Introduction

- The field of immunology has a good understanding of the role of the immune system in the physiology of the body and pathophysiology of hundreds of diseases, making it easier to focus resources on the development of immunotherapies for different conditions that have affected humankind for a very long time.

- Immunotherapies stimulate, modify, or suppress our immune system in different ways to treat different illnesses like cancer and chronic inflammatory diseases. These types of therapies are becoming more efficient and will soon become the primary option for treatment thanks to their effectiveness and are often the last biological intervention for some patients.

History

- The manipulation of the immune system to treat cancer began more than 100 years ago when Dr. William B. Coley, a New York surgeon, lost his first patient with sarcoma. This got Coley interested in researching this condition and reviewing the medical records of the hospital..1

- Coley found one case of a seven-year-old boy with an inoperable neck sarcoma that started to regress and got “cured” when the boy had a bacterial infection in the upper layer of the skin (erysipelas).

- That made Dr Coley attempt to initiate erysipelas in cancer patients as potential treatment strategy.1

- In 1892 Coley tried to use a heat-killed Streptococcus but this had little effect; he then came up with the idea of improving the virulence of the bacteria and decided to add Serratia marcescens into the formula leading to major results. Later, this vaccine received the name of “Coley´s toxins”. 1

- The type of cancer that had a better outcome to Coley´s toxins was sarcoma followed by lymphoma.

- Other types of cancer like testicular, breast or melanoma did not have a good response and the majority of those who got treated with Coley´s toxins relapsed in less than five years.1

- After coley´s death, radiotherapy and conventional chemotherapy began to replace the Coley´s toxins. However, this development inspired many investigations into the role of immunology in cancer and helped to develop new types of immunotherapies.

- In the timeline of immunotherapies more than 30 years after Coley´s toxins, the use of some cytokines like TNF, interleukin-2 and IFN α in local or systemic treatment came as a next generation of immunotherapy.

- In 1997 the first monoclonal antibody, anti-CD20 Rituximab, was approved to use in B cell malignancy.

- In 2011, the FDA approved Ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of metastatic melanoma, making this the first checkpoint inhibitor launched.

- In 2012 another novel type of immunotherapy was developed, when for first time CAR T cell therapy cured a seven years old girl from acute lymphocytic leukemia.

- Another important part of the history of immunotherapy took place in 2018 when James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation.

- The two molecules that gave them the prize were Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) discovered by James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo, respectively.

- They found that these molecules are negative regulators of T cell activation and are important targets for cancer treatment.

The physiology behind the immunotherapy

- Cancer Immunology is complicated, with contributions from genetics and microenvironment; regulatory proteins can have either positive or negative effects on the immuno-pathological response.

- The normal immune response is composed of multiple important steps that can be corrupted by cancer such as the dysregulation of cellular division, which becomes a target for new immunotherapies.

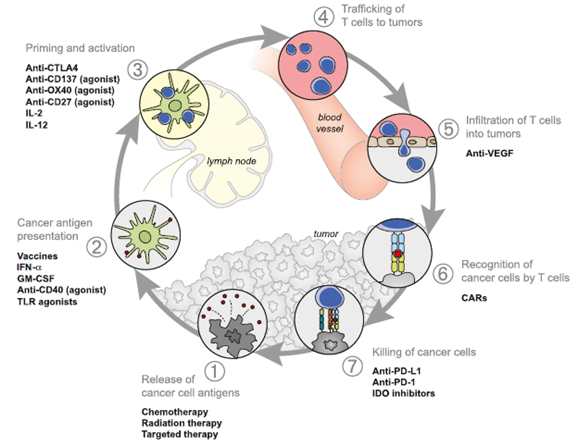

- Immunotherapy must maintain a fine balance between boosting and decreasing the immune response. Experience has shown that an unfavourable balance could lead to negative results or to the amplification of autoimmune responses. The most used cancer immunotherapeutics target one of the following processes associated with cancer development and/or persistence (Figure 1):

-

- The first important event is the capture and processing of cancer neoantigens by dendritic cells.2 Chemotherapy and radiotherapy can target this activity by either directly killing tumor cells or increase the processing of neoantigens leading to the destruction of tumor cells.2

- The second event is the presentation of cancer neoantigens to T cells. This step can be targeted using a cancer vaccine, however thus far researchers have experienced difficulties such as the selection of tumors antigens to include in the vaccine, and the mode of vaccine delivery that can lead to a robust response.2 For more detail read the following section dedicated to Cancer Vaccines.

- Priming and activation of T cell response can be targeted by enhancing the response of T effector cells and preventing a T regulatory cell response to the tumor. An example of this type of immunotherapy is the use of antibodies targeted to CTLA -4, a potent inhibitory protein that binds strongly to CD80 and CD86.2,3 Cancer cells use different proteins to block cytotoxicity. One of the most important is PD-1, a potent inhibitory target of immunotherapy. Thus another form of immunotherapy consists in blocking PD-1 with antibodies, avoiding the suppression of anti-tumor T cells and restoring the activity of T cells suppressed by the PD-1 pathway.2 Read the following section on Check-Points Blockade Based Therapies for more detail.

For T cells to provide anti-tumor activity they need to traffic and infiltrate the tumor microenvironment (TME). T cells that perform such functions are known as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS) and have been considered another target for immunotherapy.2 For more detail read the following section dedicated to TILS. - Trafficking to the TME is not sufficient; for TILs to perform their function they need to recognise cancer cells. Another type of immunotherapy targets T cell recognition by genetically modifying T cells to express chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) specific for antigens in the tumor.2 For more detail read the following section dedicated to CAR therapies.

Conclusion

- Thanks to developments in the field of immunology, immunotherapy has provided new means to explore the treatment of cancer.

- Not all types of cancer are susceptible to immunotherapy. This has led to the use of combination immunotherapy such as anti-CTLA 4 plus anti-PD-1, or CART cell plus anti-PD-1,with some success. Investigations are also ongoing to find new types of immunotherapies.

Quiz

Now test your knowledge with these questions!

Download these Resources:

References

- CO. S. Coley’s toxins in perspective. Nature. 1992;357(6373):

- Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10.

- Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 1996 Mar 22 [cited 2020 Nov 12];271(5256):1734–6. Available from: https://mdanderson.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/enhancement-of-antitumor-immunity-by-ctla-4-blockade

References

- CO. S. Coley’s toxins in perspective. Nature. 1992;357(6373):

- Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10.

- Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 1996 Mar 22 [cited 2020 Nov 12];271(5256):1734–6. Available from: https://mdanderson.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/enhancement-of-antitumor-immunity-by-ctla-4-blockade