- The host, via its immune system, has the capacity to recognize materials as foreign to itself and to neutralize, eliminate, or metabolize them with or without injury to its own tissue(s).

- Some of these foreign materials can be referred to as antigens and could be entire micro-organisms like bacteria, fragments of them or substances produced by these micro-organisms.

- This ability to differentiate ‘self’ from ‘nonself’ constitutes the basic hallmark of the immune response and the basis for an understanding of clinical immunology in health and disease.

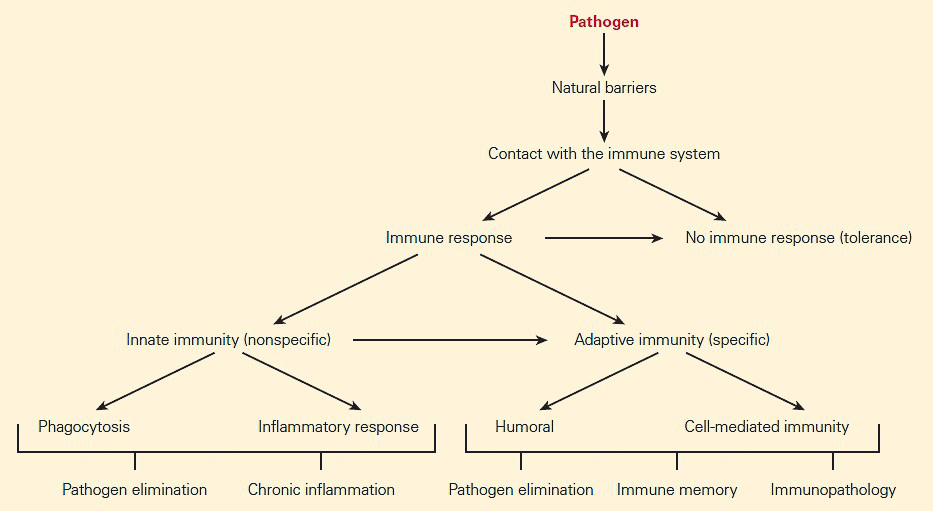

- If the foreign substance cannot be blocked by natural barriers such as skin and mucous secretions, the substance comes into contact with the immune system (Figure 1).

- The mechanisms permitting recognition of foreign structures leading to an immune response can be broken down into two general categories: innate immunity and adaptive immunity.

- The innate and adaptive immune systems both recognize foreign substances by surface receptors on cells of each system. They differ, however, in the genetic control of the synthesis of these receptors.

- The innate immune system uses a relatively large number of germ line genes (102–3) that are already programmed in the genome.

- Although the adaptive immune system utilizes fewer initial inherited preprogrammed genes, they result in an intense expansion (1013–24) through a variety of complex processes involving somatic recombination and mutation.

- The two arms of the immune system work together and should be viewed as interactive and interdependent rather than isolated systems.

- The immune system is part of a broader system, composed of three parts referred to as the neuroendocrine-immune (NEI) network, which represents the interdependent and interrelated responses of the neurological, endocrine, and immunologic systems in response to external and internal stimuli.

Generalities of innate immunity

- The innate immune system is operative on initial and subsequent encounters with foreignness and instructs the type of adaptive immune response that follows.

- One major feature of the innate immune system is that it is taken to be nonspecific, in the sense that anything the body identifies as foreign or non-self is then taken to be a possible target for the innate immune response.

- Several features are known to encompass what forms part of the innate immune system. These include; physical barriers (skin, the gastrointestinal tract, the respiratory tract, the nasopharynx, cilia, eyelashes and other body hair), some of the body’s defence mechanisms (secretions, mucous, bile, gastric acid, saliva, tears, and sweat) and finally the complement pathway.

- When the constitutive anatomical and physiological barriers mentioned above are overcome, an invader next encounters in plasma and tissue fluids a variety of soluble molecules whose immediate activation generates new antimicrobial components that can provide a protective defense. These include molecules from the coagulation (thrombin), fibrinolytic (plasmin), and kinin (bradkinin) cascades, as well as from complement activation (anaphylatoxins C3a, C4a, and C5a, the chemotactic factor C5a, and the opsonizing C3b fragment), which in turn is initiated by the mannose-binding lectin (lectin pathway)

- Complement promotes the inflammatory response, eliminates pathogens through opsonization and lysis (Video 1), and enhances the adaptive immune response. Consequently, deficiencies in complement elements are known to both predispose patients to infection but also can contribute to the pathogenesis of sepsis and immune complex mediated diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Watch video on complement

Reproduced with permission from Bellanti, JA (Ed). Immunology IV: Clinical Applications in Health and Disease. I Care Press, Bethesda, MD, 2012.

- The next defensive component of innate immunity occurs within a period of one to four hours and is provided by the production of a family of signaling molecules that initiates the inflammatory influx and activation of the inflammatory response with major involvement of epithelial cells, endothelial cells, dendritic cells, and mast cells.

- Tissue mast cells (MC), dendritic cells (DC), and macrophages act as guards which continually monitor the microenvironment and respond immediately to homeostatic changes or alterations by releasing various bioactive soluble mediators (cytokines, chemokines, proteases, reactive oxygen species, histamine, prostaglandins, etc.)

- The inflammatory response up-regulates adhesion molecules on endothelial cells of blood vessels and on various phagocytic cells (neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils) which not only leads to the activation of these and other inflammatory cells (mast cells and basophils) and recruitment of cytotoxic cells (NK cells) but also facilitates the migration of some of these cells from the blood into the tissues.

- Activation of these cells by phagocytosis, for example, leads to the rapid secretion of soluble mediators, mainly cytokines, chemokines, oxygen and nitrogen cytotoxic metabolites, and antimicrobial peptides.

- The cellular component of innate immune system recognizes certain structures on a foreign substance—referred to as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that are detected by proteins called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) located on the surfaces of a variety of cells of the innate immune system

Components of the innate immune system

Mononuclear Phagocytes

- Mononuclear phagocytes (monocytes and macrophages) and neutrophils are the phagocytic cells involved in the clearance of inert particles and microbial agents.

- When monocytes are recruited by chemotactic molecules and leave the circulation, they become activated and differentiate into macrophages.

- Other names have been applied to tissue macrophages such as Kupffer cells in the liver, histiocytes in connective tissues, mesangial cells in the kidneys, osteoclasts and chondroclasts in bones and cartilage, alveolar macrophages in the lungs, and microglial cells in the brain.

- In contrast to neutrophils, which are end-stage nonreplicating cells continually replaced from the bone marrow, mononuclear phagocytes can proliferate in situ and are long-lived (i.e., months to years).

- Macrophages actually have a number of important functions in body defense such as:

- Capture by phagocytosis and intracellular killing of microorganisms, infected cells, and tumor cells through PAMP recognition.

- Scavenging of worn-out cells, apoptotic bodies, and other debris potentially harmful to tissues.

- Processing and presentation of antigens for recognition by T cells, expressing co-stimulatory molecules, mainly during secondary adaptive immune responses.

- Releasing cytokines and chemokines that play a major role in innate immune responses.

- Regulate immunity through the alternatively activated pathway.

- The major cytokines produced by macrophages are TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-33.

- Some important systemic effects of cytokines produced by macrophages are fever induced by IL-1, wasting (i.e., cachexia) caused by TNF-alpha, production of acute phase proteins by liver induced by IL-6, and an increase in the maturation and release of neutrophils from bone marrow by IL-3.

- Macrophages also have a role in adaptive responses as antigen-presenting cells and as targets of the effector components of the cellular and humoral adaptive responses, being activated by T cell-derived cytokines and antibodies.

- Macrophage capacity to kill pathogenic microorganisms also can be overcome by microbes that are able to survive inside cells, establishing an intracellular infection, such as Salmonella spp, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Cryptococcus neoformans, or Toxoplasma gondii.

Dendritic Cells

- Dendritic cells (DCs) circulate in the blood prior to migration into epithelial sites of skin and mucosal tissues, where they remain as immature DCs until they come into contact with infectious agents.

- DCs constitute the most efficient antigen-presenting cells for T cell activation, thus linking innate and adaptive immune responses.

- There are different subsets of DCs, most commonly found in the systemic circulation are:

- Plasmacytoid (pDCs), derived from lymphoid precursors.

- Myeloid (mDCs), derived from myeloid precursors.

- A distinguishing feature of pDCs is their capacity to produce large amounts of type I interferons, i.e., IFN-α and IFN-β, during the course of viral infection driven by activation via the endosomal TLR7 and TLR9 pathways.

- mDCs respond best to bacterial infection, recognizing LPS via the cell-surface TLR4 together with the production of IL-12 and TNF-α.

- These cells utilize the mechanisms of pinocytosis (i.e., ‘‘cell-drinking,’’ a form of endocytosis in which small droplets of liquids are brought into the cell suspended within small vesicles) and phagocytosis for the uptake of a wide variety of foreign proteins and infectious agents.

- This results in the activation of DCs during which the maturation of the cells is promoted with the expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7 allowing the cells to migrate from the periphery to secondary lymphoid organs.

- The captured molecules are processed into small peptides, linked to the groove of MHC-II molecules, and expressed on the cell surface of DCs. By the time DCs reach secondary lymphoid organs, they are able to present antigens to naive and memory T cells.

- Activated DCs also produce cytokines of the IL-12 family (IL-12, IL-23, and IL-27) with Th1-cell polarizing capacity and IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β with regulatory T cell polarizing effects.

Mast Cells

- Mast cells (MCs) originate in bone marrow and circulate as CD34+ progenitor cells.

- They are distributed throughout the body, particularly in association with blood vessels, nerves and in close proximity to mucosal surfaces.

- After their development from bone marrow-derived progenitor cells that are primed with stem cell factor (SCF), mast cells continue their maturation and differentiation in peripheral tissue, developing into two well-described subsets of mast cells, MC(T) and MC(TC) on the basis on their enzyme content.

- The TC type predominates in normal skin and intestinal submucosa, and contains tryptase, chymase, a cathepsin G-like protease, and a carboxypeptidase, whereas the tryptase-containing T type MC(T) is found in intestinal mucosa and lung alveolar wall.

- Mast cells recognize microbial PAMPs through TLR1, -2, -4, and -6 and the complement-derived molecules iC3b, and anaphylatoxins (C4a, C3a, and C5a) through their respective receptors.

- After activation, mast cells immediately extrude granule-stored preformed mediators (histamine, tryptase, chymase, and carboxypeptidase) and, in minutes, generate lipid-derived prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), and leukotrienes LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4)

- Late, within hours, they synthesize chemokines (CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5) and cytokines (TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6).

- The rapid release of these mediators promotes vascular permeability, induces vasoconstriction, and recruits eosinophils, neutrophils, and other cells within a very short time (Video 2).

Watch a video of the action of mast cells

Reproduced with permission from Bellanti, JA (Ed). Immunology IV: Clinical Applications in Health and Disease. I Care Press, Bethesda, MD, 2012.

Basophils

- Basophils play a major role in defending the body against multicellular parasites. They have granulocytes characteristics and functions are similar to those described for mast cells.

- Like mast cells, basophils also secrete histamine, making them a key player in mounting an allergic response.

Eosinophils

-

- Eosinophils are another kind of blood granulocyte that can be recruited to sites of innate immune reactions, where their number can be 100 times higher than in the blood.

- Eosinophil cytoplasmic granules contain a variety of cationic proteins that exert several biological effects on normal cells and infectious agents, and these include: major basic protein (MBP), eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN), and eosinophil peroxidase (EPO).

- During the innate immune response, induced by phagocytosis of opsonized particles, the eosinophil granule content is released, acting mainly on extracellular helminthic parasites and contributing to tissue damage in inflammatory diseases.

- Other eosinophil products also participate in acute and chronic inflammatory reactions, particularly in allergic diseases.

Natural Killer Cells

- Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes derived from bone marrow precursors and are found mainly in peripheral circulation, spleen, liver, and bone marrow.

- NK cells have a morphology similar to that of activated cytotoxic lymphocytes, i.e., a large size, an abundant endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and the presence of preformed granules containing perforins and granzymes.

- NK cells includes nonspecific capacity to eliminate target cells, e.g., virus-infected or malignant cells, through apoptosis independently of T or B cells.

- NK cells also stimulate inflammatory responses through secretion of IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, GM-CSF, and chemokines (CCL4, CCL5, CCL22).

- NK cells recognize and kill target cells by apoptosis basically in two ways.

- Some NK cells have killer inhibitory receptors (KIRs) which recognize MHC-I molecules on normal self cells and which, in the normal state, inhibit activation and killing due to the presence in their intracytoplasmatic tail tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs).

- Another diverse set of lectin-type receptors, generically referred to as killer activating receptors (KARs), detect other molecules on altered target cells, e.g., malignant or virus-infected cells, which can provide an activation signal for the NK cell via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs).

- If a target cell has decreased expression of MHC-I, the inhibitory signal from KIR will be decreased, shifting the signal balance towards activation of the NK cell and initiating the process of target cell death by apoptosis.

- NK cells utilize their intracellular granules perforin and granzymes to kill the target cells by inducing apoptosis (Figure 2).

- Upon release, perforin in close proximity to a cell slated for killing, first forms pores in the membrane of the target cell through which the granzymes and associated molecules then enter, inducing apoptosis.

- The second method whereby NK cells kill target cells is through a hybrid mechanism in which the IgG molecule links the innate and adaptive immune systems and is referred to as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC, Figure 2)

- In this scenario, the NK cell recognizes target cells to which IgG antibody has been attached through its Fab regions. The Fc portion of the IgG antibody engages the NK cell through its Fc receptor referred to as CD16 (Fc-γRIII), thus linking the NK cell with the target cell. Following this linkage, the NK cell can destroy the target cells inducing apoptosis.

Some Lymphocytes Behave Like Innate Immune Cells:

Gamma-delta T (γδT) cells

- During thymopoiesis, two major types of mature T cells are generated from a common CD4− CD8− double-negative (DN) precursor: αβT cells and γδT cells, distinguished by the protein chains contained within their TCR complexes.

- γδT cells are the only cells that use somatic rearrangement to generate their antigen receptor repertoire.

- As mature cells, they are a minor population in the peripheral blood (1 percent to 15 percent of total lymphocytes)

- They also play an important role in mucosal immunity, and in viral and bacterial infections.

- γδT cells are implicated in the regulation of immune responses at mucosal surfaces (Chapter 8) and as a first line of defense in host epithelial surfaces in the response against some viruses, bacteria, and parasites before the recruitment of αβT cells.

- Activated γδT cells rapidly produce a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) and chemokines, kill infected and tumor cells using similar cytotoxic effector mechanisms as NK and CD8+ αβT cells, and also behave as APCs through the participation of MHC-I and MHC-II molecules, as well as the co-stimulatory molecules.

Natural Killer T Cells

- NKT cells were originally defined by the co-expression of T cell markers (CD3/TCR complex) along with characteristic surface receptors for NK cells (CD56, CD58, and CD161), indicating a dual nature of this subset. Now, this definition is restricted to a more specific subset, the so-called invariant NKT (iNKT) cells.

- NKT cells can either express or not express CD4 or CD8 molecules and, similar to NK cells, are considered part of the innate immune response because they act swiftly during infections, killing microorganisms or cells and producing cytokines without the need of slower differentiation or proliferative processes as with T and B cells.

- They characteristically express on their surface a TCR invariant or constant region (Vα24/J18/Vβ11 in the human) able to recognize glycolipids presented on CD1d molecules

- The CD1 family (CD1a through CD1d) consists of antigen-presenting molecules encoded by genes located outside of the MHC and structurally similar to the MHC-I molecules.

- In comparison to classical MHC molecules, the CD1 antigen-binding groove is highly hydrophobic and adapted for the presentation of lipid antigens that consist largely of glycolipids.

- The cognate α-galactosylceramide (α-Gal Cer, derived from a marine sponge) is the model glycolipid recognized by iNKT cells.

- iNKT cells are present in internal organs, including the thymus, bone marrow, liver, and spleen.

- There are other populations of cells expressing T and NK membrane markers differing from the iTCR cells, but showing variable TCRs, which are able to recognize a broader set of structures in microorganisms, and these are generically called NKT-like cells.

Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells

- The term MAIT cells came up as a result of landmark studies that showed how mucosal locations such as gut were enriched for these T cells. Further research has gone on to show that within human beings, these cells do have abundant numbers even in non-mucosal tissues, where they account for up to 10% of T-cells in blood.

- They have been placed in the category of as ‘unconventional T-cells’ due to the fact that they recognize non-peptide antigens presented by specialized MHC class I–like molecules

- MAIT cells have also been identified as being restricted to the non-polymorphic MHC class I–like protein MR1.

- They express a semi-invariant TCR (Vα7.2-Jp33 chain), are double negative CD4- and CD8-, recognize hydrophilic antigens presented in MR1 (MHC-I-related) molecules present in B cells, and upon antigen activation, produce IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10.

- MAIT cells have been shown to be implicated in immune responses to TB in the lung.

B-1 Cells

- B-1 cells are a phenotypically and functionally distinct subset of B cells, which spontaneously secrete ‘‘natural’’ IgM antibodies in the absence of any apparent stimulation by specific antigens.

- Accordingly with the expression of CD5 molecules, B-1 cells are subdivided into B-1a that carry the CD5 molecule and B-1b that do not.

- B-1a cells represent the majority of B-lineage cells during neonatal life but decline thereafter.

- The repertoire of natural antibodies is much more restricted than those produced by conventional B cells and a large proportion are poly-reactive to phylogenetically conserved structures such as nucleic acids, heat shock proteins, carbohydrates, and phospholipids.

- The antibodies produced by B-1 cells may participate as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity and make an optimal transition between the two immune responses by producing the first wave of antibodies required for antigenic clearance of viruses, bacteria, and certain parasites.

- Other functions performed by these cells are in the immune regulation through the synthesis of IL-10 and in the clearance of senescent and apoptotic cells.

- It has been suggested that they are also involved in autoimmunity as increases in CD5+ B cell frequency have been reported in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, myasthenia gravis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Marginal zone B (MZ B) cells

-

- MZ B cells are a rare non-recirculating subset of mature peripheral B cells exclusively located in the spleen, different from the more abundant recirculating follicular B cell subset.

- The MZ B cell population is separated from the B cell follicle by the marginal sinus.

- MZ B cells express high levels of CD1d and CD21 molecules.

- They are quick and easily activated by low levels of antigen, are potent antigen-presenting cells for naive T cells, and produce short-lived IgM antibody-forming cells involved in the early defense against blood-borne pathogens, as well as in autoreactive B cell responses.

Generalities of Adaptive Immunity

- The second major branch of the immune system includes a complex set of genetically controlled, interdependent, and interactive responses referred to as adaptive or acquired (specific) immune responses.

- Adaptive immune system characterized by:

- Specificity: The recognition of the foreign substance (i.e., antigen or immunogen) by antigen-recognition molecules on the surface of lymphocytes in a highly precise and selective manner.

- Heterogeneity: The cells and cell products that comprise the adaptive immune system consist of a variety of different types.

- Memory: The ability to recognize an antigen upon subsequent encounters with the foreign substance in a more rapid and highly augmented fashion.

- Because the adaptive immune system is composed of relatively small numbers of cells with specificity to recognize an individual immunogen, the responding cells must proliferate, forming a cell clone, and differentiate into effector cells after encountering a foreign substance.

- Adaptive immune response produces large quantities of long-lived cells (i.e., memory cells, as described below) that persist in an apparently dormant state, but that can re-express effector functions rapidly after subsequent encounters with the same antigen.

- The two major components of the adaptive immune response are (1) humoral immunity and (2) cell-mediated immunity (CMI).

- Humoral immunity is a process carried out by proteins called antibodies that belong to the family of immunoglobulins, produced by a subset of lymphocytes (B cells) in response to and capable of reacting with antigen. These antibodies specifically bind extracellular antigen.

- In humans, there are five major classes (i.e., isotypes) of immunoglobulins: IgM, IgG, IgA, IgD, and IgE, each differing in physical, chemical, and biologic properties.

- Cell-mediated immunity is the other arm of the adaptive immune response carried out by another subset of lymphocytes referred to as T lymphocytes.

- T cells are capable of recognizing intracellular infections (viruses and bacteria that can survive inside the cells that have ingested them).

- Cell-mediated immunity is a process carried out by T cells through the production of cell-regulating molecules (cytokines) or through inducing cell death (cytotoxicity) without the participation of antibody.

Elements of Adaptive Immunity

T Lymphocytes

- T lymphocytes are identified by a surface cluster of differentiation (CD) molecule named CD3 and are comprised of two major groups: the CD4 and CD8 populations.

- The CD4 cells display helper activities on other populations of cells, and in turn are subdivided into Th1, Th2, a T regulatory (Treg) group, and, in addition, a recently described T cell subset called Th17, each with a characteristic profile of production of proinflammatory cytokines.

- The CD8 T cytotoxic population functions in killing target cells; they are comprised of Tc1 and Tc2 subpopulations with similar cytokine profiles as Th1 and Th2 cells.

- T lymphocytes facilitate promotion of inflammation by cytokine production (Th1 and Th17 cells), help B lymphocytes (Th2 cells), regulate immunosuppressive responses (T regulatory cells), and kill unwanted target cells (Tc1 and Tc2 cells).

- The role of T lymphocytes is to deal with intracellular infections and “altered self” cells (tumor cells)

- Following the uptake and digestion by APCs, foreign substances, usually proteins, are processed by proteolysis into peptide fragments that are later presented to T cells in a highly discriminative manner.

- This process employs cell receptors consisting of molecules on both the surface of the APC membrane (i.e., MHC proteins) as well as a specific antigen-binding receptor on the T cell membrane, the TCR.

B Lymphocytes

- B lymphocytes are those cells that ultimately respond to environmental immunogens (or antigens) with the production of protein molecules identified as immunoglobulins, which function as antibody and which can react specifically with antigen.

- Because these effector molecules circulate in the blood and tissues, they were designated by the ancient term “humors” and were assigned a role in humoral immunity, in contrast to those carried by cells, i.e., cell-mediated immunity.

- The synthesis of these molecules occurs in the terminally differentiated form of the B cell, the plasma cell, with the collaboration of the Th2 helper lymphocyte.

- B cells can also serve as APCs.

- The cell surface immunoglobulins of the B cell that recognize antigen consist of monomeric IgM and IgD.

- As a consequence of the binding of antigen with the BCR, four processes are triggered: (1) antigen processing and presentation to CD4+ cells, which in turn enhance the activation of B cells; (2) B cell proliferation and differentiation, primarily in germinal centers of the spleen or lymph node into clones of antibody-secreting plasma cells; (3) each of which secretes immunoglobulins that are specific for the antigen; and (4) memory formation.

Quiz