Metabolism of Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the immune system and constitute a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. DCs comprise a highly heterogeneous cell population able to receive and interpret signals either from invading pathogens or dying cells, and to respond to them through the acquisition of a mature phenotype. The uptaken and processed antigens are presented to T cells, both under inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions. Therefore, DCs are gatekeepers of immunity and peripheral tolerance.

Characteristics and phenotypes:

- DCs are derived from bone marrow precursor cells and are constantly replenished. As an exception, Langerhans cells have a self-renewal capacity in the epidermis. These DC precursor cells give rise to several DC subpopulations, which can be distinguished by their: localization, migration capacity and subset specific expression profiles (cytokines, chemokines, transcription factors, surface markers, pattern recognition receptors).

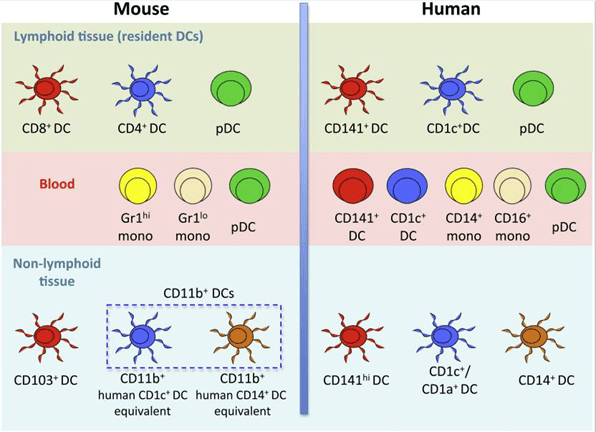

- In human and mouse, DCs can be broadly subdivided into classical DCs (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs)

- DCs are categorized into lymphoid-tissue-resident (e.g. blood, bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus) and non-lymphoid-tissue migratory DC subpopulations (e.g. intestine, skin, lung, mucosa) (Figure 1).

- There are two major subsets of human DCs (lymphoid-tissue-resident)

- Plasmacytoid (pDCs)

- Conventional/classical DCs, consisting of two subsets: CD1c+ DCs (mouse: CD4+ DCs) and CD141+ DCs (mouse: CD8+ DCs).

- Non-lymphoid-tissue-resident DCs are less well characterized and include several subsets that express surface markers that allow their distinction (Figure 1).

- Important and characteristic human DC surface molecules are:

- pDCs: CD123, CD303 (BDCA-2), CD304 (BDCA-4), HLA-DR, CD11cneg

- CD1c+ DCs: CD1c, Sirp-α, HLA-DR, CD11chigh

- CD141+ DCs: CD141, Clec9A, XCR1, HLA-DR, CD11cint

- Important and characteristic mouse DC surface molecules are:

- pDCs: PDCA-1, B220, Siglec-H, CCR9, MHC-IIint, CD11cint

- CD4+ DCs: CD4, CD11b, Sirp-α, MHC-IIhigh, CD11chigh

- CD8+ DCs: CD8, Clec9A, XCR1, MHC-IIhigh, CD11chigh

Dendritic cell function

In the steady-state (non-inflammatory conditions) DCs are immature. Upon pathogenic encounter, DCs start to mature. This process of maturation is accompanied by the upregulation of co-stimulatory and activator cell surface molecules, the secretion of cytokines and chemokines, and migration into lymphoid tissues. The processed antigens are presented in a complex with murine MHC (major histocompatibility complex) or human HLA (human leukocyte antigen) to T cells, leading to life-long immunity to the encountered pathogen. Also, innocuous self-antigens are constantly presented under non-inflammatory conditions in this manner, DCs are able to maintain peripheral tolerance by driving autoreactive T cells into anergy or apoptosis.

Antigen recognition and danger-sensing by:

- Pattern recognition receptors (PRR)

*C-type lectin receptors

*Toll-like receptors

*RIG-I receptors

*NOD receptors - Scavenger receptors

- Fc receptors

Antigen uptake by:

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis

- Phagocytosis

- Macropinocytosis

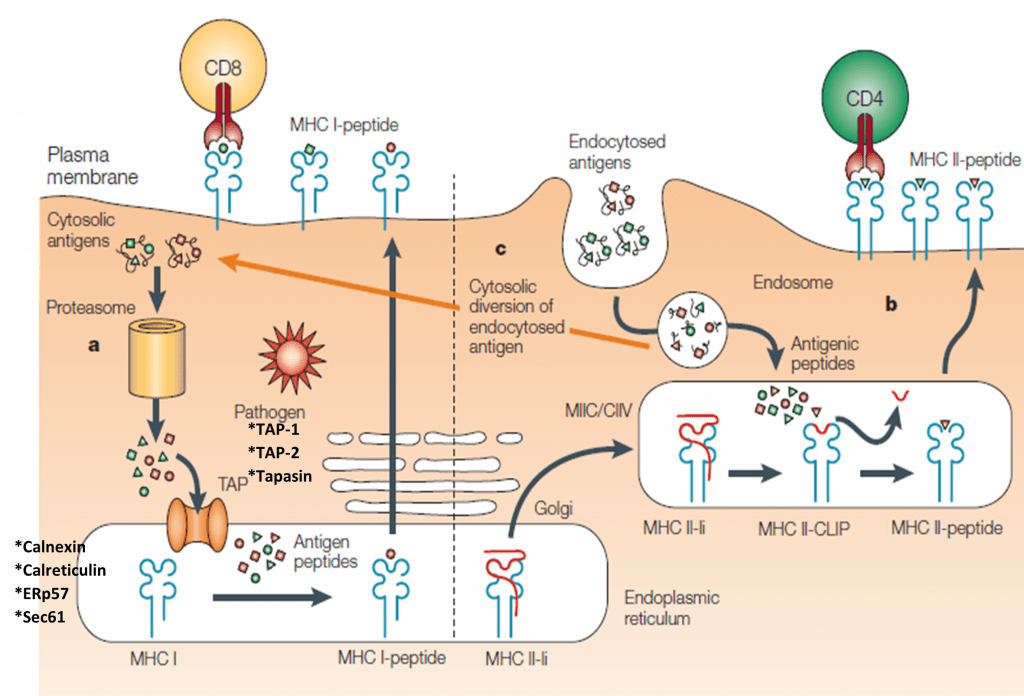

Antigen processing for HLA-ABC/MHC-I:

- Cytosolic (e.g. viral) antigens are cleaved in the proteasome and transferred via the TAP-transporter into the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER)

- Antigen loading as 8-10 amino acid long peptides onto HLA-ABC/MHC-I

- Transport via Golgi network to the cell surface

- Presentation of peptide-HLA-ABC/MHC-I complex to CD8+ T cells (Figure 2)

Antigen processing for HLA-DR/MHC-II:

- Extracellular antigens are degraded in the endosomal/lysosomal compartments

- Antigen loading for up to 30 amino acid long peptides onto HLA-DR/MHC-II

- Fusion of the HLA-DR/MHC-II peptide containing vesicles with the cell membrane

- Presentation of peptide-HLA-DR/MHC-II complex to CD4+ T cells (Figure 2)

- Exception: The presentation of e.g. intracellular peptides via HLA-DR/MHC-II is called autophagy.

- A unique specificity of DCs is cross-presentation, which describes a process when extracellular antigens are presented via HLA-ABC/MHC-I (Figure 2).

- In parallel to antigen processing and presentation, “danger”-sensing initiates both an enhanced expression profile of co-stimulatory (CD80, CD86) and activator molecules (CD40, CD83), as well as an increased cytokine production. The chemokine receptor CCR7 renders DCs responsive for CCL19 and CCL21, thus enabling DC migration to nearby lymph nodes. These DCs are now in a mature state.

- Once they arrive in secondary lymphoid organs (e.g. lymph nodes), DCs present peptides to antigen-specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cells.

- This leads to the establishment of an immunological synapse composed of the peptide MHC complex, co- stimulatory, and activator molecules on the APC side, as well as the TCR and its respective co-receptors on the T cell side.

Metabolic processes in DCs:

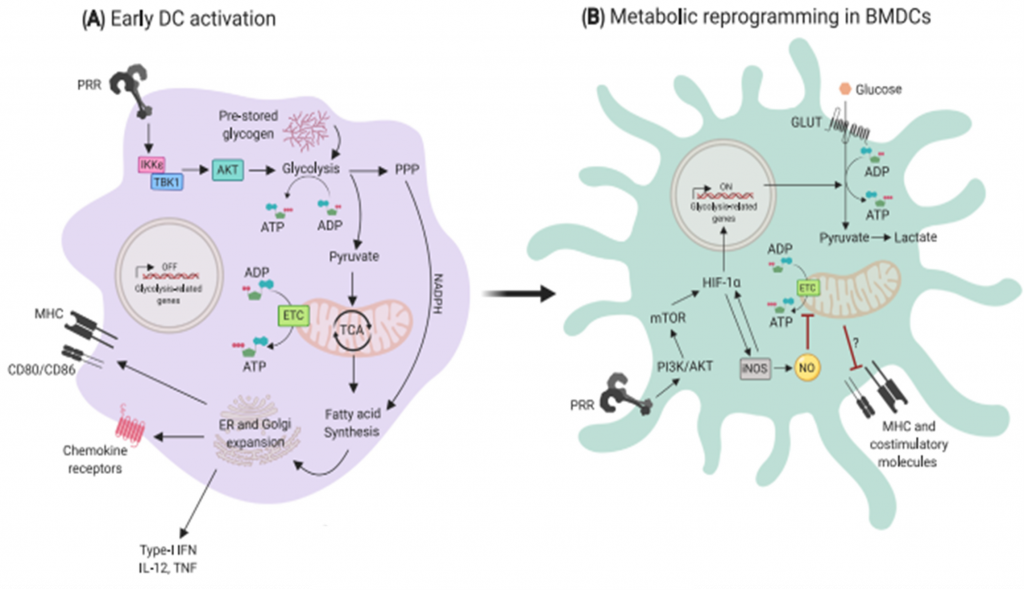

- Under resting conditions, DCs mainly rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for energy. This process occurs within mitochondria, whereby cells utilize NADH generated from the catabolism of nutrients (e.g. glucose, amino acids and fatty acids) to produce ATP through a series of reduction-oxidation reactions (Minarrieta et al, 2017).

- Upon PRR activation, they rapidly mature to a proinflammatory phenotype that is characterized by a robust increase in the production of diverse factors involved in antigen presentation, such as MHC molecules, cytokines and the costimulatory ligands CD80 and CD86 (Figure 3).

- Engagement of TLR on GM-CSF derived DCs leads to upregulation of aerobic glycolysis. This process, which is termed the “Warburg effect”, involves the conversion of glucose into lactate and is dependent on the PI3K/Akt pathway.

- In cancer cells, the Warburg effect accompanies rapid proliferation, whereas DCs are generally non-proliferative and do not divide further upon TLR ligation.

- Early glycolytic reprogramming in DCs increases the concentration of crucial metabolic intermediates that are essential for anabolic processes to sustain the production of DC activation-related molecules. These leads to increased concentrations of pyruvate that can be shuttled into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for the production of citrate (Figure 3).

- The export of citrate from mitochondria into the cytoplasm is particularly important for fueling fatty acid synthesis, which is linked to the requirement of activated DCs to increase the size of key organelles involved in protein synthesis and secretion: the ER and Golgi apparatus (O’Neill and Pearce, 2016).

- Fatty acid metabolism plays a critical role in the regulation of DC function:

- *Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): a study using immature and LPS-matured human monocyte-derived DCs revealed that both butyrate and propionate strongly reduced the expression of several proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines at the transcriptional level. Similar observations were made with murine bone marrow-derived DCs, where acetate, butyrate and propionate inhibited the LPS-induced expression of costimulatory molecules CD80, CD86 and CD40 and production of proinflammatory cytokines. DCs exposed to SCFAs also displayed a strong Treg-inducing capacity (Minarrieta et al.,2017)

- *Medium, long-chain and polyunsaturated fatty acids: can exert their function through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, a group of nuclear receptors that act in an anti-inflammatory manner, both by directly regulating gene expression as well as through interference with the prototypic inflammatory mediator NFkB.

- Vitamin A: all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) participates in maintaining the homeostasis of cDC subsets. The fate commitment of pre-cDCs into different DC subpopulations is dependent on the concentration of this metabolite.

- In particular, the development of splenic CD11b+CD8a- and small intestine LP CD11b+CD103+ DCs is severely impaired in absence of Vitamin A.

- Vitamin D: some studies showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment induces a tolerogenic phenotype in DCs

Quiz

Download these Resources:

References

- Giovanelli, P., Sandoval, T. A., & Cubillos-Ruiz, J. R. (2019). Dendritic Cell Metabolism and Function in Tumors. Trends in Immunology, 40(8), 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2019.06.004

- Haniffa, M., Shin, A., Bigley, V., McGovern, N., Teo, P., See, P., Wasan, P. S., Wang, X.-N., Malinarich, F., Malleret, B., Larbi, A., Tan, P., Zhao, H., Poidinger, M., Pagan, S., Cookson, S., Dickinson, R., Dimmick, I., Jarrett, R. F., … Ginhoux, F. (2012). Human Tissues Contain CD141hi Cross-Presenting Dendritic Cells with Functional Homology to Mouse CD103+ Nonlymphoid Dendritic Cells. Immunity, 37(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.012

- Heath, W. R., & Carbone, F. R. (2001). Cross-presentation in viral immunity and self-tolerance. Nature Reviews Immunology, 1(2), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/35100512

- O’Neill, L. A. J., & Pearce, E. J. (2016). Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 213(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20151570

- Stüve, P., Minarrieta, L., Erdmann, H., Arnold-Schrauf, C., Swallow, M., Guderian, M., Krull, F., Hölscher, A., Ghorbani, P., Behrends, J., Abraham, W.-R., Hölscher, C., Sparwasser, T. D., & Berod, L. (2018). De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis During Mycobacterial Infection Is a Prerequisite for the Function of Highly Proliferative T Cells, But Not for Dendritic Cells or Macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00495

- Giovanelli, P., Sandoval, T. A., & Cubillos-Ruiz, J. R. (2019). Dendritic Cell Metabolism and Function in Tumors. Trends in Immunology, 40(8), 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2019.06.004

- Haniffa, M., Shin, A., Bigley, V., McGovern, N., Teo, P., See, P., Wasan, P. S., Wang, X.-N., Malinarich, F., Malleret, B., Larbi, A., Tan, P., Zhao, H., Poidinger, M., Pagan, S., Cookson, S., Dickinson, R., Dimmick, I., Jarrett, R. F., … Ginhoux, F. (2012). Human Tissues Contain CD141hi Cross-Presenting Dendritic Cells with Functional Homology to Mouse CD103+ Nonlymphoid Dendritic Cells. Immunity, 37(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.012

- Heath, W. R., & Carbone, F. R. (2001). Cross-presentation in viral immunity and self-tolerance. Nature Reviews Immunology, 1(2), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/35100512

- O’Neill, L. A. J., & Pearce, E. J. (2016). Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 213(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20151570

- Stüve, P., Minarrieta, L., Erdmann, H., Arnold-Schrauf, C., Swallow, M., Guderian, M., Krull, F., Hölscher, A., Ghorbani, P., Behrends, J., Abraham, W.-R., Hölscher, C., Sparwasser, T. D., & Berod, L. (2018). De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis During Mycobacterial Infection Is a Prerequisite for the Function of Highly Proliferative T Cells, But Not for Dendritic Cells or Macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00495