Malaria is a mosquito-borne parasitic infection, caused by an intracellular parasite, the protozoan Plasmodium spp. It affects most tropical areas around the world where mosquitos of the Anopheles genus are located. Around 200 to 400 million people are infected each year, resulting in approximately 400,000 deaths annually. It typically causes morbidity and mortality in infants and young children in sub-Saharan Africa and most of the mortality occurs among children below the age of 5.

Plasmodium species

- Malaria can be caused by one of 5 Plasmodium species: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and the zoonotic monkey parasite, P. knowlesi.

- P. falciparum is the deadliest malaria parasite and the most prevalent on the African continent. P. vivax is the dominant malaria parasite in most countries outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Globally, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax account for the majority of cases of malaria.

- Severe malaria is almost exclusively caused by P. falciparum infection and is associated with severe anaemia or coma and death if untreated.

- P. knowlesi can also cause very severe disease. Splenomegaly, severe headache, cerebral ischemia, hepatomegaly, and hemoglobinuria with renal failure, i.e., black water fever, may also be seen in severe malaria.

- Recurrent malaria is seen in both P. vivax and P. ovale infections and the disease can relapse months or years after initial infection, with recurrent waves of parasitemia

Malaria life cycle

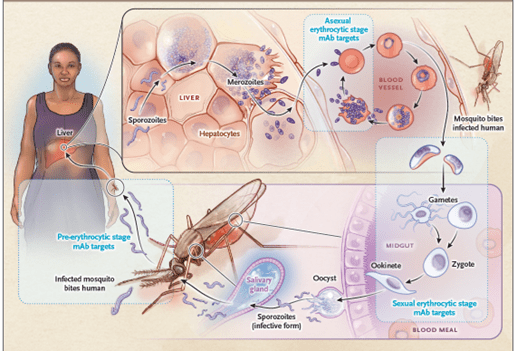

- The malaria life cycle is complex, and the parasite has two hosts – the human and the female Anopheles mosquito, which is also the vector. The stages of the life cycle include the pre-erythrocytic, asexual erythrocytic and sexual erythrocytic stages (Figure 1).

- Pre-erythrocytic stage (skin/sporozoite and liver stages)

- Infected mosquito bites human host and injects the plasmodium parasite from the saliva into the host tissues in the form of a sporozoite and infection is initiated.

- The sporozoites then infect the liver cells (hepatocytes) where they develop into merozoites.

- Asexual erythrocytic stage (red blood cell stage)

- The merozoites infect red blood cells (erythrocytes) and develop into trophozoites and schizonts containing up to 20 daughter merozoites.

- These merozoites then multiply and rapture the red blood cells and reinfect new erythrocytes.

- The synchronous release of merozoites from erythrocytes causes the cyclic fevers associated with malaria.

- Sexual erythrocytic stage

- A subset of developing merozoites differentiate into male and female gametocytes, which, when taken up by a feeding mosquito, give rise to extracellular gametes.

- In the mosquito mid-gut, the gametes fuse to form a motile zygote (ookinete), which penetrates the mosquito gut wall and forms an oocyst, within which meiosis takes place and haploid sporozoites develop.

Basics of innate and adaptive antimalarial immunity

- While multiple plasmodium species can cause malaria, Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for most cases and deaths, particularly in Africa, and has been the major focus of vaccine development.

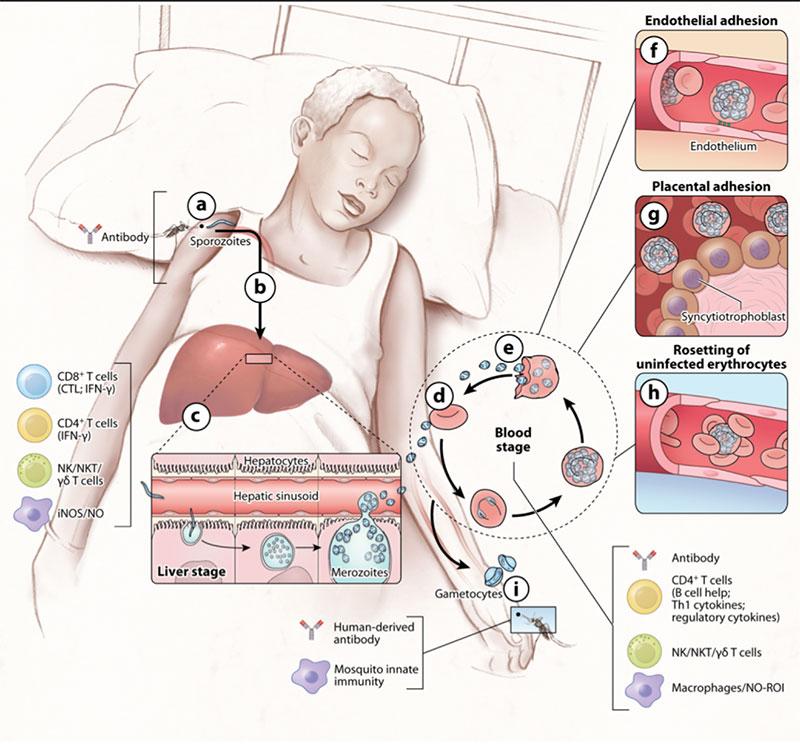

- Both humoral (antibody-mediated) and cell-mediated immunity mechanisms are important contributors for the development of acquired immunity against malaria (Figure 2).

Malaria Vaccine development

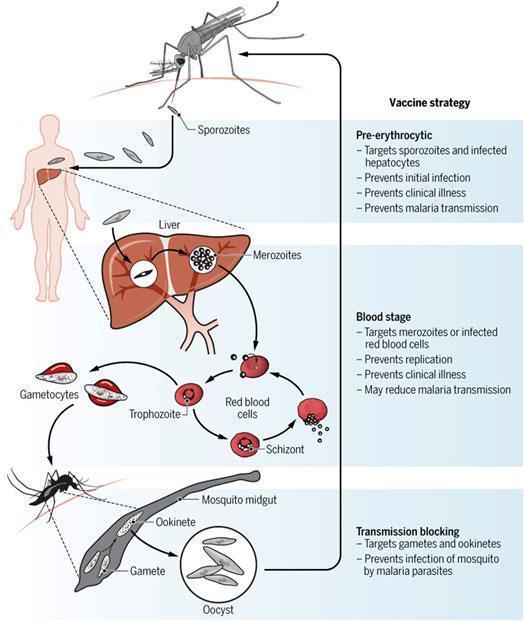

Three types of vaccine strategies have been attempted (Figure 3): pre-erythrocytic vaccines, blood stage vaccines and transmission blocking vaccines.

Ideally what is desired the most from attempts on vaccine development against malaria is a vaccine that can target the first stages of parasitic development i.e. sporozoites that develop during the pre-erythrocytic stage, such that transmission can be prevented altogether.

Immune responses to malaria vaccine candidates

- Malaria vaccine development strategies now seem to be focused on two main types of vaccines – subunit vaccines consisting of well-defined parasite antigens and vaccines based on the use of whole attenuated sporozoites.

- RTS,S/AS01 (also known as Mosquirix) is a recombinant protein-based malaria vaccine endorsed by WHO for use in children. It was engineered using genes from the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) on the sporozoite surface of the falciparum, a viral envelope protein of hepatitis B virus (HBsAg), and a chemical adjuvant (AS01). Infection is prevented by inducing humoral and cellular immunity, with high antibody titers, that block the parasite from infecting the liver.

- Vaccination with attenuated whole sporozoites has also been reported. For instance, limited clinical trials with volunteers from non-endemic areas demonstrated the development of sterilising immunity in all immunized volunteers after 5 immunizations with irradiated sporozoites administered intravenously.

- It was shown that immunized individuals developed strong antibody responses to sporozoites as well as T cell responses.

- The progressive development of naturally acquired immunity to the erythrocytic stages of falciparum malaria with age has been recognized for many years.

- Some data have suggested that naturally acquired immunity to malaria is primarily dependent on immune responses to parasite-encoded antigens found on the surface of the infected red blood cells rather than on the merozoite.

- Antibodies targeting malaria antigens have been isolated from volunteers immunized with whole parasite vaccine, volunteers immunized with subunit vaccine, individuals from endemic areas as well as mice that have been vaccinated with irradiated sporozoites.

- The contributions of antibodies to this immunity are due in part to a ground-breaking study showing that passive transfer of IgG from adult Africans long exposed to malaria could drive down erythrocytic malaria parasite levels in children with this disease.

- Many blood-stage vaccine candidates have been identified based on studies of mouse malaria parasites, and in some cases protective immunity to these proteins has also been demonstrated in non-human primates.

- In 2018, Kisalu and colleagues reported that several human monoclonal antibodies directed against the Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) circumsporozoite protein (PfCSP) were isolated from several subjects immunized with an attenuated Pf whole-sporozoite (SPZ) vaccine (Sanaria PfSPZ Vaccine).

- They also showed that the passive transfer of one of these antibodies, monoclonal antibody CIS43, conferred high-level, sterile protection in two different mouse models of malaria infection.

- In 2021, Gaudinski and colleagues also showed that administration of the long-acting monoclonal antibody CIS43LS to adults who had never had malaria infection or vaccination prevented malaria after controlled infection.

- The demonstration that CIS43 is highly effective for passive prevention of malaria has potential application for use in travellers, military personnel, elimination campaigns and identifies a new and conserved site of vulnerability on PfCSP for next-generation rational vaccine design.

Quiz

Faculty Presentations:

Download these Resources:

Expand your Knowledge

-

Malaria Vaccine Progress

-

Models for Testing Vaccines

-

Immune Responses to Vaccination

-

Two year old with spiking fevers and depressed level of consciousness – Severe P.falciparum Malaria Case Study

Related Talk

Jeff Dorfman, University of Cape Town – The Immune Mechanisms of Fighting a Malaria Infection

References

- Wells T. and Donini C. 2022. Monoclonal Antibodies for Malaria. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe2208131

- Crompton P.D. et al., 2014. Malaria immunity in man and mosquito: insighs into unsolved mysteries of a deadly infectious disease. Annu Rev Immunol. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120220.

- Kisalu N.K. et al., 2018. A human monoclonal antibody prevents malaria infection by targeting a new site of vulnerability on the parasite. Nat. Med. DOI: 10.1038/nm.4512

- R. Gaudinski M.R. et al., 2021. A Monoclonal Antibody for Malaria Prevention. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034031

- James G. Beeson et al. Challenges and strategies for developing efficacious and long-lasting malaria vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474)

- Wells T. and Donini C. 2022. Monoclonal Antibodies for Malaria. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe2208131

- Crompton P.D. et al., 2014. Malaria immunity in man and mosquito: insighs into unsolved mysteries of a deadly infectious disease. Annu Rev Immunol. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120220.

- Kisalu N.K. et al., 2018. A human monoclonal antibody prevents malaria infection by targeting a new site of vulnerability on the parasite. Nat. Med. DOI: 10.1038/nm.4512

- R. Gaudinski M.R. et al., 2021. A Monoclonal Antibody for Malaria Prevention. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034031

- James G. Beeson et al. Challenges and strategies for developing efficacious and long-lasting malaria vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474)