SARS-CoV-2 origin and transmission

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) first identified in December 2019, is the etiological agent of coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

- SARS-CoV-2 has zoonotic origin, and shares genomic similarity with other zoonotic viruses responsible for SARS (SARS-CoV-1) and MERS (EMC/2012 coronavirus)

- Genomic analysis SARS-CoV-2 has demonstrated that the virus has a receptor binding domain in the spike (S) protein consisting of 6 amino acids which not only differentiates it from SARS-CoV-1 but also confers it with ability to bind human or human-like Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-1 (ACE2) with high affinity.

- SARS-CoV-2 also has a polybasic furin cleavage site on the highly variable spike protein which is also unique to SARS-CoV-2. This site allows cleavage by proteases and determines viral host range and is potentially associated with increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.

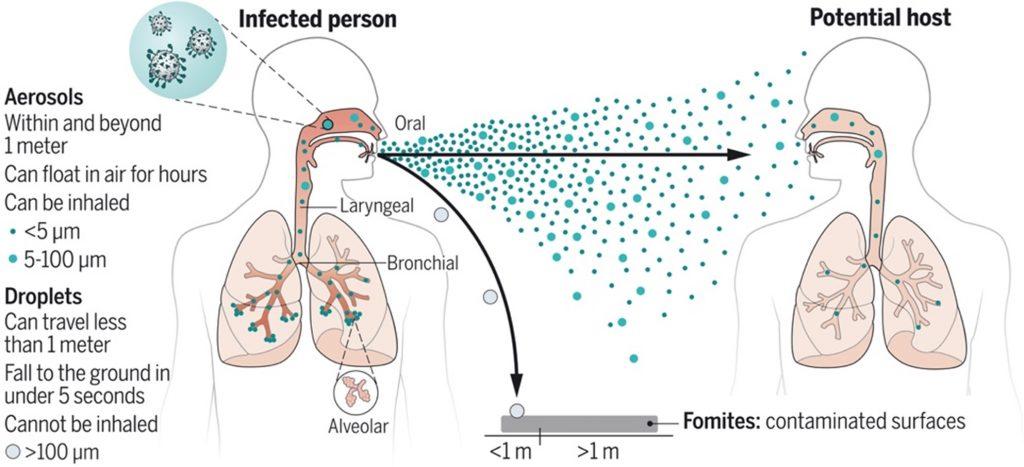

- SARS-CoV-2 is airborne, thus wearing a mask remains one of the most effective precautionary measures for preventing acquisition of the virus (Figure 1).

SARS-COV-2 Pathogenesis

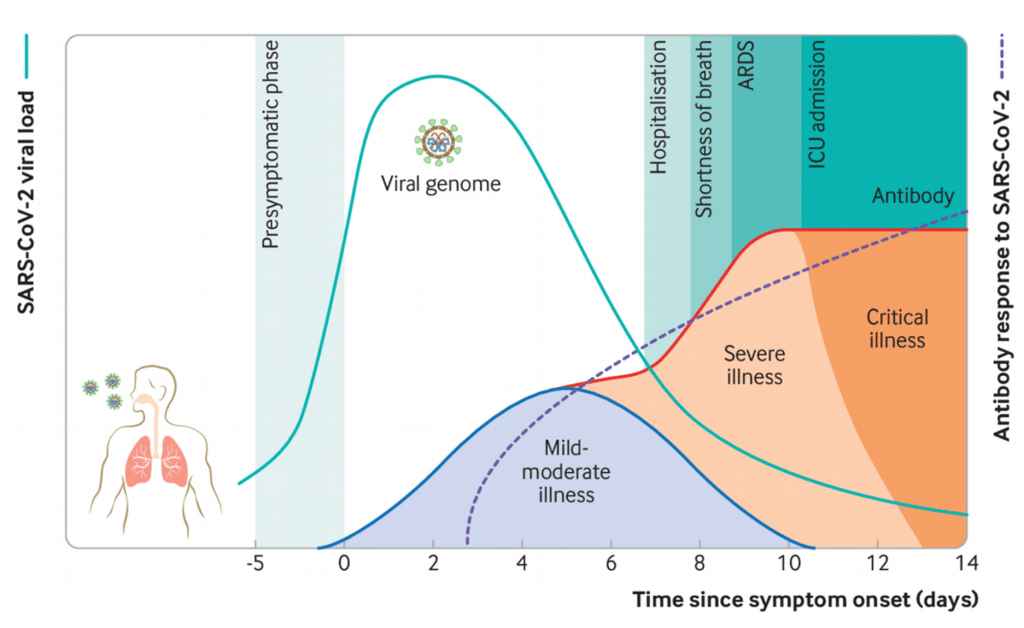

- SARS-CoV-2 causes a broad spectrum diseases ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe symptomatic disuses (Figure 2). Most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic or develop mild symptoms such as fever, cough, malaise, myalgia, headache, and taste and smell disturbance.

- Severe COVID-19 is associated with excessive innate immunity which results in pathology leading to more host cell and tissue damage even when viral load is low. Additionally, individuals with severe COVID-19 also develop additional complications such as thrombosis, sepsis and multi-organ dysfunction.

- Infection induces robust antibody (Ab) and T cell responses, which in most cases likely controls viremia before COVID-19 pathogenesis progressors.

- Studies have shown that although circulating SARS-CoV-2-specific Ab and T cell responses may wane quickly, natural infection (and potentially vaccination) induces long-lasting memory B cell immunity which persists despite a decline in circulating SARS-CoV-2-antibodies.

COVID-19 vaccines

- There have been multiple COVID-19 vaccines that have been tested in pre-clinical and clinical trial settings., some of which are highlighted in Table 1.

- By early 2021, mRNA-1273 (mRNA vaccine; Moderna), BNT162b2 (mRNA vaccine; Pfizer/BioNTech) and Sputnik V (viral vector; Gamaleya) demonstrated over 90% efficacy against acquisition of SARS-CoV-2, while other viral vector vaccines Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and AZD1222 (ChAdOx1; Oxford/Astra-Zeneca) vaccines didn’t perform as well with efficacies above 50% depending on the region, and as low as 20% for AZD1222 when tested in South Africa.

Table 1: COVID-19 vaccines

[table id=247 /]

Interested in learning more about COVID-19 vaccines and responses read the following news summaries:

- COV2.S is safe and immunogenic

- Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine

- BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy results

- Safety and immunogenicity of Sputnik V vaccine

- Viral genomic analysis of breakthrough infection in vaccinated individuals highlighted the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants (discussed in detail below) which significantly lowered efficacy signal of Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and AZD1222 (Oxford/Astra-Zeneca), while other vaccine mRNA-1273 (Moderna), BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) and Sputnik V (Gamaleya) were tested when the original SARS-CoV-2 variant was still the most prevalent.

- All vaccines have been shown to induce robust vaccine induced humoral and cellular immunity and are very efficacious against severe COVID-19 which may require hospitalization or even lead to mortality.

- Due to limited global access to COVID-19 vaccines, largely resulting in vaccine inequity in Asia and Africa. Researchers are investigating novel vaccination strategies, such as heterologous prime-boost strategies to facilitate mass COVID-19 vaccinations.

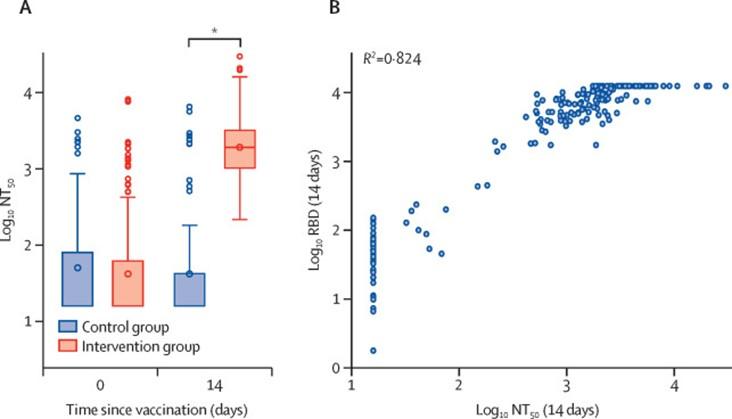

- Borobia et al., 2021, demonstrated that BNT162b2 given as a second dose in individuals vaccinated with AZD1222 (ChAdOx1-S) induced a robust immune response, with an acceptable and manageable reactogenicity profile. Additionally immune responses in the heterologous vaccination arm were detected as significantly higher levels that control vaccination arm (Figure 3)

Correlates of protection

- Due to limited knowledge of what protective immune responses are associated with prevention of COVID-19, majority of COVID-19 vaccines were tested without knowledge of a correlate protection of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- What is a correlate of protection? The immune responses that are statistically associated with protection against disease.

- Circulating antibodies and neutralizing antibodies are often considered potential correlates of protection against viruses, thus majority of natural SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity studies measure the induction of (neutralizing) antibodies (nAbs) as one of the trial endpoints. However, are Abs truly correlate of SARS-CoV-2 protection?

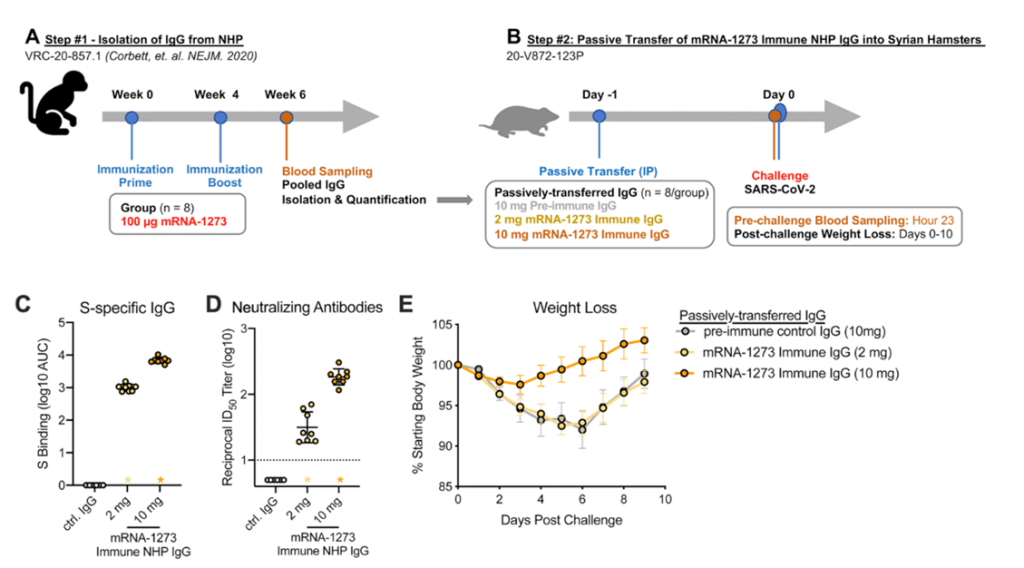

- Results from non-human primate models suggest mRNA-1273 vaccine induced Abs detectable in serum and localized at mucosal sites can restrict SARS-CoV-2 replication and confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection (Corbett et al., 2021). Further passive immunization of mRNA-1273 vaccine induced Abs mediated protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge in naïve hamsters (Figure 4).

- However, study in humans by Feng et al., demonstrated that though vaccination with AZD1222 induced robust levels of Abs including nAbs, Ab responses were not identified as a correlate of protection. However, vaccine induced humoral immune was associated with a lower risk of severe COVID-19.

Overall these results highlight the need for additional studies, as well as assessing investigating whether cellular immunity is a potential correlate of protection

SARS-CoV-2 Immune escape: Effect of SARS-CoV-2 variants on pre-existing immune responses

- Viruses are known to naturally mutate without impacting the ability of the virus to cause infection nor diseases. However, if mutations occur cumulatively in proteins that are required for viral entry or in epitopes targeted by immune responses this may impact transmissibility or diseases severity of the mutated virus.

- SARS-CoV-2 has evolved more rapidly than researchers anticipated, resulting in the evolution of multiple variants (viruses with unique multiple mutations that are distinct from the initial detected SARS-CoV-2 strain). These variants have been divided into variants of concern (VOC) and interests (VOI).

- As of 6th September 2021, there were 4 main VOC (Table 2) which are associated with mutations in the S protein which contribute to either increased transmissibility, increased pathogenicity, or both.

- Additionally, mutations in the VOCs contributes to lower Ab neutralisation capacity by nAbs induced naturally or by COVID-19 vaccines, as well hinders the provision of convalescent plasma as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

- Interestingly, immune responses induced by the Beta VOC conferred cross-reactive immunity against the Gamma VOC (Moyo-Gwete et al., 2021). The suggests that developing vaccines that included known mutations in the VOC may increase the efficacy of vaccines.

Table 2: SARS-CoV-2 Variants of interest

[table id=248 /]

Source: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

- Majority of our understanding of immune escape has focused on humoral immunity. However, not much is known whether VOC also escape cellular immunity.

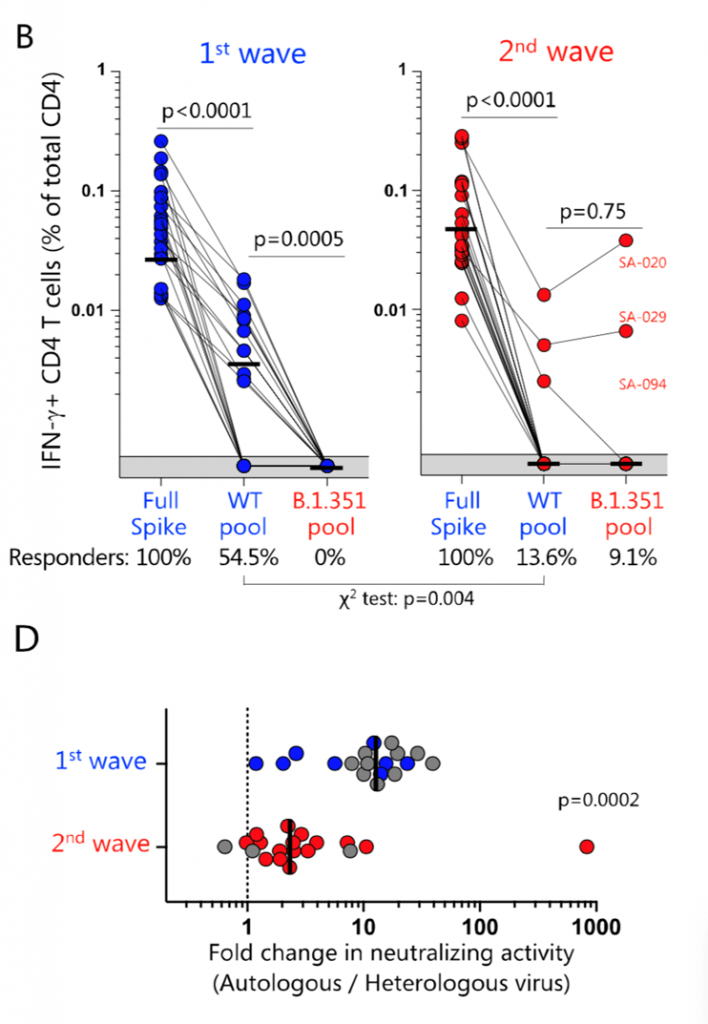

- Pre-print by Riou et al., shows that despite loss of recognition of immunodominant CD4 epitope(s) to the spike protein, which represented <20% of the total T cell responses, the overall CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to B.1.351 are preserved.

B.1.351 variant epitopes and neutralizing antibody responses. (B) Summary graphs of the frequency of IFN- -producing SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells in first wave (n = 22, left) and second wave (n = 22, right) COVID-19 patients. The proportion of patients exhibiting a detectable response to the different peptide pools (i.e., responders) is indicated at the bottom of each graph. (D) Fold-change in neutralization titres of plasma samples from COVID-19 patients recruited during the first wave (n = 18) or the second wave (n = 19) were tested for their neutralization cross-reactivity against the ancestral or B1.351 pseudoviruses. Bars represent medians. Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon test and the chi-squared test. [Source Riou et al, 2021]

Expand your knowledge

-

Understanding of Host-Pathogen Interaction & Applications (SARS-CoV-2)

-

Models for Testing Vaccines

-

Immune Responses to Vaccination

Quiz

Faculty Presentations:

Download these Resources (these will help you answer the questions):

References

- Altman et al., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants: Subversion of antibody response and predicted impact on T cell recognition. Cell Reports Medicine

- Andersen et al. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine

- Borobia et al.,. 2021. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 booster in ChAdOx1-S-primed participants (CombiVacS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet

- Dan et al., 2020. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science

- Feng et al., Pre-print. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv

- Gilbert et al., Pre-print. Immune Correlates Analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. MedRxiv

- Greenhalgh et al., 2021. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet

- Hartley et al., 2020. Rapid generation of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence. Science

- Madhi et al., 2021. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. NEJM

- Moyo-Gwete et al., 2021. Cross-Reactive Neutralizing Antibody Responses Elicited by SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 (B.1.351).NEJM

- Riou et al., 2021 (Pre-Print). Loss of recognition of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.351 variant spike epitopes but overall preservation of T cell immunity. medRxiv

- Singh & Yi. 2021. On the origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Experimental Molecule medicine.

- Tegally et al. 2021. Sixteen novel lineages of SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa. Nature Medicine

- Wang et al., 2021. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature

- Wibmer et al. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nature Medicine

- Vicek et al., 2020. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ

- Also read COVId-19 related articles on the Breaking News page

References

- Altman et al., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants: Subversion of antibody response and predicted impact on T cell recognition. Cell Reports Medicine

- Andersen et al. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine

- Borobia et al.,. 2021. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 booster in ChAdOx1-S-primed participants (CombiVacS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet

- Dan et al., 2020. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science

- Feng et al., Pre-print. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv

- Gilbert et al., Pre-print. Immune Correlates Analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. MedRxiv

- Greenhalgh et al., 2021. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet

- Hartley et al., 2020. Rapid generation of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence. Science

- Madhi et al., 2021. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. NEJM

- Moyo-Gwete et al., 2021. Cross-Reactive Neutralizing Antibody Responses Elicited by SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 (B.1.351).NEJM

- Riou et al., 2021 (Pre-Print). Loss of recognition of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.351 variant spike epitopes but overall preservation of T cell immunity. medRxiv

- Singh & Yi. 2021. On the origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Experimental Molecule medicine.

- Tegally et al. 2021. Sixteen novel lineages of SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa. Nature Medicine

- Wang et al., 2021. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature

- Wibmer et al. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nature Medicine

- Vicek et al., 2020. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ

- Also read COVId-19 related articles on the Breaking News page