Neutrophils in Innate Immunity

- Neutrophils are polymorphonuclear leukocytes and are the most abundant white blood cells, accounting for 50-70% of circulating leukocytes in human blood.

- Mature neutrophils are characterized by their segmented nuclei and cytosolic granules.

- Neutrophils develop from myeloid precursors in the bone marrow, after which they move into the blood. They circulate until they become activated, which results in extravasation and delivery to the site of infection.

- They are the predominant phagocytic and pathogen-killing cells in the first days of infection.

- Acute inflammation, characterized by influx of neutrophils into injured tissue, is one of the earliest events in an innate immune response.

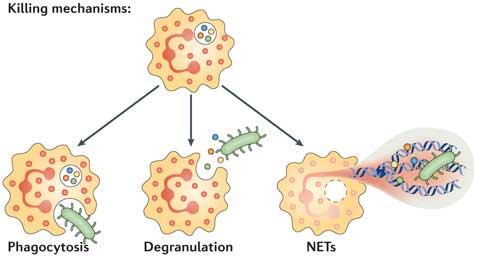

In tissues, neutrophils can promote the killing of pathogens by three main mechanisms:

- Phagocytosis: Neutrophils are able to detect and engulf pathogens. This can occur via opsonin-dependent mechanisms (by detection of antibodies or complement proteins bound to the pathogen) and opsonin-independent mechanisms (direct recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by neutrophil receptors). Pathogens become entrapped in a phagosome, and neutrophils kill them by producing reactive oxygen species and delivering antimicrobial proteins via granules (including lysozyme).

- Degranulation: Neutrophils possess a large number of granules that are delivered to the cell surface upon activation, fusing with the plasma membrane or that are delivered into phagosomes. These can be divided into four different types:

-

- Secretory vesicles – contain adhesion molecules that allow extravasation of neutrophils.

- Gelatinase granules – contain a matrix metallopeptidase (MMP9) that enables neutrophil migration.

- Azurophil granules – contain MPO that can kill pathogens, and elastases that disrupt bacterial outer membranes.

- Specific granules – contain lactoferrin that traps iron, required for bacterial growth, and also disrupts membranes.

- NETosis: Programmed death of neutrophils can result in the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

- Many microbial pathogens evolved to circumvent the attack of neutrophils through several protective mechanisms such as: (1) depressing the innate response, (2) interfering with their recognition, (3) inhibiting phagocytosis, (4) surviving intracellularly, (5) inducing the death of the neutrophil, and (6) evading killing by NETs.

Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs)

- NETs are considered to be part of innate immunity because they ensnare and may kill pathogens. Upon in-vitro activation a pathogen can induce NET formation. This can be mimicked using the pharmacological agent phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), IL-8, or LPS. Neutrophils release granule proteins associated with DNA to form an extracellular fibril matrix through an active process.

- Bacteria, some protozoan parasites and some pathogenic fungi induce neutrophils to form NETs. Thus, NETs disarm pathogens with antimicrobial proteins such as neutrophil elastase and histones that are bound to the DNA, providing for a high local concentration of antimicrobial components and can bind, inactivate, and even kill microbes extracellularly independent of phagocytic uptake.

- In addition to their antimicrobial properties, NETs may serve as a physical barrier that prevents further spread of pathogens.

- Furthermore, deposition of granule proteins of neutrophils into NETs may keep potentially injurious proteins like proteases from diffusing away and inducing damage in tissue adjacent to the site of inflammation.

- Paradoxically, NETs may also have a deleterious effect on the host because the exposure of extracellular histone complexes could potentially induce the development of autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematous (SLE). They can also trap but not kill the microorganisms, favoring its dissemination.

- NETs have also been identified in preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related inflammatory disorder in which neutrophils are known to be activated.

- These observations suggest that NETs play an important role not only in the protection but also in the pathogenesis of infectious and inflammatory disorders.

Neutrophils in Adaptive Immunity

- Neutrophils are classically considered as cells pivotal for the first line of defense in innate immunity. In recent years, evidence has accumulated that they are also important in the orchestration of adaptive immunity.

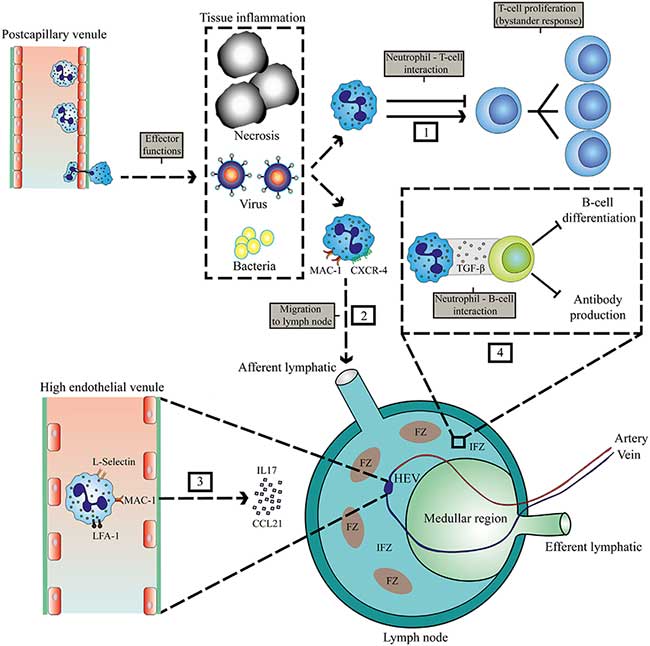

- Neutrophils rapidly migrate in high numbers to sites of inflammation and in some cases they can migrate to draining lymph nodes.

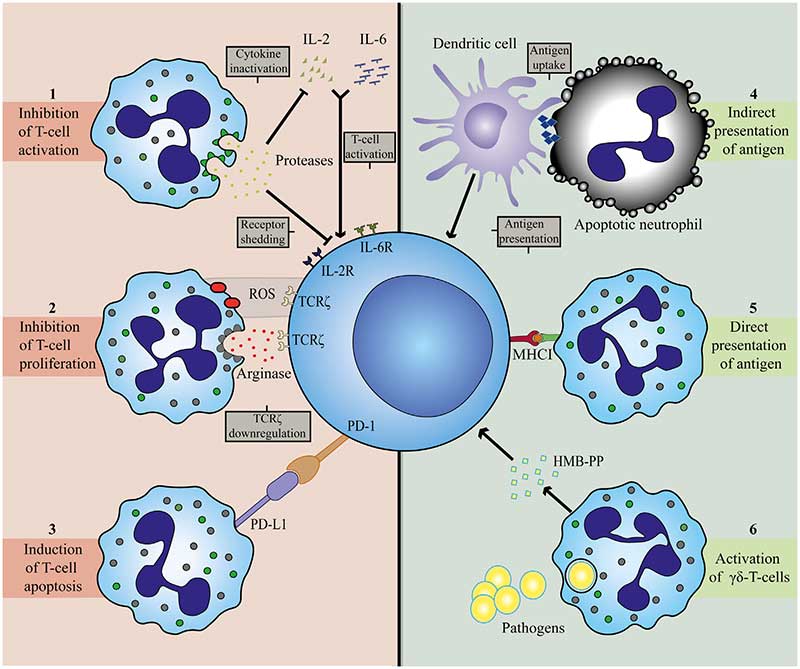

- At the site of inflammation as well as in selected cases in the lymph nodes, neutrophils can engage with lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells. This crosstalk occurs either directly via cell-to-cell contact, NETS or via mediators, such as proteases, cytokines, and radical oxygen species.

- Neutrophils are capable of modulating adaptive immune responses through interactions with T and B cells and antigen-presenting cells.

- Neutrophils may be found both in lymph nodes and spleen particularly under inflammatory conditions.

- There are two possible routes for neutrophils to enter lymph nodes, via blood vessels or via afferent lymphatics:

- 1) The first route requires exiting the circulation via high endothelial venules (HEVs). This mechanism is controversial, as human neutrophils seem to lack the expression of CCR7, a receptor for CCL21 and required for lymphocyte exiting through HEVs.

- Nonetheless, it has been shown in a murine model that neutrophil homing to lymph nodes via the HEV takes place and requires integrins αMβ2 (MAC-1), αLβ2 (LFA-1), and L- and P-selectin.

- In lymph node-draining inflammatory tissue, additional chemokines and cytokines could orchestrate the attraction of neutrophils via HEVs.

- 2) Neutrophil migration to lymph nodes via afferent lymphatics has been observed in various murine models of infections, vaccinations, and cancer and seems to depend on MAC-1 and CXCR4 expression on neutrophils.

- 1) The first route requires exiting the circulation via high endothelial venules (HEVs). This mechanism is controversial, as human neutrophils seem to lack the expression of CCR7, a receptor for CCL21 and required for lymphocyte exiting through HEVs.

- Neutrophils have been reported to occupy the medullary region and interfollicular zone in the spleen. There they exhibit short and long-term interactions with B cells, thereby inhibiting production of antibodies, and thus humoral responses.

- Neutrophils have been observed to contribute to antibody production and class switching by activating B cells by producing BAFF, APRIL, and IL-21.

- Neutrophils might facilitate the development of this antigen-specific response as they may serve as antigen-presenting cells in influenza infection in mice. For instance, in mice, antigen presentation by influenza-infected neutrophils was found to be mediated by MHC-I and costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, which leads to induction and activation of anti-viral responses of CD8+ T cells.

- In the early course of infection, large numbers of neutrophils are recruited to the affected tissue where modulation of T cell responses most likely occurs with early recruited T cells. These early lymphocytes mainly belong to the family of γδ T cells.

- These γδ T cells are thought to play a role in early pathogen clearance through production of cytokines and their crosstalk with innate immune cells. Neutrophils recruit γδ T cells and may also play an important role in the limitation or suppression of γδ T cell responses.

- Phagocytosis of some bacteria enables neutrophils to activate γδ T cells and induce their proliferation. This is dependent on (1) the microbial metabolite (E)-4-hydroxy-3- methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMB-PP), which neutrophils release after phagocytosis of bacteria and (2) the presence of monocytes for cellular contact-induced activation.

- Human studies have revealed the ability of neutrophils to suppress γδ T cell activation, possibly providing a negative feedback mechanism.

Heterogenic Nature of Neutrophils

- Neutrophils were thought to be composed of a homogenous population, however an increasing body of literature supports the presence of multiple neutrophil phenotypes in cancer and inflammation.

- Heterogeneity can be induced by specific differentiation programs in the bone marrow or orchestrated by extracellular signals derived from inflammatory tissue (e.g. cytokines, bioactive lipids, or chemokines).

- The contribution of distinct neutrophil populations to immune suppression is still being studied.

- One of the key remaining issues is whether human neutrophils show functional plasticity. This plasticity can occur at different levels: (1) the existence of functional subsets, which are intrinsically different or (2) the transdifferentiation into suppressive neutrophils or even, but this remains controversial, into an antigen-presenting cell type or hybrid cell.

- The microenvironmental cues mediating the switch from classical neutrophils to suppressive neutrophils are still being studied although TGF-β seems to play an important role in microbial and tumor models.

- It has been recently described that neutrophils can have a prolonged lifespan. They also have the ability to de novo synthesize cytokines, and to recirculate through different tissues and organs, which extends their repertoire of immunomodulatory functions by interacting and modulating the immune response exerted by both the innate and adaptive systems.

- These recently identified properties of neutrophils align with the increasing evidence for the existence of neutrophil subpopulations with distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics.

- Understanding neutrophil heterogeneity may be instrumental to develop novel therapies that specifically target pathogenic neutrophil subsets without compromising immunity.

Neutrophils in Leishmaniasis

- See Section 12 – Immunity to Leishmania

- Experimental mouse models have been used to investigate the immune response to infection with different species of Leishmania parasites and to study host-parasite interactions.

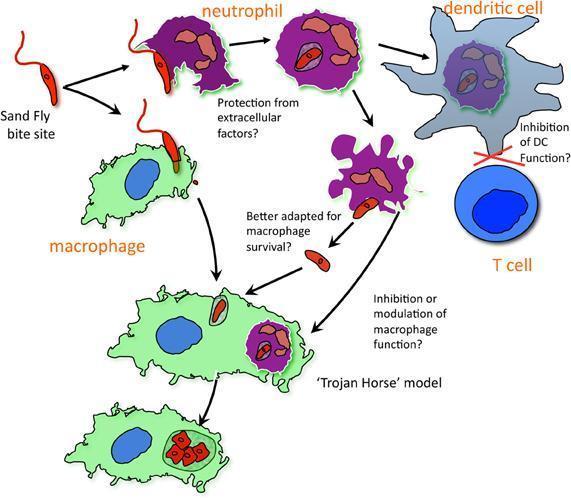

- Such models have demonstrated that neutrophils are rapidly recruited to the local site of inoculation of Leishmania parasites.

- Neutrophils quickly phagocytose promastigotes, and their response to the parasite, including secretion of antimicrobial peptides, reactive oxygen species, cytokines and chemokines as well as NET formation is likely to shape the subsequent immune response and the outcome of infection.

- Neutrophils have been shown to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in response to Leishmania, which trap and may kill the parasites.

- However, it has been proposed that neutrophils may act as a ‘safe haven’ for Leishmania, providing protection for the parasites until their long-term host cells – macrophages – are recruited.

- Apoptotic infected neutrophils may then be phagocytosed by macrophages to allow silent entry by a ‘Trojan horse’ mechanism. In macrophages, promastigotes can change into amastigotes and proliferate.

Quiz

Download Relevant Resources for this section:

Survival Mechanisms Used by some Leishmania spp to escape Neutrophil Killing

1 file(s) 208.57 KB

References

- Bellanti, JA (Ed). Immunology IV: Clinical Applications in Health and Disease. I Care Press, Bethesda, MD, 2012

- Leliefeld, P. Koenderman, L. and Pillay, J. (2015) How neutrophils shape adaptive immune responses. Front. Immunol. 6:471.

- Kolaczkowska, E. and Kubes, P. (2013). Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunol. 13, 159-175

- Silvestre-Roig, C., and

- Ribeiro-Gomes, F. and Sacks, D. (2012). The influence of early neutrophil-Leishmania interactions on the host immune response to infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 04 May 2012

- Laskay, T., van Zandbergen, G., and Solbach, W. (2003). Neutrophil granulocytes -Trojan horses for Leishmania major and other intracellular microbes? Trends Microbiol. 11, 210–214.

- Peters, N.C., Egen, J.G., Secundino, N., Debrabant, A., Kimblin, N., Kamhawi, S., Lawyer, P., Fay, M.P., Germain, R.N., and Sacks, D. (2008). In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science 321, 970–974.

- Schuster, S., Hurrell, B. and Tacchini-Cottier, F. (2013). Crosstalk between neutrophils and dendritic cells: a context-dependent process. J Leukoc Biol. 94(4):671-5

References

- Bellanti, JA (Ed). Immunology IV: Clinical Applications in Health and Disease. I Care Press, Bethesda, MD, 2012

- Leliefeld, P. Koenderman, L. and Pillay, J. (2015) How neutrophils shape adaptive immune responses. Front. Immunol. 6:471.

- Kolaczkowska, E. and Kubes, P. (2013). Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunol. 13, 159-175

- Silvestre-Roig, C., and

- Ribeiro-Gomes, F. and Sacks, D. (2012). The influence of early neutrophil-Leishmania interactions on the host immune response to infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 04 May 2012

- Laskay, T., van Zandbergen, G., and Solbach, W. (2003). Neutrophil granulocytes -Trojan horses for Leishmania major and other intracellular microbes? Trends Microbiol. 11, 210–214.

- Peters, N.C., Egen, J.G., Secundino, N., Debrabant, A., Kimblin, N., Kamhawi, S., Lawyer, P., Fay, M.P., Germain, R.N., and Sacks, D. (2008). In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science 321, 970–974.

- Schuster, S., Hurrell, B. and Tacchini-Cottier, F. (2013). Crosstalk between neutrophils and dendritic cells: a context-dependent process. J Leukoc Biol. 94(4):671-5