Introduction to viral Infections

Viruses are infectious agents that only replicate inside of living cells.

The viral replication cycle follows a typical pattern:

- Attachment and entry: The virus attaches to the host cell membrane via specific receptors and enters the host cell, delivering its genetic material into the cell.

- Replication and Assembly: The virus uses the host cell’s machinery to replicate its viral genome and to produce new infectious particles.

- Release: Newly produced viruses are released from the host cell by lysis or budding.

The tropism or specificity for certain host cells of a virus is determined by the expression of specific receptors on the host cell membrane (e.g. HSV-1 and Polioviruses infect neurons, HIV infects CD4+ T cells [and macrophages]).

There are two types of viral infection: Acute (cytolytic) and persistent (chronic or latent).

In acute cytolytic viral infections, the virus infects a target cell by binding to specific surface receptors, and after a short phase of viral replication, destroys its host cell (e.g. poliovirus, smallpox, rubeola, mumps, influenza). Lysis of the host cell results in release of infectious virus particles, which are able to infect other target cells nearby but can also travel to distal sites.

Viruses causing persistent infections can be subdivided into latent (e.g. HSV, VZV) and chronic (e.g. HIV, HPV) viruses. These viruses are not cleared from the host following primary infection, but remain inside the host cell without causing rapid cell destruction and disease. In contrast to latent infections, where no infectious viral particles can be detected, chronic infection is characterised by continuous presence of viral particles after primary infection. Often in persistent infections viral nucleic acids are integrated into the host’s genetic apparatus (direct or episomal).

Immune response to viral infections

Innate immunity

- To infect an individual and to access susceptible target cells, a virus first has to break through the natural anatomical barriers of the skin or mucous membranes.

- Pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immune system as Toll-like receptors (TLRs); NOD-like receptors (NLRs); RIG-like helicases (RLH); DNA sensors can sense the presence of viral nucleic acids and proteins and trigger signalling pathways in the cell that lead to expression of antiviral chemokines and cytokines and put the cell into an antiviral state (degradation of all viral and host mRNA and proteins, apoptosis, protection of neighbouring cells, MHC-I upregulation).

List of TLRs involved in recognition of viral nucleic acids

[table id=180 /]

Table 1. List of TLRs involved in recognition of viral nucleic acids. [Bellanti, JA (Ed). Immunology IV: Clinical Applications in Health and Disease. I Care Press, Bethesda, MD, 2012]

- The first cytokines produced are primarily Interferon (IFN)-α and IFN-β as well as tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

- Macrophages and dendritic cells provide a link to the adaptive immunity by taking up virions and degrading them for presentation to T cells.

- Many viruses downregulate MHC-I expression on their host cells, evading recognition by T cells, however, natural killer (NK) cells are programmed to recognise and kill cells lacking MHC-I molecules.

IFNs as 1st responders to viral infections

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are a unique dendritic cell subset that specializes in the production of type I interferons (IFNs)

- pDCs produce type I IFNs following their recognition of viruses or self-nucleic acids through Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. pDCs can also express TLR2 and TLR12.

- TLR7 and TLR9 signal through a combination of MyD88-NF-kB and MyD88-IRF7 pathways.

- In addition to TLRs, pDCs express several cytosolic sensors of nucleic acids, some of which have been established to induce pDC activation and IFN-I production.

- pDCs are a prominent link between innate and adaptive immune responses. Their ability to rapidly produce type I IFNs (IFN-Is) during viral infections promotes an antiviral state by inducing expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISG) and apoptosis of infected cells.

- Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), the most potent IFN-I-producing cells, rapidly respond to murine and human persistent viruses by releasing copious amounts of these cytokines

Type I interferon (IFN-I) family

- The Type I interferon (IFN-I) family are antiviral and antineoplastic cytokines critical for the control of most types of viral infections.

- This family includes 13 subtypes of IFN-α in humans (14 in mice) one IFN-β.

- While all cell types can produce IFN-I, plasmacytoid (p) dendritic cells (DCs) produce IFN-I and other interferons at exceptional levels, including all 13 subtypes of IFN-α, IFN-β, and 3 subtypes of IFN-λ, and IFN-τ.

- Type I interferons (IFNs-I) provide critical resistance to infections and tumors by limiting the spread of the infectious agent or malignant transformation and by activating multiple innate and adaptive immune cells.

- IFNβ and all IFNα subtypes bind and signal through a heterodimeric transmembrane Receptor (IFNAR) composed of the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits.

- IFNα/β induces the expression of several hundred ISGs (IFN-stimulated gene factors), a large number of which act to induce an antiviral state within the cell.

- IFNα/β have effects on both the innate and adaptive cellular immune response. The action of IFNα/β includes effects on myeloid cells, B cells, T cells and natural killer (NK) cells that act to enhance the immune response, more effectively resolve viral infection and improve the generation of memory responses for reacting to future viral challenge.

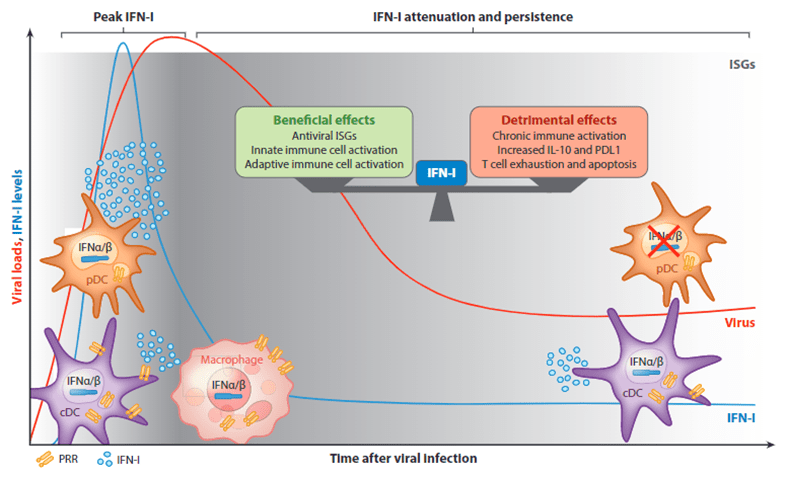

- IFN-I have critical importance to control viral infections but the consequences of IFN-I are not exclusively beneficial. Excessive and/or late IFN-I is associated with increased mortality in several animal models of viral infection. IFNα/β can also be harmful in virus infection, either by immunosuppressive effects that impede viral control, promote secondary infections or by triggering inflammation and tissue damage that aggravate disease and could cause IFN-I-induced immunopathology.

Controlling IFN-I

- Several mechanisms may contribute to the attenuation of IFN-I in the post-acute stages of chronic viral infections, including (a) direct suppression of innate pathways by viral products and (b) host immunomodulatory mechanisms.

- Cell responses to newly produced type I IFNs are modified by feedback mechanisms that are activated by type I IFNs and by heterologous signals that are generated by microbial factors and host cytokines.

- Viruses such as HSV, hepatitis C (HCV), dengue and HIV have dedicated some of their viral proteins to inhibit IFN-I signalling.

- Viral proteins act at different stages of IFN-I production pathways: Inhibit viral sensing by blocking TLR3, RIG-I and MAVS, (antagonizing sensing of dsRNA), as well as blocking of IRF3 activation or inducing IRF3 degradation and can also inhibit TLR9, and evade PRR sensing in macrophages

- Viruses and tumour cells also induce IFNAR degradation to evade type I IFN-mediated antiviral responses and antitumour effects, respectively. Internalization of IFNAR is induced by various heterologous pathways to limit cellular IFN responsiveness.

pDC exhaustion

- Despite the importance of pDC derived IFN-I for the control of many viruses, after their initial activation pDCs rapidly lose their capacity to produce these antiviral mediators, a state that we refer to as “pDC exhaustion”

- These exhausted pDCs fail to produce IFN-I in response to the ongoing infection, synthetic toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, and/or unrelated viruses, and this functional exhaustion can favor prolonged viral replication and is accompanied by compromised innate responses and control of secondary opportunistic Infections.

- pDC exhaustion may have evolved as a “default” behavior to avoid the potentially harmful effects of sustained IFN-I production.

- pDC-derived-IFN-I production is also compromised in many infections by a reduction in pDC numbers.

- The mechanisms by which pDC numbers may be altered include reduction in development from bone marrow (BM) progenitors, increased apoptosis, changes in pDC proliferative capacity, and conversion of pDCs into conventional (c)DC-like cells.

- Long-term maintenance of exhausted pDCs involves both compromised numbers and IFN-I production capacity of pDC

- Whereas both IFN-I and TLR7 signaling contributed to peripheral pDC proliferation, only IFN-I was responsible for reduced pDC progenitors.

- IFN-I production in pDCs can be modified by receptors expressed on their surface. Diverse families of receptors have established roles in modulating pDC cytokine production downstream of ligation.

pDC and COVID-19

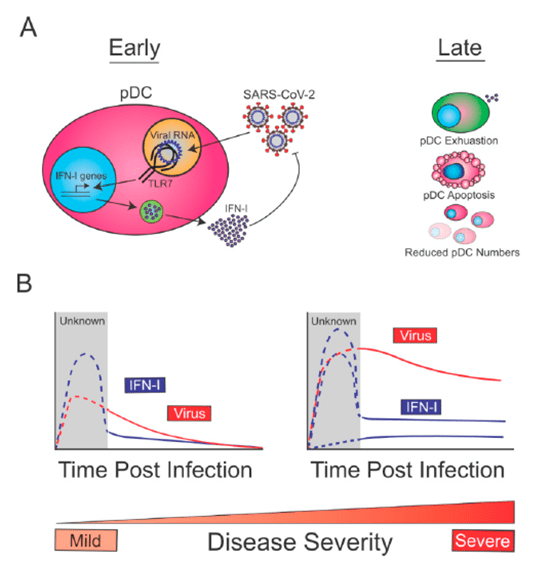

Proposed Model for the Biology and Role of pDCs in SARS-CoV-2 Infection:

- At early times post-infection, pDCs are sensing SARS-CoV-2 through TLR7, which drives the production of IFN-I, and contains SARS-CoV-2 replication (Figure 2A, left).

- At later time points post-infection, reduction in pDC numbers (exacerbated in severe cases due to increased apoptosis) and decreased pDC function (exhaustion), may lead to reduced pDCderived IFN-I (Figure 2A, right).

- Given that early pDC-derived IFN-I is expected to be beneficial for the host to control SARS-CoV-2, this immune function is likely intact in patients with mild disease (Figure 2B, left).

- On the other hand, COVID-19 severe cases may show diverse profiles of pDC-derived-IFN-I (Figure 2B, right).

Quiz

Download these Resources:

References

- Greene, T. T., & Zuniga, E. I. (2021). Type I Interferon Induction and Exhaustion during Viral Infection: Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells and Emerging COVID-19 Findings. Viruses, 13(9), 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091839

- Labarta-Bajo, L., Nilsen, S. P., Humphrey, G., Schwartz, T., Sanders, K., Swafford, A., Knight, R., Turner, J. R., & Zúñiga, E. I. (2020). Type I IFNs and CD8 T cells increase intestinal barrier permeability after chronic viral infection. The Journal of experimental medicine, 217(12), e20192276. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20192276

- Lukhele, S., Boukhaled, G. M., & Brooks, D. G. (2019). Type I interferon signaling, regulation and gene stimulation in chronic virus infection. Seminars in immunology, 43, 101277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2019.05.001

- Macal, M., Jo, Y., Dallari, S., Chang, A. Y., Dai, J., Swaminathan, S., Wehrens, E. J., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P., & Zúñiga, E. I. (2018). Self-Renewal and Toll-like Receptor Signaling Sustain Exhausted Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells during Chronic Viral Infection. Immunity, 48(4), 730–744.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.020

- McNab, F., Mayer-Barber, K., Sher, A., Wack, A., & O’Garra, A. (2015). Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nature reviews. Immunology, 15(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3787

- Zuniga, E. I., Macal, M., Lewis, G. M., & Harker, J. A. (2015). Innate and Adaptive Immune Regulation During Chronic Viral Infections. Annual review of virology, 2(1), 573–597. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055226

- Greene, T. T., & Zuniga, E. I. (2021). Type I Interferon Induction and Exhaustion during Viral Infection: Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells and Emerging COVID-19 Findings. Viruses, 13(9), 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091839

- Labarta-Bajo, L., Nilsen, S. P., Humphrey, G., Schwartz, T., Sanders, K., Swafford, A., Knight, R., Turner, J. R., & Zúñiga, E. I. (2020). Type I IFNs and CD8 T cells increase intestinal barrier permeability after chronic viral infection. The Journal of experimental medicine, 217(12), e20192276. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20192276

- Lukhele, S., Boukhaled, G. M., & Brooks, D. G. (2019). Type I interferon signaling, regulation and gene stimulation in chronic virus infection. Seminars in immunology, 43, 101277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2019.05.001

- Macal, M., Jo, Y., Dallari, S., Chang, A. Y., Dai, J., Swaminathan, S., Wehrens, E. J., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P., & Zúñiga, E. I. (2018). Self-Renewal and Toll-like Receptor Signaling Sustain Exhausted Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells during Chronic Viral Infection. Immunity, 48(4), 730–744.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.020

- McNab, F., Mayer-Barber, K., Sher, A., Wack, A., & O’Garra, A. (2015). Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nature reviews. Immunology, 15(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3787

- Zuniga, E. I., Macal, M., Lewis, G. M., & Harker, J. A. (2015). Innate and Adaptive Immune Regulation During Chronic Viral Infections. Annual review of virology, 2(1), 573–597. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055226