- Cancer immunotherapy has achieved a key role in the history of cancer therapy. The fact that genetic and cellular dysregulations in cancer provide the immune system the opportunity to generate T cells responses to eradicate tumor cells that express “neoantigens” has changed the cancer treatment paradigms by the revolutionizing discoveries in this field, including monoclonal antibodies, cancer vaccines, cell-based therapies, and immune checkpoint blockers.

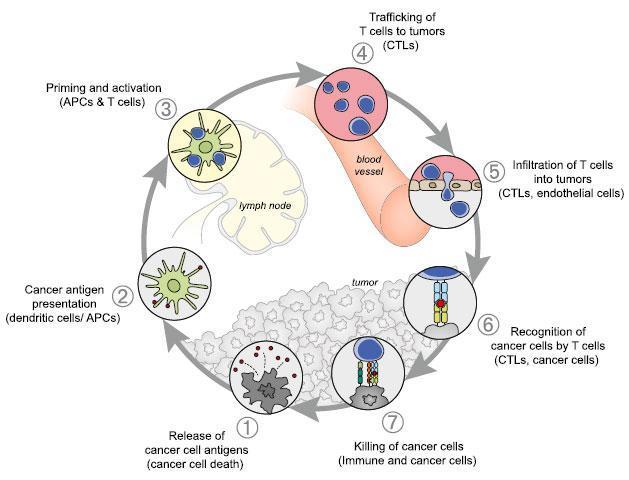

- For an effective anticancer immune response, the neoantigens are released by tumor cells and then captured by dendritic cells (DCs) for processing.

- DCs present the captured antigens on major histocompatiblity class (MHC) I and MHC II molecules to T cells, resulting in the priming and activation of effector T cell responses against cancer antigens.

- Some signals like proinflammatory cytokines and factors released by dying tumor cells or gut microbiota are important to set an appropriate immune response. In addition, the ratio of T effector cells vs T regulatory cells will determine the outcome.

- The activated effector T cells traffic to the tumor to recognize and bind to cancer cells through the interaction between TCR and its cognate antigen for further elimination.

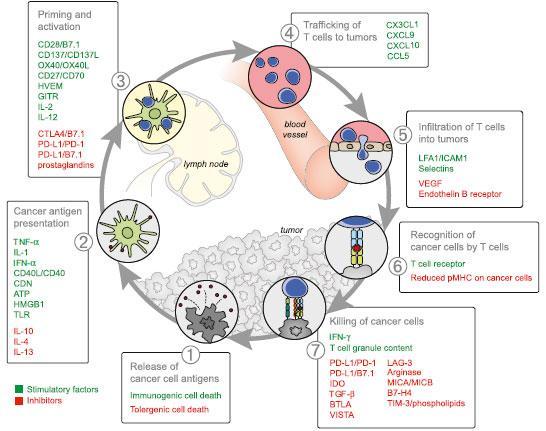

- The “cancer immunity cycle” is tightly regulated by stimulatory and inhibitory factors that could be expressed on the surface of tumor cells or released to the microenvironment.

- For example, the immune rheostat (“immunostat”) factors, such as PD-L1, can have an inhibitory function that modulates an active immune response in the tumor; other factors that have been identified are: TIM-3, MICA/MICB, CTLA4, reduced pMHC on cancer cells, among others.

- The goal of cancer immunotherapy is to initiate or reinitiate a self-sustaining cycle enabling it to amplify and propagate a successful immune response against the tumor.

- The discovery and development of monoclonal antibodies against the inhibitory immune checkpoints CTLA-4 and PD-1 have resulted in dramatic antitumor response by the upregulation of immune activation at various stages of the cancer immune cycle.

- The therapy based in immune checkpoint inhibitors are now indicated in different types of neoplasia’s, including melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, merkel cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Table 1. Indications for immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced-stage cancers, as currently approved by Health Canada

[table id=243 /]

Table 1. Indications for immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced-stage cancers, as currently approved by Health Canada. [Esfahani et al. 2020. A review of cancer immunotherapy: from the past, to the present, to the future]

NSCLC = non-small-cell lung cancer; RCC = renal cell carcinoma (clear cell); SCCHN = squamous-cell carcinoma of head and neck; Tx = treatment; ASCT = autologous stem-cell transplantation; CTxRT = chemoradiotherapy.

- Some clinical trials are assessing the potential of other agonistic or inhibitory checkpoints to affect the tumor outcome. It’s worth mentioning that numerous side effects have been described, for example, the CD28 antibody resulted in cytokine syndrome that leads to hospitalization.

- Immunotherapies are limited by their immune related adverse events (IRAES) which consists the immune activation and inflammatory response against the host’s healthy tissues. For IRAES, the guidelines recommend broad immunosuppression consisting of corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and T cell suppressants.

- This strategy of modulating cytokines is a double edged sword because some soluble factors such as TNF-α and IL-17 are called pleiotropic cytokines with a dual role in immunity because either promote tumour surveillance or can be mediators of autoimmune reactions.

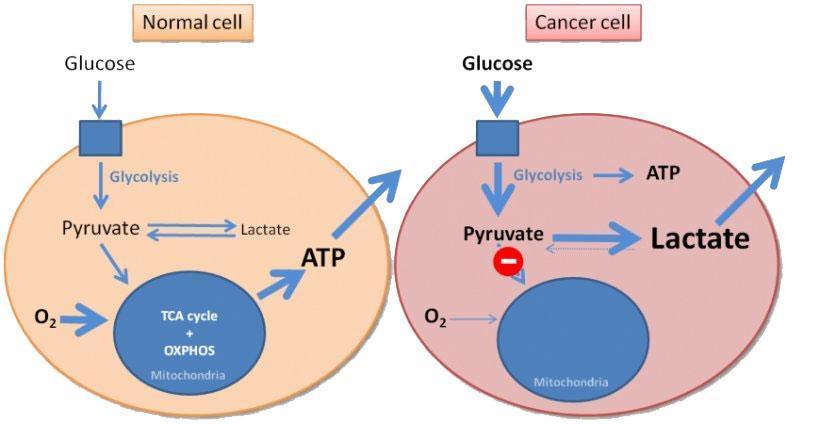

- Another field that has been extensively studied is the relationship between antitumor immune response and tumor metabolism. There is growing evidence that the tumor microenvironment supports inappropriate metabolic reprograming that negatively affects the T cell function. Tumor cells are metabolically dynamic with a high glycolytic activity, better known as “Warburg Effect” which is recognized as one of the hallmarks of carcinogenesis.

- Tumor cells block the access of T cells to nutrients that are necessary for their activation and generate high levels of lactate. The lack of nutrients and accumulation of metabolic waste products in the microenvironment lead to a metabolic switch that impairs optimal proliferation and function of T cells. Recent evidence suggest that immune checkpoint inhibitors might regulate the metabolic landscape in the tumor microenvironment. CTLA-4 and PD-1 binding to their respective ligands impairs the metabolic phenotype of T cells by inhibiting glycolysis, thus causing reduced cytokine secretion and an exhausted effector T cell phenotype. Interestingly, these inhibitors have the opposite effect on the metabolic program of cancer cells, for example, the ligation of PD-L1 upregulates glycolysis in cancer cells by promoting glucose uptake and production of lactate that leads to tumor growth and metastasis.

- Among the therapeutic strategies that have been proposed to shift this imbalance are the combination of the inhibitors with rapamycin or metformin to enhance the cytotoxic and memory T cell function, however those findings wait for further validation in randomized studies.

- While the field of immunotherapy has advanced significantly in the past decades, much knowledge is needed to achieve a future where the benefit of these therapies could be easily provided to more patients, but some really important questions arise, for example, how to select patients who are most likely to respond to immune checkpoints inhibitors, how to combine this therapy with other treatments modalities to reduce toxicity and resistance, and how to use these therapies in newly defined standards of care and when to stop treatment. the answers to these questions will help define a promising vision for the future of cancer treatment.

Quiz

Now test your knowledge with these questions!

Download these Resources:

References

- Chen D, Mellman I. Oncology Meets Immunology: The Cancer-Immunity Cycle. Immunity 2013, 39: 1-10.

- Kaufman H, et al. The promise of Immuno-oncology: implications for defining the value of cancer treatment. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer 2019, 7:129.

- Esfahani K, et al. A review of cancer immunotherapy: from the past, to the present, to the future. Curr Oncol. 2020, 27 (S2):87-97.

References

- Chen D, Mellman I. Oncology Meets Immunology: The Cancer-Immunity Cycle. Immunity 2013, 39: 1-10.

- Kaufman H, et al. The promise of Immuno-oncology: implications for defining the value of cancer treatment. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer 2019, 7:129.

- Esfahani K, et al. A review of cancer immunotherapy: from the past, to the present, to the future. Curr Oncol. 2020, 27 (S2):87-97.