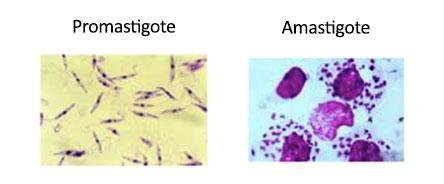

- Promastigote – in sandfly vector, mobile, flagellated

- Amastigote – in infected mammals, intracellular, resorbed flagellum, ovoid, 2-6mm, central nucleus

Immunity to Leishmania3,4

1. Experimental CL

Host cells:

- Neutrophils: See Section 3 – Neutrophils

- Macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells: Although Leishmania parasites can be found in neutrophils, they mostly replicate and survive in mononuclear phagocytes.

- Following injection of parasites in the skin, resident dermal dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages become rapidly infected; the fate of these infected macrophages and dendritic cells is unclear, it is still not known whether they migrate to the lymph nodes.

- Monocytes are recruited to the site of inflammation following injection of parasites in the skin and it seems that many of these monocytes become monocytes-derived DCs (moDCs). These cells have opposing roles: They can either promote the development of lesions by being permissive to parasite growth and by facilitating further monocyte recruitment; or upregulate MHCII presentation which is critical for the ability of DCs to act as antigen presenting cells (APCs).

- Stromal cells: persisting parasites can be found in fibroblasts forming the reticular meshwork of the lymph nodes

Adaptive Immunity

It has been well established that subcutaneous infection of mice with L. major parasites results in different outcomes depending on the strains of mice used: the majority of inbred strains of mice develop small lesions that heal spontaneously over a few weeks, these mice can control the replication of parasites; in contrast, BALB/c mice develop progressive nonhealing lesions and cannot control parasite replication. This experimental model of Leishmania major infection exemplifies the Th1/Th2 paradigm of resistance/susceptibility to intracellular infection and establishes that the archetypal Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 counter regulate a protective Th1 response and promote susceptibility to infection.

CD4+ T cells: It is generally accepted that a Th1 type immune response is associated with healing and a Th2 type response with nonhealing. CD4+ Th1 cells are critical for the control of Leishmania infection, as they make IFN-γ that activates macrophages to kill the intracellular parasites. Production of IFN-γ results in the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS); the latter catabolizes L-arginine into nitric oxide, which is toxic for Leishmania parasites. moDCs are particularly important for the induction of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th1 cells.

- CD4+ Th2 cells on the other hand are characterised by the production of cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13. These cytokines signal via the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) α chain and both can activate macrophages to upregulate arginase; this enzyme catabolizes L-arginine into polyamines (spermine, spermidine and putrescine) that promote parasite growth.

However, it is important to note that both IL-4 and IL-13 dependent and independent factors determine the outcome of experimental L. major infections5.

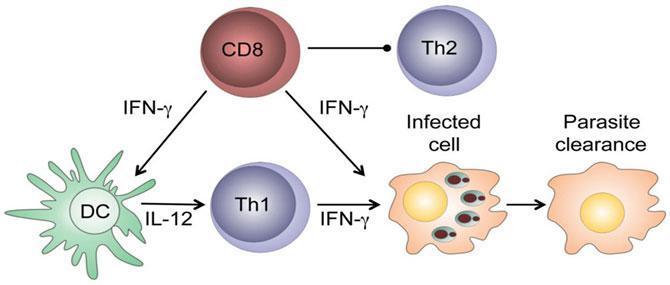

CD8+ T cells6

CD8+ T cells are activated during Leishmania infections. However, Leishmania antigens are not generated via the classical endogenous antigen presentation pathway and since there are no well characterized parasite-derived CD8+ T cell epitopes available, it is currently not known how leishmanial peptides are loaded onto MHC class I molecules and how priming of CD8+ T cells occurs in leishmaniasis.

The impact of CD8+ T cells on disease development depends on their effector function: CD8+ T cells contribute to healing of primary L. major infections or can increase pathology when they are cytolytic. The different effector functions depend on the Leishmania species, the inbred mouse strain used for infection and their location in the infected host.

i) Beneficial effector functions of CD8+ T cells:

CD8+ T cells have a protective role in low-dose leishmanial infections: they produce IFN-γ in the draining lymph nodes that can:

- activate parasitized macrophages to kill the intracellular parasites.

- enhance secretion of IL-12 that promotes the development of CD4+ Th1 cells that can block the development of Th2 cells.

After healing of primary infection, IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells contribute to protection against reinfection, are able to transfer delayed type hypersensitivity to recipient mice and are essential in vaccine-induced immunity.

ii) Detrimental effector functions of CD8+ T cells:

The cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells in lesions correlates with disease severity as evidenced by the higher expression of cytolytic markers in the skin lesions of infected susceptible mice as compared to resistant mice.

Th17 cells are a subset of activated CD4+ T cells acting as a bridge between adaptive and innate immunity where they promote neutrophil activation, immunity to pathogens and inflammation. In experimental CL, IL-17 has been shown to promote the progression of disease in mice genetically susceptible to L. major infection.

B cells

Mice infected with Leishmania parasites have high levels of parasite-specific IgG. However the role of B cells in experimental CL is controversial, some experiments suggest that B cells can contribute to the control of parasite replication, while other studies show that B cells do not play a role in lesion development or healing. A population of regulatory B cells has been described that was shown to contribute to the development of Th2 cells via the production of IL-107.

Parasite persistence

Despite the efficient control of lesion pathology and parasite replication by protective immune responses, a small number of parasites persists. IL-10 has been shown to play a major role in parasite persistence, by suppressing the immune response and thereby allowing for some parasites to survive. IL-10 can be produced by a variety of cells: regulatory T cells (Treg), Th1 cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells, DCs, macrophages and neutrophils and it is not yet clear which of these IL-10-producing cells contribute the most to the suppression of immune responses leading to parasite survival.

2. Experimental VL8-10

Most experimental studies of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in mouse are based on intravenous injection of large doses of amastigotes, thereby bypassing the early events in the skin and the migration of the parasites to the viscera. L. donovani or L. infantum infect the spleen, liver and bone marrow, however, the parasites only establish chronic infection in the spleen and bone marrow, infection in the mouse liver is self-resolving.

Host cells:

- In the liver, resident Kupffer cells harbor most parasites, these cells have a reduced ability to kill intracellular parasites, however, after a few weeks, the formation of granulomas and the production of inflammatory cytokines result in efficient activation of the Kupffer cells and killing of the parasites in the liver.

- In the spleen, Leishmania are preferentially taken up by specialized resident tissue macrophages. In contrast to experimental CL infections, moDCs are less efficiently infected.

Adaptive Immunity

Liver: The control of parasite replication in the liver relies on a Th1-dominated granulomatous response, characterised by the production of IFN-γ, induced by DC-derived IL-12.

Spleen: A few hours after infection, mature DCs will appear in T cell areas and produce IL-12. Activated CD4+ T cells appear in the first day after infection and this pool will increase and contribute to splenomegaly. DCs can also produce IL23p19 that can pair with IL-12p40 to form IL-23. The latter, in combination with IL-6, IL-1β or TGFβ can promote the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Th17; these cells play a protective role in experimental VL.

Loss of splenic lymphoid architecture

A structural change in the spleen is evident a few weeks post infection and coincides with the start of the chronic phase. This is mainly mediated by TNF-α that appears to result in the disorganization of periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths and in the loss of specialized macrophage populations. In addition, a loss of follicular dendritic cells is observed during the chronic phase of VL, resulting in the loss of germinal centers and B cell follicles, which are replaced by Leishmania-infected macrophages and plasma cells.

All in all, these structural changes disrupt cell-cell interactions that are crucial for the induction of an effective immune response.

CD8+T cells

CD8+ T cells play a crucial role for the control of primary infection and are the main mediators of immunity to reinfection. L. donovani can escape CD8+ T cell responses by several mechanisms: L. donovani can i) limit clonal expansion of CD8 + T cells; ii) induce CD8+ T cell exhaustion during the chronic phase of the disease, as shown by the inability of CD8+ T cells to produce IFN-γ, TNF, IL-2 and granzyme B; this exhaustion is paralleled by the upregulation of PD-1 (Programmed cell death protein 1) that plays a crucial role in the downregulation of immune responses. iii) In addition, effector CD8+ T cells appear to undergo a limited number of divisions and few of the cells that survive clonal contraction display an effector phenotype.

IL-10

IL-10 is one of the major factors driving disease progression in experimental leishmaniasis: IL-10-deficient mice are highly resistant to L. donovani infection. Several cells have been shown to produce IL-10, Treg, Th1 cells, NK cells, macrophages, B cells and DCs.

Considerations for experimental investigation of the pathogenesis of leishmaniasis11

To understand the host-parasite interactions and develop effective intervention strategies experimental animal models are widely used. To understand and evaluate results generated in experimental models the limitations and the influence of experimental parameters need to be considered. The outcome of experimental infection with Leishmania parasites is influenced by:

– Leishmania parasites:

- The Leishmania species used for experimental infections

- The virulence of the species

- Parasite inoculation: by needle or sand fly vector

- The life cycle stage of the parasites (promastigotes/amastigotes)

and the infectious stage of the infecting promastigotes (metacyclic/log-phase) - The route of infection (subcutaneous, intradermal, intravenous)

- The dose of the infectious inoculum

- The vector-transmitted compounds: saliva, promastigote-secretory gel

To study visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis, the main experimental parameters that need to be taken into account are:

- The genetic background of the infected host

- The immune response of the host

- The origin of the parasites (isolated from infected patients, dogs or rodents)

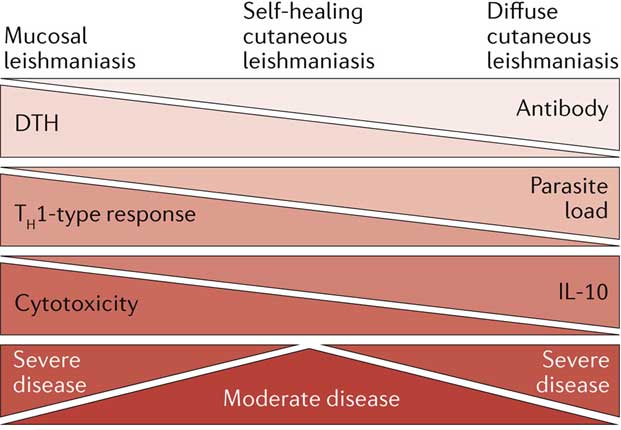

3. Human CL12

The type and magnitude of the immune response of humans are main contributors to the range of clinical manifestations of CL. The parasite dose, compounds transmitted during natural infection by the sand fly vector into the skin of humans and the presence of a double-stranded RNA-virus in some Leishmania species have also been shown to impact on the severity of human CL.

Healing CL: strong T cell response, high levels of IFN-γ, pronounced delayed type hypersensitivity responses (DTH), few parasites in lesions.

Diffuse CL: lack of DTH, inefficient immune responses, high antibody levels, unable to control parasite growth.

Mucosal CL: excessive Th1 responses, enhanced cytolytic CD8+ T cell responses, tissue destruction.

It is widely accepted now that the simplistic Th1/Th2 paradigm developed in experimental models of CL does not directly translate to the different clinical manifestations of human CL. Little is known about the mechanisms regulating healing or persistence of disease in CL patients. The majority of the work performed on human CL has been done with L. braziliensis and is summarized below.

Innate mechanisms of killing

Human monocytes can produce high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and can mediate ROS-dependent parasite killing; this mechanism can occur before the adaptive immune responses are established.

In contrast to experimental leishmaniasis, NO cannot be measured in human cells and the relative contribution of ROS and NO to the control of parasite growth in human leishmaniasis patients is not known.

CD4+ T cells:

CD4+Th1 cells: Th1 type responses are required to control infection with Leishmania parasites. However, high levels of the Th1-cytokine IFN-γ are present in patients with mucosal leishmaniasis and a combination of high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α is implicated in pathogenesis and lesion chronicity.

CD4+Th2 cells: Patients with severe CL do not have high levels of IL-4, indicating that Th2 cells are not as important for disease progression in humans than in experimental models.

CD4+Th17 cells: In CL patients the inflammatory response in the skin has been shown to correlate with IL-17 levels.

CD4+CD25+ T cells: CD4+CD25+ T cells with phenotypic and functional characteristics of regulatory T cells have been isolated from skin lesions of CL patients.

CD8+ T cells:

- CD8+ T cells from lesions do not express IFN-γ.

- CD8+ T cells isolated from skin lesions expressed markers of perforin and granzyme dependent cytotoxicity.

- CD8+ T cells expressed higher levels of granzyme A in L. braziliensis infected patients with large lesions.

- The expression levels of cytolytic markers was even higher in L. braziliensis patients with mucosal lesions.

- CD8+ T cells from lesions of L. braziliensis patients expressed high levels of CD107a, indicating that they degranulated in the lesions.

- Both parasite-specific CD8+ T cells and bystander CD8+ T cells are present in cutaneous lesions of patients infected with L. braziliensis.

- Transcriptome analysis of lesions from L. braziliensis patients showed that CD8+ T cells have a cytolytic phenotype and high expression of genes associated with the cytolytic pathway.

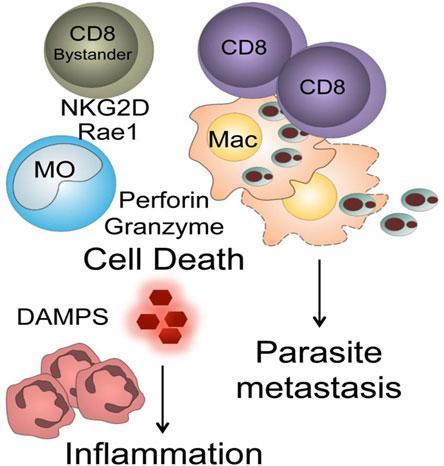

- CD8+ T cells have a pathogenic role in patients with severe cutaneous lesions due to L. braziliensis. A hypothetical model for L. braziliensis infection is shown below.

Parasite specific CD8+ T cells infiltrate the lesions, lyse parasitized cells resulting in the release of proinflammatory molecules, including some with damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS). Lysis of infected cells liberates parasites and this may promote increased metastasis. Leishmania infection results in upregulation of NKG2D ligands. If by-stander memory CD8+ T cells recruited into the lesions express NKG2D they can lyse target cells resulting in cell death and increased inflammation.

Whether CD8+ T cells have a detrimental role in human cutaneous leishmaniasis induced by Leishmania spp other than L. braziliensis remains to be determined.

Importantly, responses determined in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with CL do not necessarily reflect the responses in the skin lesions.

4. Human VL10,13-15

VL is caused by L. donovani in Africa and on the Indian sub-continental and by L. infantum/chagasi (Table 1) in the Mediterranean region, southwest and central Asia and South America. The outcome of infection depends on a combination of parasite, host and vector factors. Infections with L. donovani or L. infantum can result in subclinical or asymptomatic disease or into disseminated visceral disease, where the parasites infect cells of the reticuloendothelial system in various tissues, predominantly infiltrating the spleen, bone marrow, liver and lymph nodes. This stage of the disease is fatal if left untreated.

Immunosuppression in VL patients

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from individuals with subclinical or asymptomatic disease have the ability to respond to activation with Leishmania antigen and produce cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-12. These patients appear to be immune to reinfection. This is in sharp contrast with PBMCs from patients with symptomatic disease who have lost the ability to produce IFN-γ in response to antigenic stimulation and at late stages of the disease, to polyclonal activation. Active VL is therefore associated with a profound immunosuppression.

The recent use of a whole blood assay to assess the ability of whole blood cells to produce IFN-γ in response to polyclonal stimulation showed opposing results16,17. In India, IFN-γ was readily detected in patients with active VL, whereas similar experiments in Ethiopia showed that IFN-γ production was low or below detection limit in VL patients with active disease and was restored after treatment.

In Indian patients, CD4+ T cells were shown to be the main source of IFN-γ and in splenic aspirates, this CD4+ T cell-derived IFN-γ was shown to limit parasite replication.

T cell exhaustion

During active VL, CD8+ T cells exhibit functional impairment and increased expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4, that are indicative of anergy/exhaustion. Exhausted CD4+ T cell populations have been shown to a lesser extent in dogs, but not yet in human VL patients.

Inflammation

Symptomatic VL is not characterised by a Th1 or Th2 type response, with reports of both increase and decrease of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the plasma. One key feature of patients with active VL is the high plasma level of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, IP-10, TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-27 and C-reactive protein.

IL-10

Increased levels of plasma IL-10, a potent immunosuppressive cytokine, have consistently been associated with symptomatic VL, suggesting that IL-10 plays a crucial role in symptomatic VL. Indeed, ex vivo neutralisation of IL-10 in splenic aspirates from VL patients promoted parasite killing, by a mechanism that appear to involve increased production of TNF-α and IFN-γ by spleen cells. IL-10 can be produced by many cell types, including innate cells, B and T cells. In the spleen of VL patients, the major source of IL-10 has been identified as CD4+CD25–Foxp3– T cells.

Quiz

Download the Presentations for this section:

Download Relevant Resources for this section:

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Recent Developments in Diagnosis and Management

References

- DALYs, G. B. D. et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 386, 2145-2191, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X (2015).

- Palatnik-de-Sousa, C. B. & Day, M. J. One Health: the global challenge of epidemic and endemic leishmaniasis. Parasit Vectors 4, 197, doi:10.1186/1756-3305-4-197 (2011).

- Kaye, P. & Scott, P. Leishmaniasis: complexity at the host-pathogen interface. Nat Rev Microbiol 9, 604-615, doi:nrmicro2608 [pii] 10.1038/nrmicro2608 (2011).

- Mougneau, E., Bihl, F. & Glaichenhaus, N. Cell biology and immunology of Leishmania. Immunol Rev 240, 286-296, doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00983.x (2011).

- Hurdayal, R. & Brombacher, F. The role of IL-4 and IL-13 in cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Immunol Lett 161, 179-183, doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2013.12.022 (2014).

- Novais, F. O. & Scott, P. CD8+ T cells in cutaneous leishmaniasis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Semin Immunopathol 37, 251-259, doi:10.1007/s00281-015-0475-7 (2015).

- Ronet, C. et al. Regulatory B cells shape the development of Th2 immune responses in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major through IL-10 production. J Immunol 184, 886-894, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901114 (2010).

- Kaye, P. M. et al. The immunopathology of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Immunol Rev 201, 239-253, doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00188.x (2004).

- Rodrigues, V., Cordeiro-da-Silva, A., Laforge, M., Silvestre, R. & Estaquier, J. Regulation of immunity during visceral Leishmania infection. Parasit Vectors 9, 118, doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1412-x (2016).

- Stager, S., Joshi, T. & Bankoti, R. Immune evasive mechanisms contributing to persistent Leishmania donovani infection. Immunol Res 47, 14-24, doi:10.1007/s12026-009-8135-4 (2010).

- Loeuillet, C., Banuls, A. L. & Hide, M. Study of Leishmania pathogenesis in mice: experimental considerations. Parasit Vectors 9, 144, doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1413-9 (2016).

- Scott, P. & Novais, F. O. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: immune responses in protection and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 581-592, doi:10.1038/nri.2016.72 (2016).

- Nylen, S. & Sacks, D. Interleukin-10 and the pathogenesis of human visceral leishmaniasis. Trends Immunol 28, 378-384 (2007).

- van Griensven, J. & Diro, E. Visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 26, 309-322, doi:10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.005 (2012).

- Goto, H. & Prianti, M. G. Immunoactivation and immunopathogeny during active visceral leishmaniasis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 51, 241-246, doi:S0036-46652009000500002 [pii] (2009).

- Singh, O. P. et al. Reassessment of immune correlates in human visceral leishmaniasis as defined by cytokine release in whole blood. Clin Vaccine Immunol 19, 961-966, doi:10.1128/CVI.00143-12 (2012).

- Adem, E. et al. Successful Treatment of Human Visceral Leishmaniasis Restores Antigen-Specific IFN-gamma, but not IL-10 Production. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10, e0004468, doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004468 (2016).