Natural Killer (NK) Cells

- NK cells are one of the members of the innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) family. NK cells share characteristics with both, innate and adaptive immune cells such as a rapid responsiveness (innate), cytotoxic potential and memory (adaptive). They are also considered as a nexus or bridge between the innate and adaptive immune system.

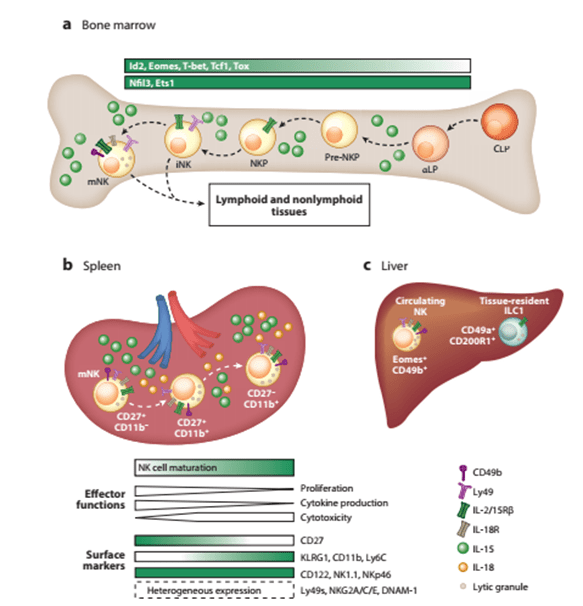

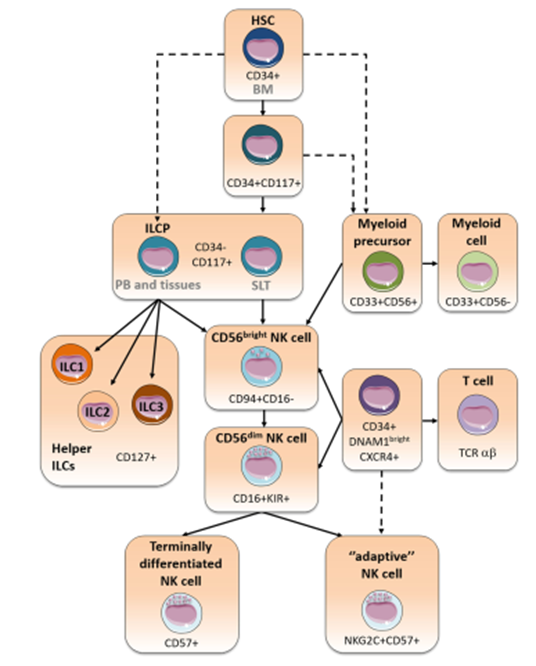

- NK cell development occurs in the bone marrow (BM) from common lymphocyte progenitors (CLP) and their development depends on IL-15, which induces the expression of transcription factors such as Nfil3, Id2 and Eomesodermin (Eomes). IL-15 is also involved in their survival and innate effector functions by regulating their metabolism. After their early stages of development, NK cells continue their maturation in the BM and then in the periphery, expressing different transcription factors, surface and effector molecules. Mature NK cells can be found in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs like peripheral blood (PB), a characteristic that distinguishes them from other ILCs.

- Mature NK cells in mice are characterized by the expression of NK1.1+CD3– NKp46+ Tbet+ Eomes+ CD49b+. CD11b+ CD27– NK cells are considered the most mature NK cells in mice and represent the majority (~90%) of NK cells in PB. These NK cells have a high cytotoxic potential and IFN-y production after target cell recognition.

Mature NK cells in humans can be divided into 2 types:

- CD56dimCD16+: highly cytotoxic NK cells predominantly found in PB

- CD56brightCD16+: high cytokine production capacity, predominantly found in secondary lymphoid tissues.

NKP, NK cell progenitor. [Source: Adriana M. Mujal et al., 2021]

- Mature NK cells are involved in strong anti-tumor responses and also represent the first line defense against viral infections. The mechanisms responsible for a protective immune response brought about by NK cells are diverse and include: high cytotoxic potential, production of inflammatory cytokines (IFN-y and TNF) and also death receptor ligation (FAS-FASL).

Adaptive/memory NK cells

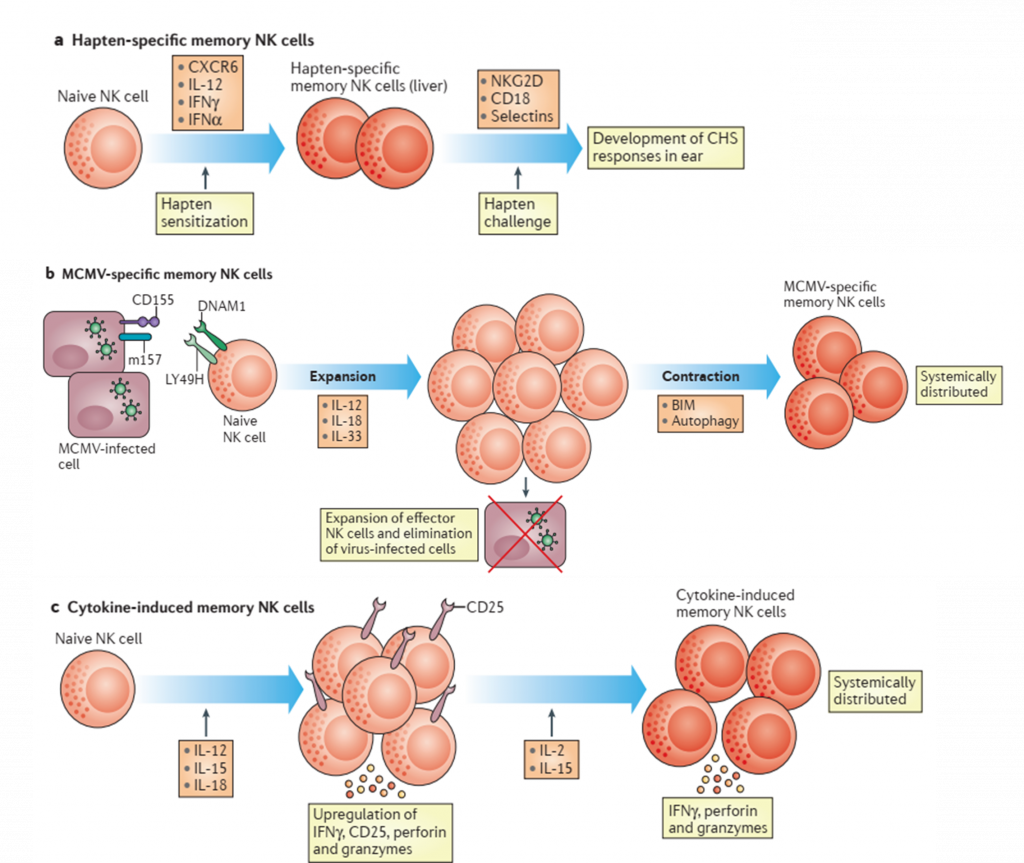

- Recently the concept of “trained immunity” or “innate immune memory” has been reported and it refers to the ability of innate immune system to take on characteristics of the adaptive immune system In both human and mouse models, NK cells have demonstrated immunological memory after encountering some viruses or inflammatory cytokine milieux.

- Memory NK cells in mouse models

- It has been reported that mice lacking B and T cells develop contact hypersensitivity (CHS) after hapten sensitization. CHS, however, did not develop in these mice after depletion of NK cells using NK1.1 antibodies (Ab). Also, this response has been demonstrated to be sensitization-dependent and hapten-specific.

- Specific memory NK cells have also been reported in some virus models like mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV)

- RAG2-deficient mice adoptively transferred with In-vitro IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18 stimulated NK cells in absence of a defined antigen, has been able to generate NK cells that respond with sustained IFN-y production after IL-12 and/or IL-15 in-vivo stimulation.

- The receptors driving the generation of memory NK cells in mice remain unclear.

- Memory NK cells in mouse models

-

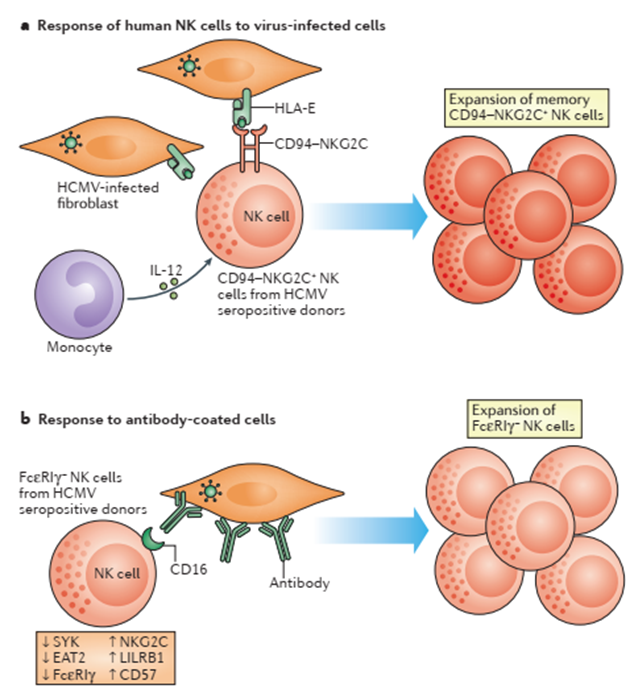

- Memory NK cells in humans

- Memory NK cells have been reported in individuals who have previously encountered human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). These memory NK cells have been defined by the expression of activation CD94-NKG2C receptor.

- In-vitro experiments have demonstrated CD94-NKG2C+ NK cells expansion after the CD94-NKG2C receptor interacts with its ligand HLA-E. This expansion also has been reported after cell-cell contact with infected cells and soluble factors.

- Memory NK cells in humans

- As has been mentioned “innate immune memory” cells are characterized by their ability to rapidly expand and respond by increasing production of effector molecules after a re-encounter with a pathogen. Memory NK cells have been demonstrated to produce higher levels of IFN-y in comparison to naïve NK cells after MCMV re-infection but not with heterologous pathogens in mouse models. Another characteristic that distinguishes memory NK cells from naïve NK cells are the stable epigenetic changes. The expansion of CD94-NKG2C human NK cells and their robust cytotoxic response has been reported in HCMV-seropositive individuals. These cells also exhibited epigenetic changes such as a demethylated CNS1 region in the IFNG locus.

Quiz

Download these Resources:

References

- Quatrini, L., Della Chiesa, M., Sivori, S., Mingari, M.C., Pende, D. and Moretta, L. (2021), Human NK cells, their receptors and function. Eur. J. Immunol., 51: 1566-1579. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.202049028

- Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016 Feb;16(2):112-23. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.9. Epub 2016 Jan 25. PMID: 26806484.

- Mujal A, Delconte R, Sun J. Natural Killer Cells: From Innate to Adaptive Features. Annual Review of Immunology 2021 39:1, 417-447

References

- Quatrini, L., Della Chiesa, M., Sivori, S., Mingari, M.C., Pende, D. and Moretta, L. (2021), Human NK cells, their receptors and function. Eur. J. Immunol., 51: 1566-1579. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.202049028

- Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016 Feb;16(2):112-23. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.9. Epub 2016 Jan 25. PMID: 26806484.

- Mujal A, Delconte R, Sun J. Natural Killer Cells: From Innate to Adaptive Features. Annual Review of Immunology 2021 39:1, 417-447