Type 2 and regulatory immune responses in helminth infections

- Over one third of the human population is affected by one or multiple helminth parasites.

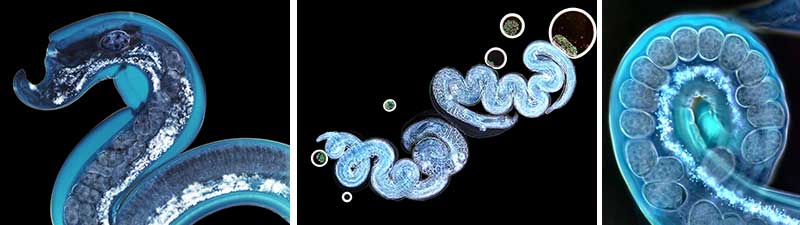

- Helminth parasites are complex multicellular, eukaryotic pathogens with different life stages, which can affect a variety of different human tissues.

- Helminths induce an entirely distinct immune response compared to other microbial pathogens. The immune response is characterised by a ‘Type 2 immunity’, but is in addition modified by strong regulatory responses.

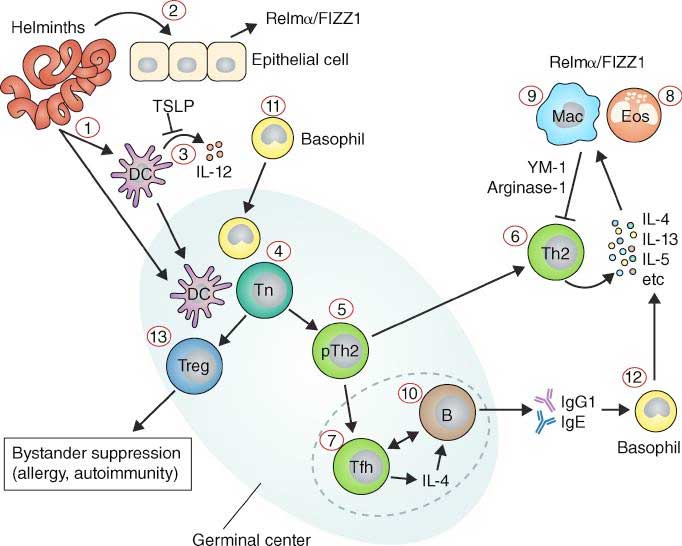

- The immune response is comprised by following main components:

- Cellular: Eosinophils, basophils, alternatively active macrophages (AAM), Innate lymphoid type 2 cells (ILC2), T helper type 2 cells (TH2 cells), regulatory T cells

- Cytokines: Interleukin (IL-)4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13, IL-25, IL-33, TSLP, TGF-beta

- Antibodies: IgG1, IgG4, IgE

- The detailed immune response is complex and varies between different helminth parasites. A general overview is provided in Figure 1.

- Treatment with anti-helminthic drugs can boost immune response, but does not necessarily induce protection from re-infection.

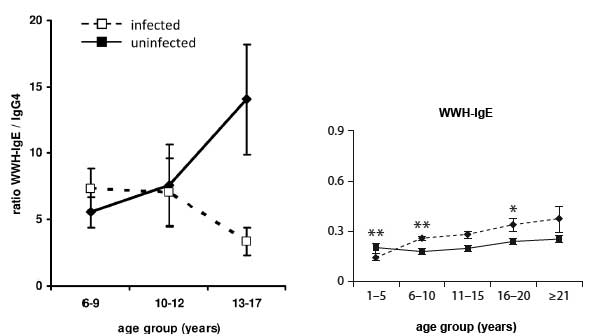

- Sterile immunity, protection from re-infection may develop slowly over time following cumulative exposure to helminth parasites and/or with multiple rounds of treatment. Protection is associated with IgE.

Immune responses in natural human infection

- The immune response in helminth infection is complex and depends on several factors including i) transmission dynamics, ii) intra-population exposure, iii) previous therapeutic intervention and iv) pattern of co-infections. These complex interactions cannot be easily mimicked in experimental animal models of helminth infection.

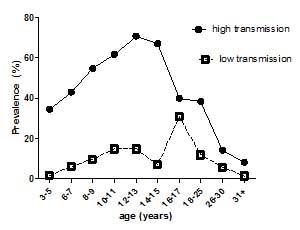

- Immune responses vary with age, gender, treatment and exposure and are reflected at population (Figure 2) and individual levels. These differences are reflected in patterns of immune responses. Levels of antibodies, cytokines, but also cellular responses vary with age and intensity of transmission (Figure 3).

- Infection patterns vary between different helminth parasites. Most helminth parasites show a peak in infection prevalence and infection levels at a certain age group. In schistosomiasis (S. mansoni and S. haematobium), infection usually peaks in age groups under 20, while sometimes it peaks in older people. Infections can also remain at high levels.

- These differences in age-infection patterns not only reflect different exposures, but also differences in the development of immunity.

Group 2 Innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) in the immune response against helminth parasites

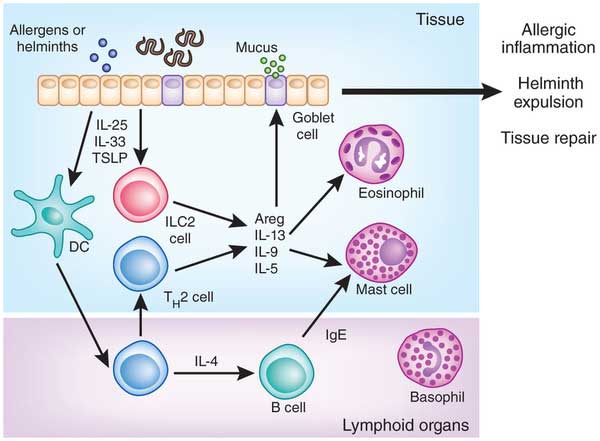

- Innate lymphoid cells (ILC) are recently described cells that have transformed our understanding of the role of innate immune responses in the generation of adaptive immune responses. Currently three different subsets are known: ILC1 resembling TH1 cell, ILC2 resembling TH2 cells and ILC3 resembling TH17 and TH22 cells.

- ILCs are lymphocytes, but do not belong to classical subsets such as CD3 T cell, NK cells or B cells. Group 2 Innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) were originally described in experimental models of helminth infections and initially called nuocytes. Markers of human ILC2s are CD127 (IL-7Ra), CRTH2, CD161 and the transcription factor GATA3.

- ILC2s produce the classical TH2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 and have been shown to be crucial for protective immune responses in experimental helminth infection and recently shown to be modulated in human helminth infection.

- Figure 4 shows a schematic overview of the role of ILC2 in inducing type 2 immune responses in helminth infection. Helminths disrupt the epithelial barrier, which leads to a release of IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP. These epithelial cytokines activate ILC2 which in turn release IL-5, IL-13 and IL-9 cytokines, which cause the recruitment of eosinophils and mast cells. They provide an early type-2 reaction, which later on is amplified by classical TH2 cells.

- In addition ILC2 are important in tissue homeostasis and repair, but also play a role in allergic sensitization.

Helminth infections and the control of allergy and autoimmune disorders

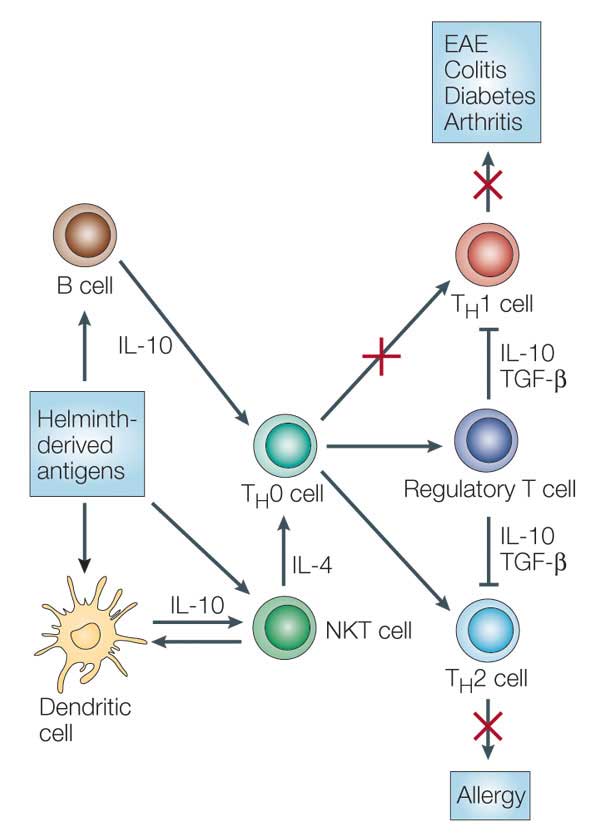

- Helminths are known to drive a regulatory immune response by inducing regulatory T cells and IL-10. Induction of such a regulatory immune response leads to suppression of the host immune response against the parasite including reduced T cell proliferation, down-regulation of proinflammatory TH1 responses and modulation of TH2 responses (Figure 5).

- The immune suppression caused by helminths can by either attributed to active manipulation by the parasite (i.e. by releasing immunes-suppressive compounds) or to a reaction by the host immune system to limit immune mediated damage.

- The suppressed immune response by regulatory T cells and IL-10 is not restricted to parasite-specific antigens and can also affect immunity against other pathogens (bystander effect).

- This bystander suppression may be a disadvantage for the immune response against concomitant infection such as tuberculosis or for efficacy of vaccination. On the other hand, this immune modulation might be beneficial for preventing allergy and autoimmune disease.

- Multiple studies indicate a reverse relationship between helminth infection and allergic responses, but the scale of the effects depends on the helminth pathogen, and duration and intensity of infection. Modulation of allergic responses is more likely to happen at the level of sensitization.

- In autoimmune diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes. Helminth products are being considered as therapeutic modalities, although evidence from clinical trials is lacking.

Schistosomiasis – General Information and Latest Numbers

- According to the latest WHO report Schistosomiasis is a disease of the poor leading to chronic diseases and is responsible for 200,000 deaths annually (WHO 2015).

- The WHO states that the burden of Schistosomiasis is generally underestimated. As a prevention method WHO aims on treating all school aged children annually to interrupt the infection cycle. In 2017 around 99 million people and almost 75% of all school children in endemic areas received treatment.

- Besides mass drug administration the immunity of reinfection is subject to broad research.

- There is data supporting the evidence of IgE in acquired protective immunity. Specifically, empirical data shows that the IgE responses to the tegument allergen-like (TAL) protein family, adds to the, yet not fully understood, role in the protection against reinfection immunity (Oettle and Wilson 2017), therefore further studies are necessary.

Immunological Implications of Schistosomiasis

- Schistosomiasis is transmitted through cercariae, which are the larval form of blood flukes, through contact in infested sweet water. The human habitat for blood flukes are veins and the intestines.

- The critical part of Schistosomiasis is the egg production and the consecutive immunological reactions triggered by various cytokines, with different detectable levels e.g. low levels of type 2 cytokines and high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines especially in school aged children, this combination is a possible detection pattern of an active infection. (Costain, MacDonald et al. 2018)

- The reproductive cycle of schistosomes rely in many ways on the adaptive and innate immune system and its signals e.g. maturation egg movements. Worm growth and reproduction is fundamentally inhibited in the absence of CD4+ T cells. (Costain, MacDonald et al. 2018)

- To complete the reproductive cycle schistosomes also appear to induce angiogenesis via pro-angiogenetic factors such as VEGF.

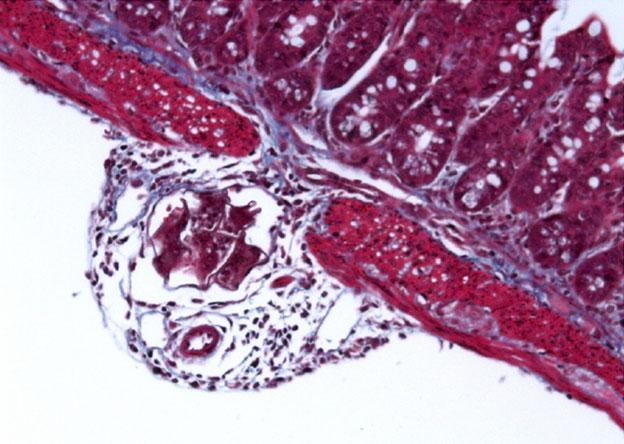

- After entering the vessels the eggs have to pass the barrier of the intestinal wall. This is achieved without a provoked inflammation, though not yet not fully understood studies suggest that egg derived proteases remodel the intestinal vasculature a process that helps the eggs pass the multi-layer barrier. (Turner, Narang et al. 2012)

- Within the hosts tissue schistosoma eggs produce a broad assortment of toxic and immune modulating substances. The eggs act as a nucleus for granuloma formations with many immune cells involved e.g. Th2 CD4 T cells, macrophages, eosinophils and mast cells resulting in the secretion of a spectrum of cytokines e.g. IL-4, IL-13 and IL-5. (Hams, Aviello et al. 2013)

- The levels of these cytokines are also influenced by common co-infections e.g. plasmodium sp. Studies showed significantly reduced levels of IL-2, concomitant with the infection with plasmodium and schistosomas. (Lyke, Dabo et al. 2012)

- Yet another co-infective immunological modulation is the suppression of basophil histamine release and other IgE dependent reactions with coinfection of schistosomas and ankylostoma (hookworms). (Pinot de Moira, Fitzsimmons et al. 2014)

Quiz

Download the Presentations for this section:

Download these Resources:

The Interdependence between Schistosome Transmission and Protective Immunity

1 file(s) 355.17 KB

Drug Resistance and Species-Specific Drug Action in Schistosome Parasites

1 file(s) 616.54 KB

Related Talks

William Hornsell, University of Cape Town – Helminth Infections

Sergey Yegorov, University of Toronto – Helminths

References

- Costain, A. H., et al. (2018). “Schistosome egg migration: mechanisms, pathogenesis and host immune responses.” Frontiers in immunology 9.

- Hams, E., et al. (2013). “The schistosoma granuloma: friend or foe?” Frontiers in immunology 4: 89.

- Lyke, K. E., et al. (2012). “Reduced T regulatory cell response during acute Plasmodium falciparum infection in Malian children co-infected with Schistosoma haematobium.” PLoS One 7(2): e31647.

- Oettle, R. C. and S. Wilson (2017). “The interdependence between schistosome transmission and protective immunity.” Tropical medicine and infectious disease 2(3): 42.

- Pinot de Moira, A., et al. (2014). “Suppression of basophil histamine release and other IgE-dependent responses in childhood Schistosoma mansoni/hookworm coinfection.” The Journal of infectious diseases 210(8): 1198-1206.

- Turner, J. D., et al. (2012). “Blood flukes exploit Peyer’s patch lymphoid tissue to facilitate transmission from the mammalian host.” PLoS pathogens 8(12): e1003063.

- WHO (2015). “WHO Schistosomiasis Report.” Retrieved 23.11.2019, 2019, from https://www.who.int/schistosomiasis/en/.

References

- Costain, A. H., et al. (2018). “Schistosome egg migration: mechanisms, pathogenesis and host immune responses.” Frontiers in immunology 9.

- Hams, E., et al. (2013). “The schistosoma granuloma: friend or foe?” Frontiers in immunology 4: 89.

- Lyke, K. E., et al. (2012). “Reduced T regulatory cell response during acute Plasmodium falciparum infection in Malian children co-infected with Schistosoma haematobium.” PLoS One 7(2): e31647.

- Oettle, R. C. and S. Wilson (2017). “The interdependence between schistosome transmission and protective immunity.” Tropical medicine and infectious disease 2(3): 42.

- Pinot de Moira, A., et al. (2014). “Suppression of basophil histamine release and other IgE-dependent responses in childhood Schistosoma mansoni/hookworm coinfection.” The Journal of infectious diseases 210(8): 1198-1206.

- Turner, J. D., et al. (2012). “Blood flukes exploit Peyer’s patch lymphoid tissue to facilitate transmission from the mammalian host.” PLoS pathogens 8(12): e1003063.

- WHO (2015). “WHO Schistosomiasis Report.” Retrieved 23.11.2019, 2019, from https://www.who.int/schistosomiasis/en/.