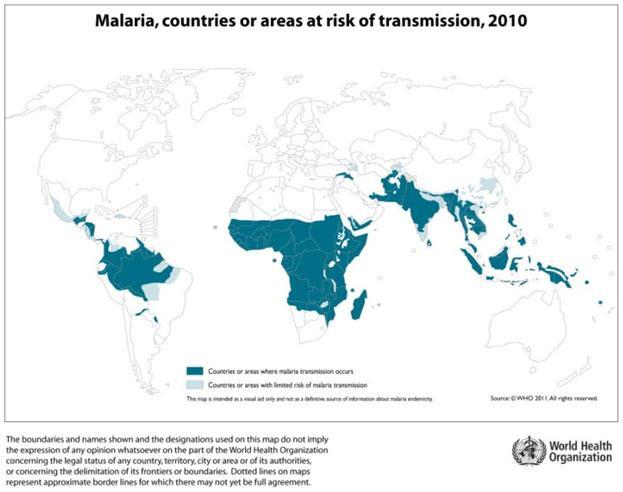

Malaria is a vector borne disease, caused by an intracellular parasite, the protozoan Plasmodium spp. It affects most tropical areas of the world (Figure 1), where mosquitos of the Anopheles genus are present. Young children and pregnant women are especially vulnerable to malaria infection, and most of the mortality occurs among children under 5 years of age.

Malaria Life-Cycle

- Malaria can be caused by one of 5 Plasmodium species: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and the zoonotic monkey parasite, P. knowlesi.

- The classical symptom of malaria is a cyclical fever pattern occurring every two days in P. falciparum, P. vivax, and P. ovale infections (tertian fever).

- Severe malaria is almost exclusively caused by P. falciparum infection and is associated with severe anaemia or coma and death if untreated.

- P. knowlesi can also cause very severe disease. Splenomegaly, severe headache, cerebral ischemia, hepatomegaly, and hemoglobinuria with renal failure, i.e., black water fever, may also be seen in severe malaria.

- Recurrent malaria is seen in both P. vivax and P. ovale infections and the disease can relapse months or years after initial infection, with recurrent waves of parasitemia emanating from the persistence of latent parasites (hypnozoites) in the liver.

- P. falciparum does not form hypnozoites but, if not treated, individual blood stage infections may persist at oscillating density for up to 3 years.

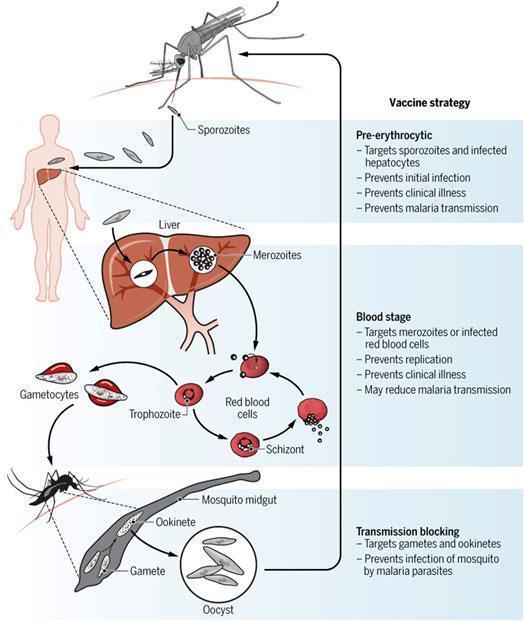

The malaria life cycle is complex and occurs in 2 host species: humans or monkeys and mosquitoes Figure 2.

Malaria transmission and the infective sporozoite stage

- Humans are only infected by the plasmodium sp., sporozoite stage, which is responsible for the natural transmission of the disease.

- Infective sporozoites develop in the salivary glands of female Anopheles mosquitos and during a blood meal a few hundred (~10 –100) are injected into the host skin.

- In the skin the sporozoites actively migrate in a substrate-dependent manner known as gliding motility in order to quickly and efficiently find a blood vessel where they will be carried out with the blood flow into the liver.

- One thing is common: both in vivo and in vitro sporozoites move at a high average speed of 1-2 um/sec, making them one of the fastest eukaryotic cells known.

- The fact that the skin makes the first mammalian barrier for the sporozoite together with the unique features of their mechanical proteins makes them good targets for the development of new anti-malarial drugs.

- Immunity against a protein of the membrane of the sporozoite, the circumsporozoite protein, is also responsible for the most advanced trial vaccine to date, the RTS,S.

Basics of innate and adaptive antimalarial immunity

- While multiple Plasmodium species can cause malaria, Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for most cases and deaths, particularly in Africa (Figure 1) and has been the major focus of vaccine development.

- With repeated exposure, partial (non-sterile) protective immunity can develop and may reduce the frequency and severity of subsequent clinical episodes, but natural complete immunity to infection (sterilizing immunity) rarely, if ever occurs and it is only induced under experimental infection.

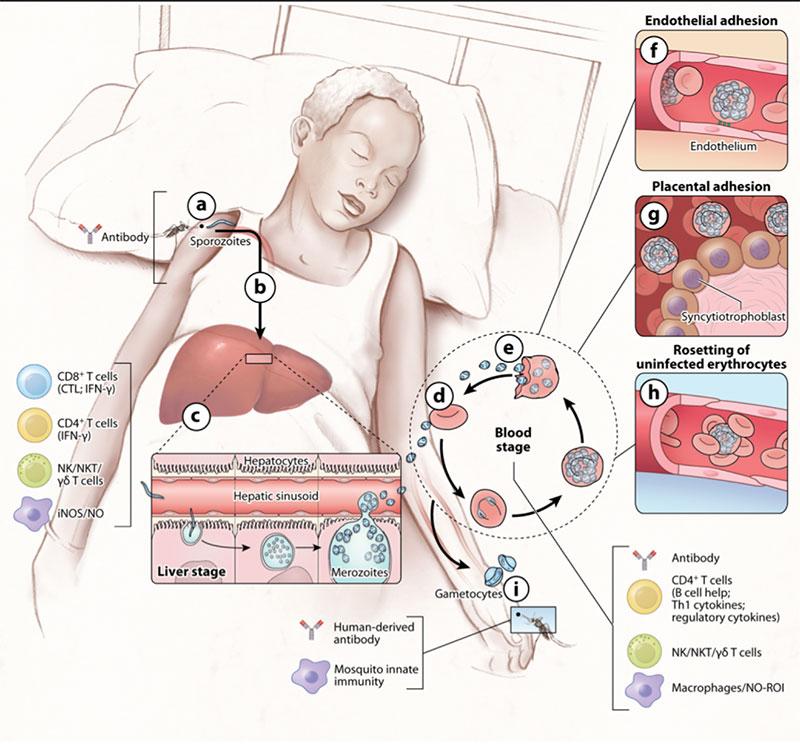

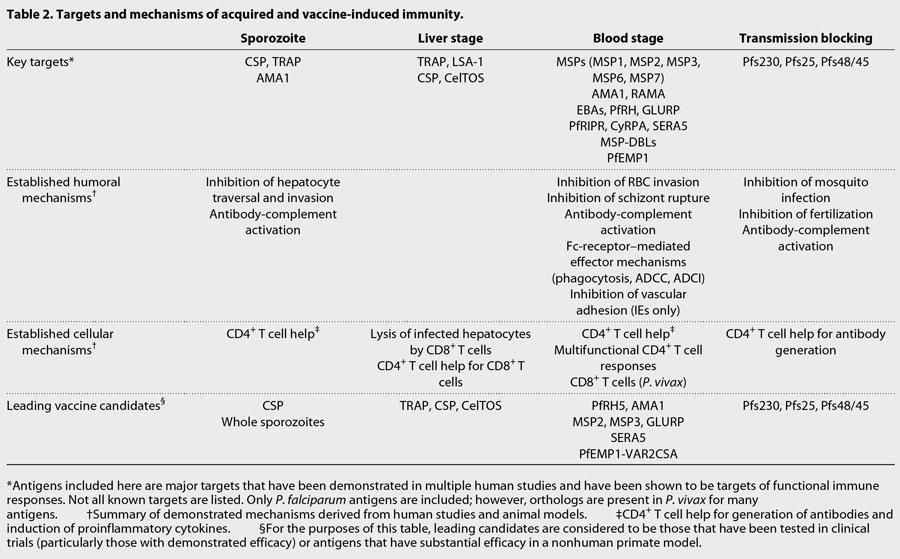

- Both humoral (antibody-mediated) and cell-mediated immunity mechanisms are important contributors for the development of acquired immunity against malaria (Figure 3).

- Below are some of the presumed mechanisms of adaptive immunity to malaria that are also described in more detail in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 2.

Pre-erythrocytic stages (skin/sporozoite and liver stages):

- Antibodies trap sporozoites in the skin by decreasing sporozoite motility (neutralizing antibodies), and block invasion of sporozoites into hepatocytes.

- Immunization with attenuated sporozoites (whole sporozoites) induces sterilizing immunity that appears to rely on adaptive CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, inhibiting parasite development in hepatocytes (cytotoxic T cell response). Here early and late attenuated sporozoites can be distinguished depending on whether they stop their development early or late in the liver.

- The immune responses against late attenuated liver stages are less well understood.

Erythrocytic stages:

- Antibodies block invasion of merozoites into erythrocytes and prevent sequestration of infected erythrocytes by preventing binding to adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelium.

- Antibodies opsonise merozoites and infected erythrocytes for enhanced phagocytosis IFN-y and CD4+ T cells activate macrophages to phagocytose intra-erythrocytic parasites and free merozoites.

- Antibodies neutralize parasite glycosylphosphatidylinositol and inhibit induction of the inflammatory cytokine cascade.

Transmission stages:

- Antibodies mediate complement-mediated cytolysis of extracellular gametes and prevent fertilization of gametes and the development of zygotes in the mosquitos.

Malaria Vaccine development

- Three types of vaccine strategies are being attempted (Figure 1): pre-erythrocytic vaccines, blood stage vaccines and transmission blocking vaccines.

- The key boosting antigens being used to develop the most advanced subunit vaccines are described in table 2, including the leading vaccine antigen candidate, the circumsporozoite protein or CSP (RTS,S vaccine).

- However, the need for a highly effective and long-lasting malaria vaccine remains strong. For that a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of immunity is necessary.

- Also, achieving higher efficacy may require the inclusion of multiple antigens which can be achieved for example by the use of whole attenuated parasites, such as genetically-attenuated parasites, a strategy also under development.

Malaria Immune Escape

- The high speed motility of the sporozoite and ability to traverse a diverse range of cells, including immune cells, which contributes to the inactivation of immune defences.

- From the blood, the parasites enter the liver. For the sporozoites to invade the hepatocytes, they must cross an endothelial barrier and phagocytic cells known as Kupffer Cells. Mouse models have shown that sporozoites modulate cytokine production of Kupffer cells, down-regulated Th1 responses and upregulating protective IL-10 production.

- During blood stage infection, parasites evade complement by the inhibition of the formation a membrane attack complex.

- Plasmodium survive inside red blood cells which also helps them evade immune responses as red blood cells do not express MHC class I molecules which means the parasite escapes CD8+ T cell responses.

- Sequestration is a characteristic of Plasmodium falciparum. It is a process where infected red blood cells adhere to the endothelium of capillaries and venules and thus, the parasites escape filtering by the spleen (Figure 3). This phenomenon is mediated parasite exported proteins, collectively called variant surface antigens or in short VSA. These proteins whilst highly immunogenic are also highly antigenically diverse evolving under high selective pressure from the immune system.

- Malaria parasites also lead to the formation of rosettes – a phenomenon where infected red blood cells cluster together with uninfected red blood cells which helps the parasite to hide from immune recognition (Figure 3).

Genomic insights into malaria population genetics

- Completion of the first genome sequence of falciparum in 2002 (P. falciparum 3D7 genome) was essential for continued progress towards malaria control and elimination. It was described as 22.9 Mb and essentially complete, with 14 chromosomes, a G+C content of approximately 19% and 5268 genes. Large-scale resequencing of global P. falciparum isolates is now being conducted. Sequences of other Plasmodium species are also already available, such as for Plasmodium vivax.

- The still lack of an efficient vaccine may result, among other reasons, from the fact that usually highly immunogenic proteins are also under high selective pressure and consequently are highly polymorphic. So proper surveillance of the parasite population is important to track these variations and to determine the extent of genetic diversity among populations.

- In addition, emerging drug resistant strains are associated with specific genetic polymorphisms. In South-East Asia, multiple SNPs in the kelch13 gene on chromosome 13 of falciparum were recently associated with artemisinin resistance. At least 20 different resistant alleles were identified. Identifying these genetic differences is essential to track their spread/and or emergence in other areas of the world.

- Factors like transmission intensity, drug usage policy and vector species can all account for the emergence of drug resistance.

- Worldwide three transmission endemic settings can be distinguished: 1) Low transmission settings, such as in South America 2) Low, moderate and high transmission settings in Asia-Pacific and 3) High transmission settings in Africa.

- Genomic studies highlight that in high transmission settings multiple clone infections are more common than in low transmission settings. This leads to variations in gene flow within and between populations and consequently to higher or decreased genetic diversity.

At the end, genomics studies of Plasmodium populations shed new light on the prevalence and importance of mixed infections with different parasite species or intraspecific variants with or without epidemiological importance such as drug resistance and virulence and also to track their transmission dynamics.

Quiz

Download the Presentations for this section:

Download these Resources:

Related Talk

Jeff Dorfman, University of Cape Town – The Immune Mechanisms of Fighting a Malaria Infection

References

-

- Douglas RG et al. Active migration and passive transport of malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol.2015 Aug;31(8):357-62. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.04.010.

- De Niz M et al. Intravital imaging of host parasite interactions in skin and adipose tissues. Cell Microbiol.2019 May;21(5):e13023. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13023.

- Spreng B et al. Microtubule number and length determine cellular shape and function in Plasmodium. EMBO J.2019 Aug 1;38(15):e100984. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100984.

- Conrad MD et al. Antimalarial drug resistance in Africa: the calm before the storm? Lancet Infect Dis.2019 Oct;19(10):e338-e351. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30261-0.

- Amambua-Ngwa A et al. Major subpopulations of Plasmodium falciparumin sub-Saharan Africa. 2019 Aug 23;365(6455):813-816. doi: 10.1126/science.aav5427.

- Auburn S et al. Dissecting malaria biology and epidemiology using population genetics and genomics. Int J Parasitol. 2017 Feb;47(2-3):77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.08.006.

- James G. Beeson et al. Challenges and strategies for developing efficacious and long-lasting malaria vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474). pii: eaau1458. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1458.

- Langhorne J et al. Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers.Nat Immunol.2008 Jul;9(7):725-32. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.205.

- Crompton PD et al. Malaria immunity in man and mosquito: insighs into unsolved mysteries of a deadly infectious disease.Annu Rev Immunol.2014;32:157-87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120220.

- Bediako Y et al. Repeated clinical malaria episodes are associated with modification of the immune system in children. BMC Med.2019 Mar 13;17(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1292-y.

-

- Douglas RG et al. Active migration and passive transport of malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol.2015 Aug;31(8):357-62. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.04.010.

- De Niz M et al. Intravital imaging of host parasite interactions in skin and adipose tissues. Cell Microbiol.2019 May;21(5):e13023. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13023.

- Spreng B et al. Microtubule number and length determine cellular shape and function in Plasmodium. EMBO J.2019 Aug 1;38(15):e100984. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100984.

- Conrad MD et al. Antimalarial drug resistance in Africa: the calm before the storm? Lancet Infect Dis.2019 Oct;19(10):e338-e351. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30261-0.

- Amambua-Ngwa A et al. Major subpopulations of Plasmodium falciparumin sub-Saharan Africa. 2019 Aug 23;365(6455):813-816. doi: 10.1126/science.aav5427.

- Auburn S et al. Dissecting malaria biology and epidemiology using population genetics and genomics. Int J Parasitol. 2017 Feb;47(2-3):77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.08.006.

- James G. Beeson et al. Challenges and strategies for developing efficacious and long-lasting malaria vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474). pii: eaau1458. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1458.

- Langhorne J et al. Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers.Nat Immunol.2008 Jul;9(7):725-32. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.205.

- Crompton PD et al. Malaria immunity in man and mosquito: insighs into unsolved mysteries of a deadly infectious disease.Annu Rev Immunol.2014;32:157-87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120220.

- Bediako Y et al. Repeated clinical malaria episodes are associated with modification of the immune system in children. BMC Med.2019 Mar 13;17(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1292-y.