SARS-CoV-2 origin and transmission

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) first identified in December 2019, is the etiological agent of coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

- SARS-CoV-2 has zoonotic origin and shares genomic similarity with other zoonotic viruses responsible for SARS (SARS-CoV-1) and MERS (MERS CoV EMC/2012).

- The discovery that its closest identified viral relatives are enzootic in horseshoe (Rhinolophus) bat indicates that SARS-CoV-2 probably emerged from an as-yet-unidentified bat reservoir either directly or after infection of an intermediate host such as a pangolin (Morens et al. 2020).

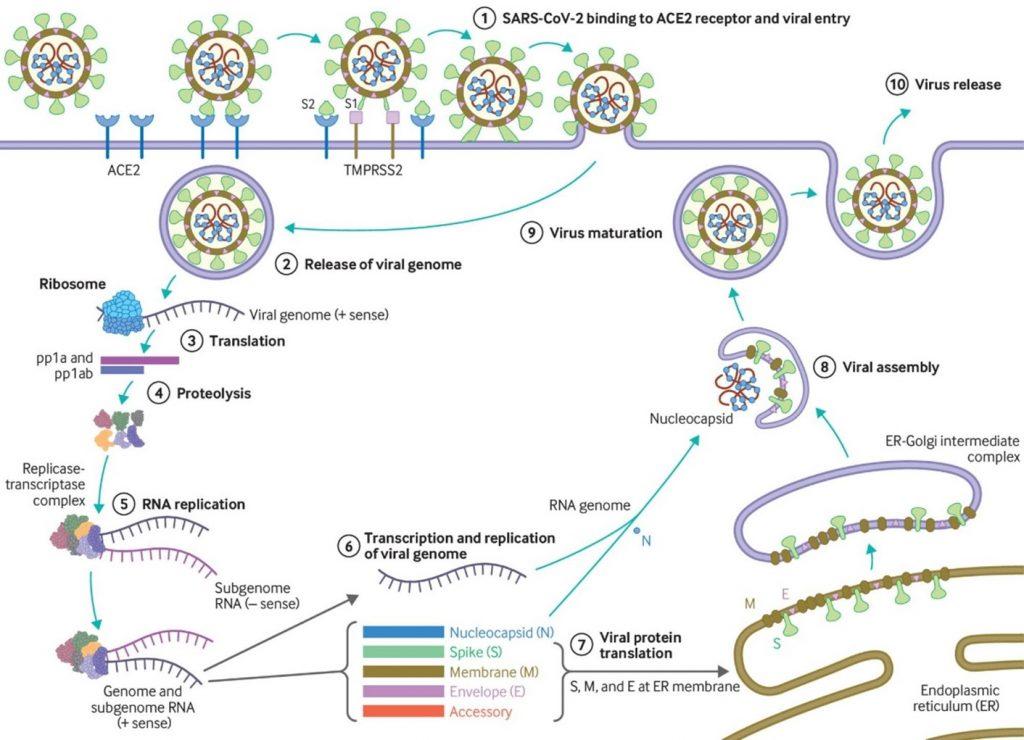

- SARS-CoV-2 has a receptor binding domain (RBD) in the spike (S) protein consisting of 6 amino acids which not only differentiates it from SARS- CoV-1 but also confers it with ability to bind human or human-like Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE2) with high affinity (Figure. 1).

- SARS-CoV-2 also has a polybasic furin cleavage site on the highly variable spike protein which is also unique to SARS-CoV-2. This site allows cleavage by proteases and determines viral host range and is potentially associated with increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.

- SARS-CoV-2 is airborne, thus wearing a mask remains one of the most effective precautionary measures for preventing acquisition of the virus

SARS-COV-2 Pathogenesis

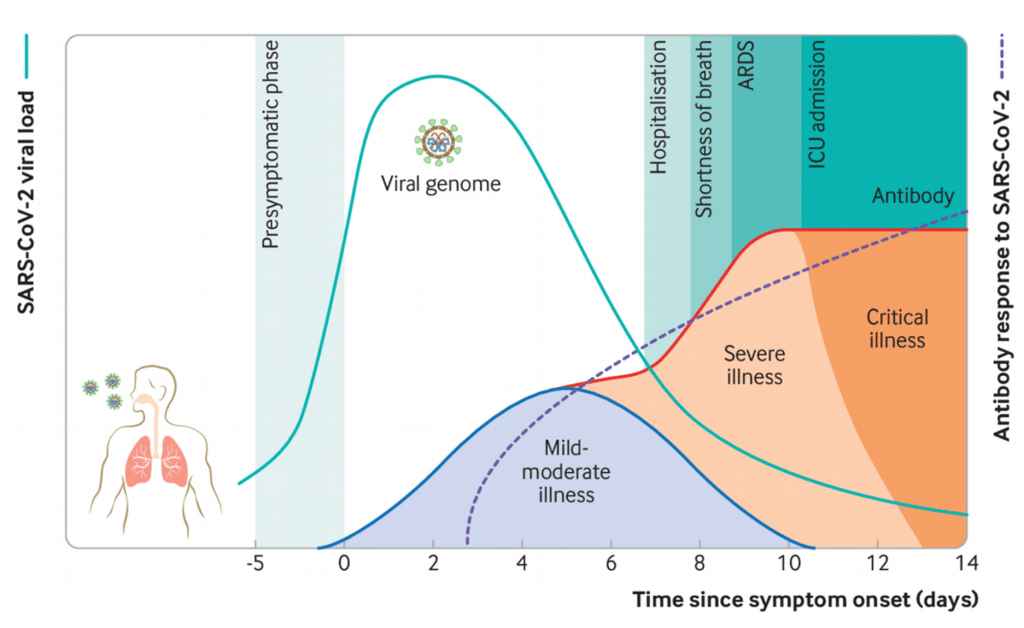

- SARS-CoV-2 causes a broad-spectrum of diseases ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe symptomatic disease (Figure 2). Most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic or develop mild symptoms as fever, cough, myalgia, headache, and taste and smell disturbance.

- Severe COVID-19 is associated with excessive levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines due to unregulated immune response defining a cytokine storm syndrome which leads to more tissue damage even when viral load is low. IL-6 and TNFα serum levels have been shown to be significant predictors of disease severity and death (Del Valle et al. 2020).

- Additionally, individuals with severe COVID-19 can also develop complications such as thrombosis, sepsis and multi-organ dysfunction.

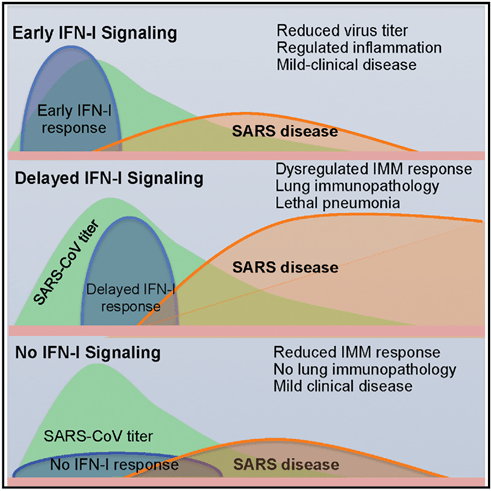

- Robust virus replication accompanied by delayed type I interferon (IFN-I) signalling orchestrates inflammatory responses and lung immunopathology with diminished survival (Figure. 3). This delayed IFN-I signalling promote the accumulation of pathogenic inflammatory monocyte macrophages resulting in elevated lung cytokine/chemokine levels, vascular leakage, and impaired virus-specific T cell responses.

- Infection induces robust antibody and T cell responses, which in most cases likely controls viremia before COVID-19 pathogenesis progressors.

- Studies have shown that although circulating SARS-CoV-2-specific Ab and T cell responses may wane quickly, natural infection (and potentially vaccination) induces long-lasting memory B cell immunity which persists despite a decline in circulating SARS-CoV-2-antibodies.

COVID-19 vaccines

- There have been multiple COVID-19 vaccine candidates with a variety of platforms that have been tested in pre-clinical and clinical trial settings, some of which are highlighted in Table 1.

- Approved vaccines have been through randomized clinical trials to test their quality, safety and efficacy. To be approved, vaccines are required to have a high efficacy rate of 50% or above.

- mRNA vaccines (mRNA-1273, BNT162b2) and Sputnik V (viral vector; Gamaleya) demonstrated over 90% efficacy against SARS-CoV2 infection, while other viral vector vaccines (Ad26.COV2.S and AZD1222) didn’t perform as well with efficacies above 70%. The first protein subunit COVID-19 vaccine to become available Novavax showed a 89% efficacy.

- The duration of vaccine protection is still being studied. A gradually declining trend in vaccine protection against infection have been suggested. For BNT162b2, the 95% efficacy number down to 84% after 6 months. The effectiveness of vaccines against infection after 6 months decreases in a variable way depending on the variants, for example for the delta: the effectiveness of Pfizer falls to 42% while that of Moderna is 76% (Puranik et al, 2021)

- Single-shot booster doses of BNT162b2 vaccine are recommended by CDC at least six months after completion of the primary doses for those over 65, people with underlying medical conditions and healthcare professionals. Booster shots for other vaccines are suggested.

Table 1. COVID-19 Vaccines

[table id=253 /]

* Vaccine candidates in phase 3 clinical trials and not yet approved for use by WHO.

Interested in learning more about COVID-19 vaccines? Read the following news summaries:

- COV2.S is safe and immunogenic

- Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine

- BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy results

- Safety and immunogenicity of Sputnik V vaccine

- Viral genomic analysis of breakthrough infections (infection in fully vaccinated individuals) highlighted the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants (discussed in detail below) which significantly lowered efficacy signal of Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and AZD1222 (Oxford/Astra-Zeneca), while other vaccine mRNA-1273 (Moderna), BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) and Sputnik V (Gamaleya) were tested when the original SARS-CoV-2 variant was still the most prevalent.

- Approved vaccines have been shown to induce robust vaccine induced humoral and cellular immunity and are very efficacious against severe COVID-19 which may require hospitalization or even lead to mortality.

Heterologous prime-boost vaccination

- Due to limited global access to COVID-19 vaccines, largely resulting in vaccine inequity in Asia and Africa. Researchers are investigating novel vaccination strategies, such as heterologous prime-boost strategies to facilitate mass COVID-19 vaccinations.

- As the different platforms differ in efficacy, duration of protection, and side effects, heterologous prime-boost vaccination can maximize the benefits of vaccination.

- In light of concerns regarding thrombotic thrombocytopenia after the first dose of AZD1222, several countries are now advising that individuals previously primed with this vaccine should receive an alternative vaccine as their second dose, most commonly mRNA vaccines such as the BNT162b2.

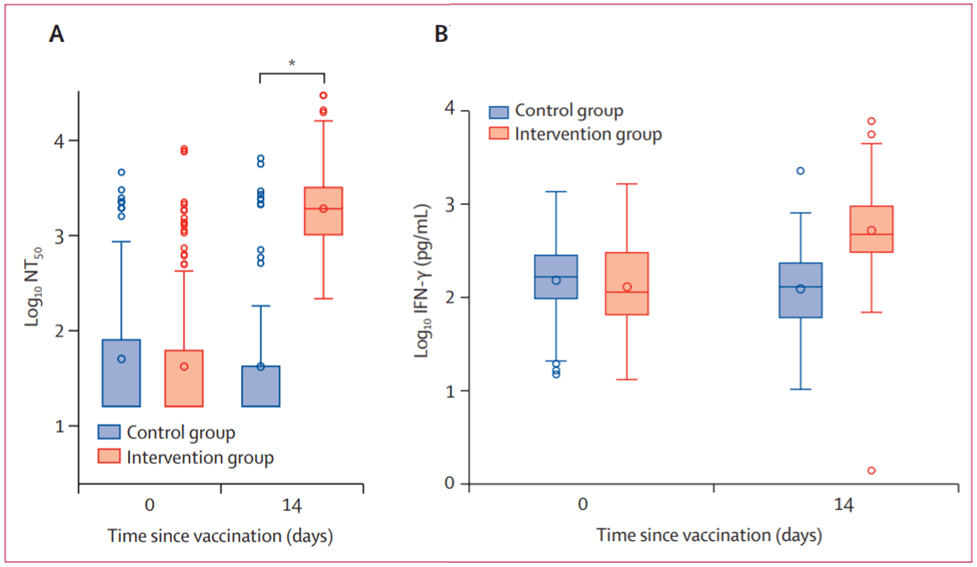

- In a phase 2 trial testing, Borobia et al. demonstrated that BNT162b2 given as a second dose in individuals vaccinated with AZD1222 induced a robust immune response, with an acceptable and manageable reactogenicity profile. Additionally immune responses in the heterologous vaccination arm had significantly higher levels than control vaccination arm (Figure. 4)

Correlates of protection: Neutralizing antibodies

- Correlates of protection define the immune responses that are statistically associated with protection against disease.

- Due to limited knowledge of what protective immune responses are associated with prevention of COVID-19, majority of COVID-19 vaccines were tested without knowledge of the correlates of protection of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Neutralizing antibodies are often considered potential correlates of protection against viruses; thus majority of natural SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity studies measure the induction of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) as one of the trial endpoints. However, are Abs truly correlate of SARS-CoV-2 protection?

- A large number of NAbs have been identified, and some have been shown to reduce the viral load in patients with COVID-19. The level of IgG against the S protein RBD was demonstrated to be correlated with SARS-CoV2-neutralizing activities in the sera from COVID-19 patients.

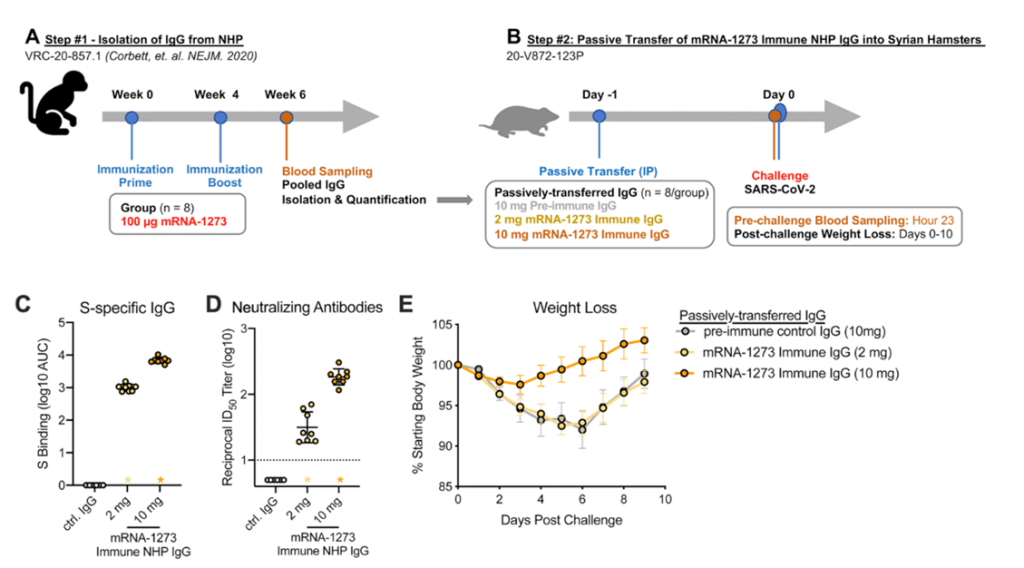

- Results from non-human primates suggest mRNA-1273 vaccine induced Abs detectable in serum and localized at mucosal sites can restrict SARS-CoV-2 replication and confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection (Corbett et al., 2021). Further passive transfer of vaccine-induces IgG in naïve hamsters was sufficient for protection (Figure 5).

- High levels of protection were noted after vaccination with one dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine, despite modest levels of neutralizing antibody, strongly supporting the concept that other mechanisms are at play as co-correlates of protection.

Correlates of protection: Cellular response

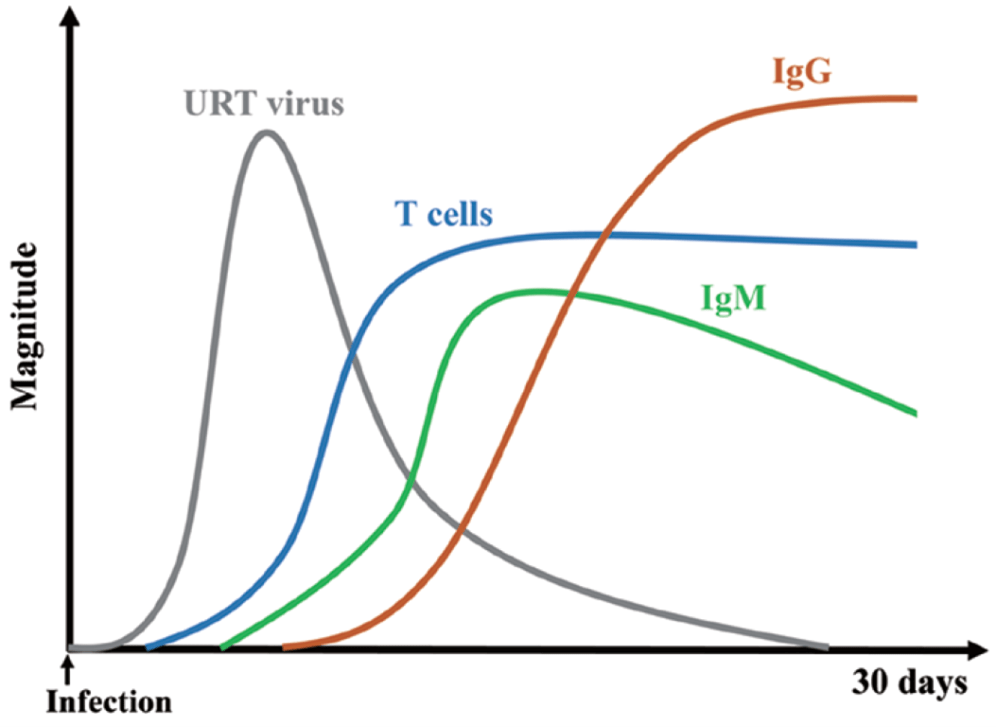

- Following natural SARS-CoV-2 infection, T-cell responses are rapidly activated (Figure 6).

- Virus-specific T-cell responses have been shown to be associated with milder disease in COVID-19 patients. The involvement of T cells is also critical for B-cell maturation and the induction of strong and durable antibody responses. Therefore, the generation of a robust cellular immune response is a desirable attribute for a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.

- It is considered advantageous if a COVID-19 vaccine activates type 1 helper T-cell (Th1)-skewed T-cell responses or balanced T-cell responses. Th2-skewed responses have raised safety concerns about the potential for vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (ERD) in previous experience with coronavirus vaccines.

- mRNA vaccines elicited Th1-biased T-cell responses were induced and were characterized by expression of IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2 but very low levels of IL-4 with minimal Th2 cytokine expression (IL-4 and IL-13).

- In addition, S-specific IFNγ +CD8+ T cells were also robustly induced by BNT162b2. Another mRNA vaccine, mRNA-1273, elicited low levels of SARS-CoV-2 S-specific CD8+ T-cell responses.

- Humoral and cellular responses were induced by DNA and all viral vectored vaccines for which data have been published.

- Inactive virus vaccines show lower cellular responses. Zhang et al. showed that boosting with either recombinant subunit, adenovirus vectored or mRNA vaccine after two-doses of inactivated vaccine further improved both neutralizing antibody and Spike-specific Th1-type T cell responses compared to boosting with a third dose of inactivated vaccine.

A summary of data published on humoral and cellular responses of COVID-19 vaccines can be found in this article by Xu et al.

Natural VS Vaccinal protection:

- A recent CDC study found that 36% of COVID-19 cases didn’t result in development of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. These people presented with different levels of illness from asymptomatic infection to severe COVID-19. Subsequently, a third of people who get COVID-19 don’t develop appropriate protection from reinfection.

- Natural immunity seems to fade more quickly than vaccine immunity as a CDC study reported that 94% of previously infected people experienced a decline in SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after 60 days and 28% among them seroreverted to below the threshold of positivity. mRNA vaccine protection seems to last longer, up to at least six months.

- Gazit et al. demonstrated that natural immunity confers longer lasting and stronger protection against infection, symptomatic disease and hospitalization caused by the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, compared to the BNT162b2 two-dose vaccine-induced immunity.

- Natural immunity alone is weak. After a SARS CoV-2 infection, unvaccinated people are 2.34 times likelier to get COVID-19 again, compared to fully vaccinated people. So after infection, vaccinated people have half the risk of reinfection than people relying on natural immunity alone. Thus, the vaccine gives a booster response to the natural infection.

SARS-CoV-2 Immune escape: Effect of SARS-CoV-2 variants on pre-existing immune responses

- Viruses are known to naturally mutate without impacting the ability of the virus to cause infection nor diseases. However, if mutations occur cumulatively in proteins that are required for viral entry or in epitopes targeted by immune responses this may impact transmissibility or diseases severity of the mutated virus.

- SARS-CoV-2 has evolved more rapidly than researchers anticipated, resulting in the evolution of multiple variants (viruses with one or multiple mutations distinct from the initial detected SARS-CoV-2 strain). These variants have been designated as variants of concern (VOC) and variants of interest (VOI).

- VOI present with genetic changes that are predicted to affect virus characteristics such as transmissibility, disease severity, immune escape, diagnostic or therapeutic escape. VOI have an epidemiological impact as they cause significant community transmission or multiple COVID-19 clusters.

- VOC are VOI that has been demonstrated to be associated with an Increase in transmissibility or in virulence, a change in clinical disease presentation, or a decrease in effectiveness of social measures or available diagnostics, vaccines, therapeutics.

- Recently a new class of variants was added designated as Variants Being Monitored (VBM). A previously designated VOI or VOC that has conclusively demonstrated to no longer pose a major added risk to global public health, can be reclassified as VBM.

- As of 6th October 2021, 4 VOCs were identified by the WHO (Table 2).

Table 2: SARS-CoV-2 Variants of interest

[table id=248 /]

Source: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

- New SARS-CoV-2 variants, emerged in the UK (501Y.V1, B.1.1.7 lineage), South Africa (501Y.V2, B.1.351 lineage) and Brazil (501Y.V3, P.1 lineage), were spreading globally and were found to escape neutralization induced by virus infection and vaccination.

- It was demonstrated that S protein E484K found in B.1.1.7, B.1.351 and P.1 variants, was a key mutation that resulted in variant virus resistance to the neutralizing activity of most NAb engaging the RBD, convalescent sera and mRNA vaccine-induced immune sera.

- Plasma from persons infected with the original variant showed substantially lower neutralization of the B.1.351 variant than of the original variant. Interestingly, the reverse experiment showed immune responses induced by the B.1.351 variant conferred cross-reactive immunity against both the original variant and P.1 (Moyo-Gwete et al., 2021). This cross reactivity suggests that developing vaccines that include known mutations in the VOC may increase the efficacy of vaccines.

- T cells in infected or vaccinated individuals can also elicit robust and cross-reactive immune responses against VOCs. Tarke et al. demonstrated that T cells of exposed donors or vaccinees effectively recognize SARS-CoV-2 variants and 93% and 97% of CD4 and CD8 epitopes are 100% conserved across variants.

Quiz

Download these Resources:

The impact of structural bioinformatics tools and resources on SARS-CoV-2

1 file(s) 878.21 KB

References

- Altman et al., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants: Subversion of antibody response and predicted impact on T cell recognition. Cell Reports Medicine

- Andersen et al., The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine

- Borbia et al., 2021. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 booster in ChAdOx1-S-primed participants (CombivacS) a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet

- Cevik et al., 2020. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ

- Channappanavar R et al., 2016. Dysregulated Type I Interferon and Inflammatory Monocyte-Macrophage Responses Cause Lethal Pneumonia in SARS-CoV-Infected Mice. Cell Host Microbe

- Corbett et al,. 2021. Immune correlates of protection by mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman primates. Sience

- Dan et al., 2020. Immunological memory to SARS-Cov-2 assessed for upto 8 months after infection. Science

- Del Valle et al., 2020. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nature

- Feng et al., Pre-print. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv

- Gazit et al.,2021. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 natural immunity to vaccine-induced immunity: reinfections versus breakthrough infections. MedRxiv and BioRxiv

- Gilbert et al., Pre-print. Immune Correlates Analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. MedRxiv

- Greenhalgh et al., 2021. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet

- Hartley et al., 2020. Rapid generation of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence. Science

- Madhi et al., 2021. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. NEJM

- Morens et al., 2020. Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19. CELL

- Moyo-Gwete et al., 2021. Cross-Reactive Neutralizing Antibody Responses Elicited by SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 (B.1.351). NEJM

- Puranik et al., 2021.Comparison of two highly-effective mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 during periods of Alpha and Delta variant prevalence. medRxiv .

- Singh & Yi. 2021. On the origin of SARS-Cov2. EMM

- Tarke et al., 2021 Impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on the total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell reactivity in infected or vaccinated individuals. Cell reports Medicine

- Tergally et al., 2021. Sixteen novel lineages of Sars Cov2 in South Africa.Nature Medecine

- Vicek et al., 2020. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS- CoV-2. BMJ

- Wang et al., 2021. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature

- Wibmer et al., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nature Medicine

- Xu et al,. 2021. Humoral and cellular immunity and the safety of COVID-19 vaccines: a summary of data published by 21 May 2021. Int Immunol.

- Also read COVID-19 related articles on the Breaking News page

References

- Altman et al., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants: Subversion of antibody response and predicted impact on T cell recognition. Cell Reports Medicine

- Andersen et al., The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine

- Borbia et al., 2021. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 booster in ChAdOx1-S-primed participants (CombivacS) a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet

- Cevik et al., 2020. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ

- Channappanavar R et al., 2016. Dysregulated Type I Interferon and Inflammatory Monocyte-Macrophage Responses Cause Lethal Pneumonia in SARS-CoV-Infected Mice. Cell Host Microbe

- Corbett et al,. 2021. Immune correlates of protection by mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman primates. Sience

- Dan et al., 2020. Immunological memory to SARS-Cov-2 assessed for upto 8 months after infection. Science

- Del Valle et al., 2020. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nature

- Feng et al., Pre-print. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv

- Gazit et al.,2021. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 natural immunity to vaccine-induced immunity: reinfections versus breakthrough infections. MedRxiv and BioRxiv

- Gilbert et al., Pre-print. Immune Correlates Analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. MedRxiv

- Greenhalgh et al., 2021. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet

- Hartley et al., 2020. Rapid generation of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence. Science

- Madhi et al., 2021. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. NEJM

- Morens et al., 2020. Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19. CELL

- Moyo-Gwete et al., 2021. Cross-Reactive Neutralizing Antibody Responses Elicited by SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 (B.1.351). NEJM

- Puranik et al., 2021.Comparison of two highly-effective mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 during periods of Alpha and Delta variant prevalence. medRxiv .

- Singh & Yi. 2021. On the origin of SARS-Cov2. EMM

- Tarke et al., 2021 Impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on the total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell reactivity in infected or vaccinated individuals. Cell reports Medicine

- Tergally et al., 2021. Sixteen novel lineages of Sars Cov2 in South Africa.Nature Medecine

- Vicek et al., 2020. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS- CoV-2. BMJ

- Wang et al., 2021. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature

- Wibmer et al., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nature Medicine

- Xu et al,. 2021. Humoral and cellular immunity and the safety of COVID-19 vaccines: a summary of data published by 21 May 2021. Int Immunol.

- Also read COVID-19 related articles on the Breaking News page