Introduction

- Since the birth of modern biotechnology, hundreds of biotherapeutics have been developed and approved by the US-FDA for human use.

- Albeit historically drug target classes have been mostly receptors, enzymes, ion channels and transporters, with the development of antibody-based therapies and the advances in the knowledge of the molecular basis of pathologies, soluble protein ligands (i.e. inflammatory cytokines) have become one of the most important classes of drug targets in the last decades.

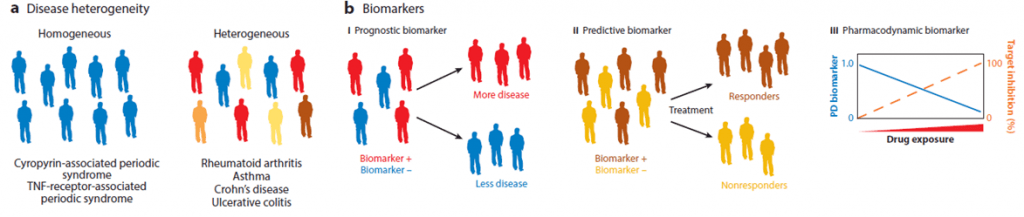

- As most autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, as well as cancer, are defined by a common set of symptoms and diagnostic criteria but arise from a spectrum of molecular causes, treatments with single therapies only benefit a small subset of patients.

- Therefore intra-disease heterogeneity suggests that newer therapies as multitarget drugs may be required to maximize benefit. Furthermore, fusion proteins or aptamers have also become attractive to achieve the therapeutic goal (blocking ligand-receptor interaction), and many others are currently in study.

Cytokines as Targeted Ligands

- Cytokines constitute 50% of the ligands targeted by FDA-approved drugs (total n=22).

- The first one to be approved and the one that is also most targeted is TNF, with 5 approved drugs. This is probably due to the central role it has in the proinflammatory cytokine cascade, becoming a key target for inflammatory disease treatment such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA, more info below), Crohn´s disease and others under study.

- VEGFA, a key regulator of angiogenesis, is another heavily targeted ligand, with 5 approved drugs and another 18 in preclinical and clinical studies. Because of its role in tumor angiogenesis, VEGFA is a relevant target for the treatment of multiple cancers, alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

- More recently VEGFA has also become an attractive target for eye disorders characterized by ocular neoangiogenesis, as age-related macular degeneration.

Classification of Ligand Targeting Drugs

- Currently, the predominant class (approximately three-quarters of the approved ligand targeting drugs) is full-length monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), due to their success based on specificity, stability and adaptability.

- Nevertheless, this therapeutic approach has presented setbacks that compromise drug efficacy and safety, mostly associated with immunogenicity (presence/generation of anti-drug antibodies).

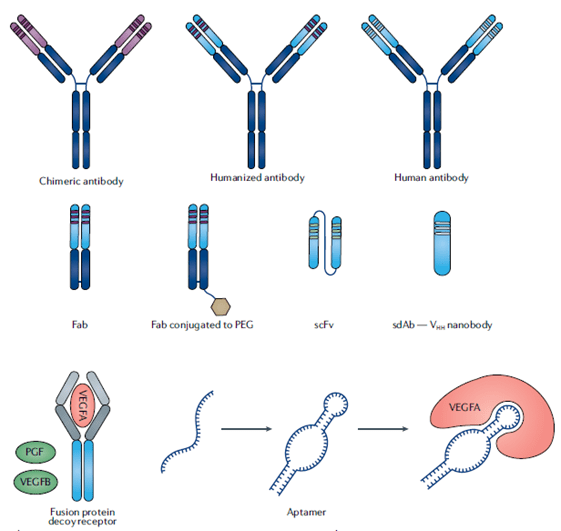

- This has been solved by the creation of technologies that reduce the amount of foreign derived sequences (see Figure 1):

- Chimeric monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

- Humanized mAbs

- Human mAbs

- The choice of IgG subtype is not trivial, since depending on the therapeutic application one or other antibodies may be more suitable. As an example, IgG2 and IgG4 have lower potential to elicit effector functions, so this feature may be advantageous for applications that are intended to dampen immune responses.

- Another relevant class of ligand targeting drugs are decoy receptors, which incorporate the binding domains from endogenous ligand receptors to trap the ligand.

- The large size of these molecules (approx. 150 kDa) has the advantage of extended-half life, but this very same feature is detrimental to tissue penetration.

- Antibody fragments and single-domain antibodies (nanobodies) are strategies that have solved the above stated issues associated with large size molecules, but have the disadvantage that require frequent dosage because of the rapid clearance. If required (mostly necessary for chronic therapies), this can be solved by modifications as PEGylation.

- Aptamers are small easy-to-produce nucleic acid polymers that fold into distinct 3D structures to bind specifically and with high affinity to a defined target with no immunogenicity issues, which has converted them into compelling strategies, with the first approval in 2004.

- Concerns related to the instability due to nuclease degradation have been solved by the development of spiegelmers, mirror-image configuration of aptamers that are not composed of natural L-nucleotides and therefore, are resistant to nucleases degradation. These latter are currently in phase II trials.

- Other approaches such as gene therapies (delivering a copy of the defective gene to the cell through vectors) or oligonucleotide therapies (affecting the production of the ligand before it reaches the protein stage) –e.g. antisense oligonucleotides or small interfering RNAs- have not gained approval for cytokine related applications, but are under investigation for their potential.

Targeting Soluble Ligands vs Receptors

- Soluble ligands are easier to reach than their receptors in some scenarios, e.g. inaccessible solid tumors.

- In some cases targeting receptors can affect various pathways –because of the pleiotropy of the cytokines-, while engaging with ligands may be a more beneficial approach, e.g. clinical trials with an IL-17A targeting mAb showed improvement in patients with RA, whereas trials targeting IL17R –that inhibits all members of the IL-17 family- showed no beneficial response.

- Nevertheless, in organ transplants, a mAb against IL-2R has shown to suppress rejection, supporting the notion that each condition has to be thoroughly studied in order to decide the best course of action.

- Because of the dual effect of IL-2 in the induction of immune responses by stimulating T cells and the maintenance of the Treg subset that could dampen immune responses, particular attention has to be put into the approaches regarding its control. That has led to the generation of mAb to IL-2 that can preferentially stimulate the expansion of one or other subsets, depending on the interacting part of the cytokine.

TNF as a Model Soluble Target in Rheumatoid Arthritis

- RA is a joint-destructive chronic inflammatory disease, in which cytokines play a central role. Therefore, they represent an attractive therapeutical target.

- Of them, TNF has been the most studied and is a well-established target in advanced disease. Nevertheless others as IL6, IL1, IL17 and GM-CSF are in different stages of approval (some in market, some under investigation), and are intended for use in early stages or in non-responders.

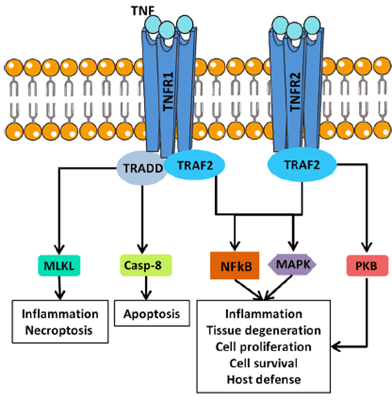

- TNF is a pleiotropic cytokine that exerts both homeostatic and pathological functions, its versatility being related to the existence of two different receptors. It is suggested that TNFR1 is mainly associated with inflammation and tissue degradation while TNFR2 primarily mediates local homeostatic effects (see Figure 2).

- In cultures of synovial cells from RA patients, the blockade of TNF significantly decreases the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis, as IL-6, IL-1 and GM-CSF. That linear model on hierarchy, where TNF drives the downstream cytokines, would explain the dominance of anti-TNF treatments, and also suggests that better therapeutics can be achieved by combining cytokine blockade.

- Currently, five different biologicals have been approved for the treatment of RA (mAbs, Fc fusion protein and and pegilated Fab fragment). Nevertheless, the vast majority of patients are non-responders and/or exhibit adverse effects, pointing out to the need of new therapies (directed to different targets or bispecific molecules, see below) or combinatory treatments. The major reason for failure can be attributed to disease heterogeneity.

- Another point of interest would be the definition of reliable biomarkers of response that would allow the stratification of patients, leading to a more personalized treatment (see Figure 3). This can at least mitigate the issues of patient heterogeneity. For example, several SNP in the promoter region of TNF have been related to clinical responses, allowing to use certain therapies only in certain patients.

Targeting Multiple Ligands

- 16% of US-FDA approved drugs that target soluble ligands bind multiple ligands. These comprise bispecific or multi-specific agents designed to bind unrelated ligands or that are naturally able to bind different epitopes on related proteins.

- This is particularly interesting in complex diseases as cancer where therapeutic resistance emergence may lead to resistance and reduction of treatment efficacy. It is also a matter of interest in view of disease heterogeneity displayed in several inflammatory syndromes.

- Another benefit is the reduction on costs for using a single agent instead of two or more.

Quiz

Now test your knowledge with these questions!

Download these Resources:

References

- Attwood, M., et al “Soluble ligands as drug targets” Nat. Rev. 2020

- Abbas, A., et al “Revisiting IL-2: Biology and therapeutic prospects” Sci. Immunol. 2018

- Noack, M. et al “Selected cytokine pathways in rheumatoid arthritis” Semin. Immunopathol. 2017

- Ghilardi, N. et al “30 years of biotherapeutics development- What have we learned?” Annu. Rev. Immunol 2020.

References

- Attwood, M., et al “Soluble ligands as drug targets” Nat. Rev. 2020

- Abbas, A., et al “Revisiting IL-2: Biology and therapeutic prospects” Sci. Immunol. 2018

- Noack, M. et al “Selected cytokine pathways in rheumatoid arthritis” Semin. Immunopathol. 2017

- Ghilardi, N. et al “30 years of biotherapeutics development- What have we learned?” Annu. Rev. Immunol 2020.