Immune Response to HIV Vaccine Candidates

- The most efficacious HIV vaccine candidate to date was the RV144 vaccine run in a trial in Thailand – with 31.5% efficacy.

- Although the trial showed very modest efficacy, and was based on small numbers, it provided important knowledge towards making a more effective vaccine.

- Based on the results, a similar trial is being conducted in Southern Africa.

- The RV144 vaccine consisted of a canarypox prime with a recombinant gp120 boost.

- Immunology studies of the potential mechanism of the vaccine strategy revealed that CD8+ T-cell responses did not play a role.

- The CD4+ T-cell response, although modest, was targeted against peptides derived from the V2 loop of the HIV-1 envelope.

- It was found that non-neutralising IgG antibody responses targeting the V1/V2 loop of the HIV-1 envelope was the major correlate of risk.

- The binding of IgA antibodies to the V1/V2 loop positively correlated with HIV infection and it is considered that IgA competes with IgG

- Whether IgG to the V1/V2 region is a correlate of protection needs to be shown in further vaccine trials.

- Development of a vaccine which elicits higher levels of V1/V2-specific IgG antibodies and lower levels of envelope-specific IgA antibodies may improve the efficacy of future HIV-1 vaccines.

- This finding was surprising as primate models have previously shown non-neutralising antibodies to be ineffective in preventing SHIV transmission.

- The results of this study reveal new possibilities for non-neutralising antibodies playing an important role in the immune response to prevent HIV transmission by the process of antibody-dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

- Earlier efficacy trials, the STEP and Phambili trials, commenced in 2004 and used a trivalent adenoviral vector vaccine which encoded for HIV-1 gag, pol and nef and aimed to induce high titres T-cell responses.

- Although this vaccine candidate had previously been found to control SHIV infections in non-human primates, the vaccine not only had low efficacy in humans but also increased the risk of acquiring HIV-1 in vaccinated volunteers who had pre-existing antibodies to adenovirus and/or volunteers who were uncircumcised.

- The increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition was thought to be caused by the presence of adenovirus-specific CD4+ lymphocytes in the mucosa but this hypothesis has been dismissed by subsequent studies.

- There is still debate in the HIV-1 vaccine field about whether general immune activation in the mucosa increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition although studies in vitro have found that it does.

Germinal Centres and T follicular helper responses in HIV antibody-based vaccines

- Germinal centres are regions in lymph nodes or the spleen where B cell activation, proliferation, somatic hypermutation, selection and differentiation into plasma and memory cells occur and this makes them important in antibody-based vaccine research. Find out more – B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- B cell activation which occurs in germinal centres is initiated in follicles after the cells have encountered specific antigens. The B cells then move to the periphery of those follicles and the antigen-specific B cells can interact with antigen-specific T cells.

- T follicular helper (Tfh) cells are central in germinal centre activity. They interact with B cells in germinal centres to provide adequate help in the developmental steps taken by B cells in these areas. Tfh cells also control the number of B cell divisions and therefore control how much somatic hypermutation occurs.

- Tfh cells express surface markers including PD-1 and/or ICOS, as well as CXCR5. Tfh differentiation, like B cells, is controlled by Bcl-6 and in this way Bcl-6 regulates GC responses.

Tfh and Germinal centres in HIV vaccines

- Broadly neutralising antibodies are the goal for a vaccine response towards HIV.

- These antibodies have usually undergone multiple rounds of somatic hypermutation. The process of somatic hypermutation occurs in germinal centres.

- Therefore monitoring germinal centre activity may be important in evaluating vaccine-dependent antibody responses.

Immune Response to Malaria Vaccine Candidates

Malaria vaccine targeting the sporozoites and Pre-Erythrocytic Stages of Infection

- Human vaccine trials demonstrated that sterile immunity induced by exposure to radiation-attenuated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites was not strain specific and could last for at least 10 months.

- From these seminal studies, two main streams of research developed. One of them has focused on the development of subunit vaccines consisting of well-defined parasite antigens. The second line of research proposes the development of a vaccine based on the use of whole attenuated sporozoites.

- RTS,S (also known as Mosquirix™) is an advanced malaria vaccine and confers significant protection against Plasmodium falciparum infection in humans.

- The RTS,S vaccine was engineered using genes from the pre-erythrocytic circumsporozoite protein (CSP) of the Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasite and a viral envelope protein of the hepatitis B virus (HBsAg), to which was added a chemical adjuvant (AS01) to increase the immune system response. Infection is prevented by inducing humoral and cellular immunity, with high antibody titers, that block the parasite from infecting the liver.

- Phase III clinical trials in over 15,000 African children demonstrated that the vaccine efficacy of RTS,S ranges from 25–55%, depending on the age of the children and the intensity of transmission, and that this protection appears to be mediated by antibodies and perhaps also CD4+ T cells.

- The partial efficacy of the RTS,S vaccine waned over time with a significant reduction by 3 years post-immunization.

- The limited efficacy RTS,S may be due to the narrow breadth of the immune responses induced by RTS,S, which consisted mostly of antibodies against the repeat domain of the CSP, which are known to neutralize sporozoite infectivity.

- While this vaccine also induces some antibody and CD4+ T cell responses against the C-terminal region of the CSP, the anti-parasite effect of these immune mechanisms has not been demonstrated.

- Another significant limitation of the RTS,S vaccine is the fact that it does not induce CD8+ T cell responses, which represent an efficient anti-parasite mechanism that eliminates malaria liver stages in rodent model systems.

- Development of vaccines capable of inducing CD8+ T cell responses in addition to antibodies may require major changes in the design of the vaccine construct and will also necessitate the identification of a number of CD8+ T cell epitopes presented by class I MHC molecules in hepatocytes expressed in most if not all individuals living in malaria endemic areas.

- Vaccination with whole sporozoites, attenuated by irradiation or genetic manipulation, has recently acquired a new impetus.

- This new approach is based on the use of cryopreserved parasites instead of exposure of individuals to the bites of infected mosquitos as was done in the original studies.

- Limited clinical trials with volunteers from non-endemic areas demonstrated the development of sterilising immunity in all immunized volunteers after 5 immunizations with irradiated sporozoites administered intravenously.

- It was shown that immunized individuals developed strong antibody responses to sporozoites as well as T cell responses.

- Recent trials in adults in malaria endemic areas also showed induction of sterile immunity, but only in 20–30 percent of vaccinees.

- Another variation of the whole sporozoite immunization platform is sporozoite infection under the cover of chloroquine treatment, which allows infection of the liver but prevents progression of blood-stage parasites to the point of clinical illness.

- Naïve volunteers immunized by this chemoprophylaxis and sporozoite immunization (CPS) strategy involving very few mosquitoes develop efficient sterile immunity against subsequent challenge infection by mosquitoes carrying homologous parasites.

- In contrast, when the immunized volunteers were challenged with blood-stage parasites, they were not protected, suggesting that immunity was directed to preerythrocytic stages.

Malaria vaccine targeting the asexual Blood Stages of Infection

- The progressive development of naturally acquired immunity to the erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum malaria with age has been recognized for many years.

- The contributions of antibodies to this immunity are due in part to a groundbreaking study showing that passive transfer of IgG from adult Africans long exposed to malaria could drive down erythrocytic malaria parasite levels in children with this disease.

- Many blood-stage vaccine candidates have been identified based on studies of mouse malaria parasites, and in some cases protective immunity to these proteins has also been demonstrated in non-human primates.

- In general these antigens are involved in merozoite invasion of red cells, and experience with model systems has shown that high concentrations of specific antibodies are necessary for protection in vivo; the levels required (perhaps 80–100ug/ml) challenge human vaccinology in terms of platforms which could generate and maintain such levels.

- Some data has suggested that naturally acquired immunity to malaria is primarily dependent on immune responses to parasite-encoded antigens found on the surface of the infected red cell rather than on the merozoite.

- Antibodies to these antigens accumulate over time with progressive exposure to various parasite strains.

- These large proteins (approximately 300kDa) with multiple variable domains and ability to switch expression from one to another have been a great challenge for vaccine developers.

Malaria vaccine targeting the sexual and Mosquito Stages of Malaria

- New insights into the biology of sexual stage parasites and to the insect vector will be necessary to decrease transmission, perhaps including a transmission blocking vaccine (TBV).

- Since the female Anopheline mosquito picks up human plasma at the same time as she feeds on blood containing gametocytes, antibodies from the vertebrate blood are also transferred to the mosquito midgut and can function there to block transmission.

- This strategy derives from original observations on avian models of malaria which led to experiments showing that chickens immunized with inactivated P. gallinaceum gametocytes produced a transmission blocking activity in the serum that inhibited parasite development in the mosquito.

- Since the vaccine recipient does not directly and immediately benefit, this approach was originally considered to be an “altruistic vaccine”.

Immune Response to TB Vaccine Candidates

- Currently, Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is the only vaccine approved for use to prevent TB.

- BCG vaccination is highly effective at preventing TB-meningitis and extra-pulmonary disseminated TB; however, its efficacy against pulmonary TB (PTB) in different human populations (children, youth, adult, and elderly) varies.

- Some studies have shown 80% efficacy, whereas others have shown none.

- BCG induces a potent CD8 T-cell response, with cytokine-producing or cytotoxic potential, in infants.

- An induction of FoxP3 mRNA expression in some mycobacteria-stimulated whole-blood samples has also been found, which suggests the presence of BCG-induced regulatory CD4 T cells.

- Stimulation of whole blood with mycobacterial antigens has resulted in a consistent pattern of cytokine release: significant numbers of infants make either large amounts of the effector cytokine interferon-gamma, or large amounts of the regulatory cytokine interleukin-10, but not both.

- Further research will determine whether CD8 or regulatory CD4 T-cell responses, as well as “outlier” cytokine responses, are associated with vaccination-induced protection against tuberculosis.

- The poor efficacy conveyed by BCG at preventing TB has been attributed to many factors, including human and mycobacterial genetics, exposure to environmental mycobacteria (EM), coinfections with viruses and/or parasites, geographical location, and importantly, socioeconomic and nutritional factors.

- However, the fundamental question remains as to why BCG fails to confer sterilizing immunity to TB.

- BCG is primarily believed to mediate immunity through the development of antigen (Ag)-specific memory T cells, which act quickly following a subsequent infection with M.tb.

- This is the fundamental reason why BCG works against disseminated TB and TB meningitis. However, why the same mechanism fails to prevent PTB remains poorly understood.

- Developing a successful vaccine against M.tb infection requires an understanding of how immunity develops following BCG vaccination, and the roadblocks behind why protective immunity is not sustained.

How does BCG work?

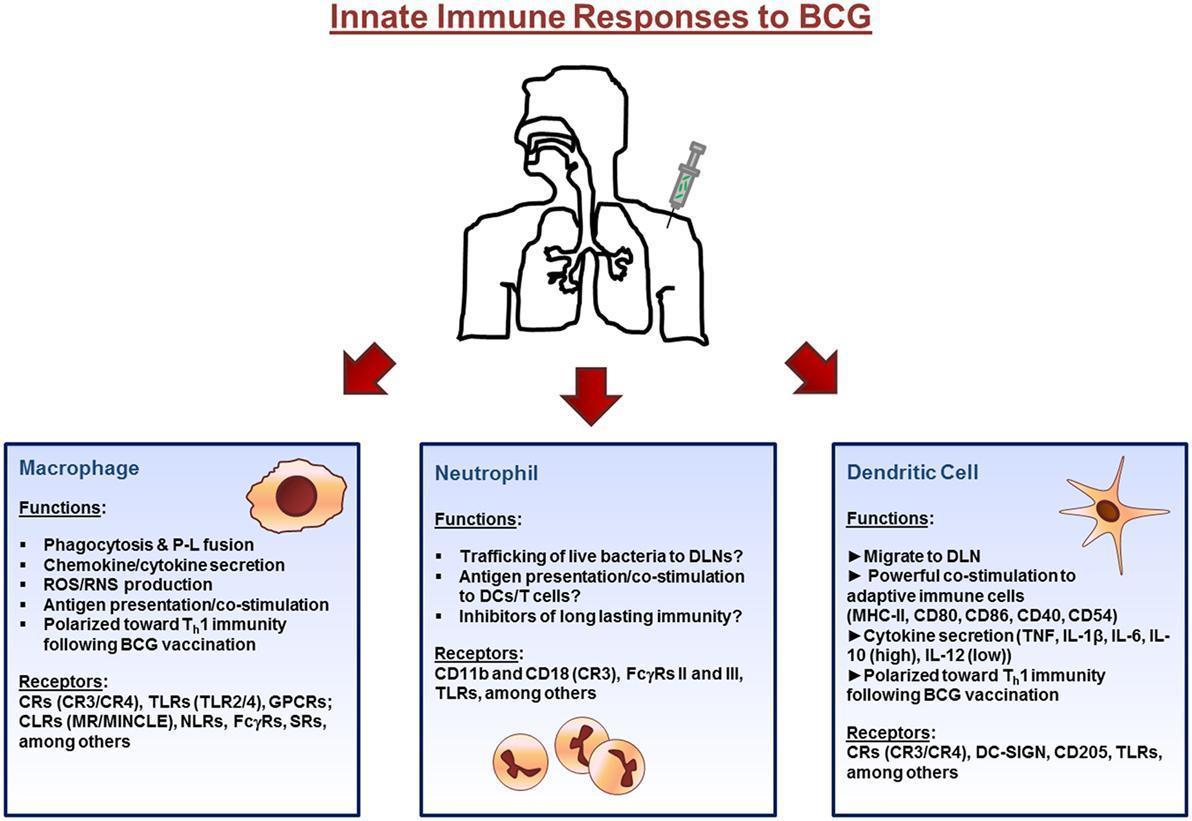

- Figure 1 shows the initial immune response to BCG that occurs at the site of inoculation (usually the dermal layer of the skin) where resident macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) interact with the bacillus via different receptors expressed on their surface.

- Macrophages and DCs phagocytose the bacteria initiating the innate immune response through the secretion of immunomodulatory components such as cytokines and chemokines.

- Bacteria are degraded via intracellular killing mechanisms and their peptides are trafficked to the plasma membrane along with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II where they are presented to cells of the adaptive immune system.

- Neutrophils also enter the site of inoculation and participate in the response.

- Finally, DCs, loaded with bacteria, and expressing antigen on their surface, home to draining lymph nodes.

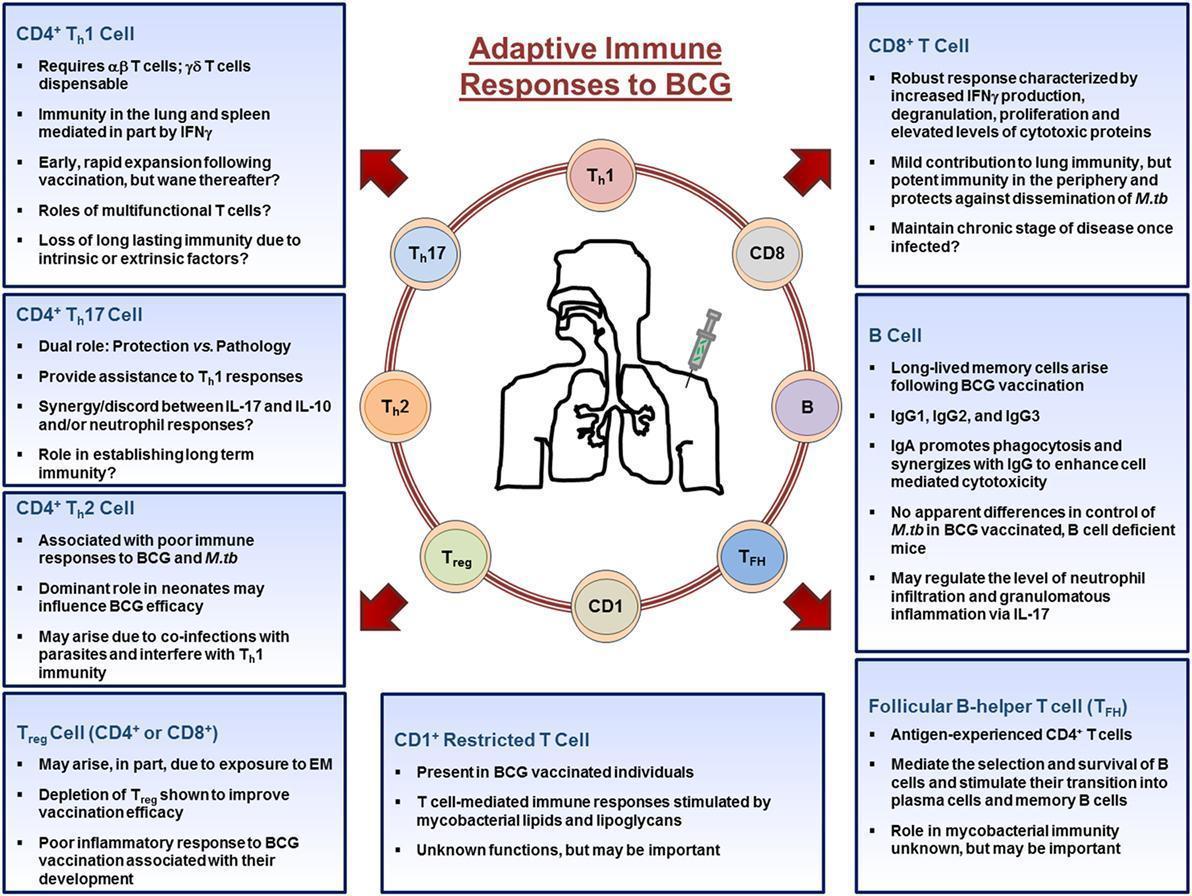

- Upon entering the lymph nodes, dendritic cells stimulate CD4+, CD8+, CD1+-restricted T cells, TFH, T regulatory cells, and B cells (shown in Figure 2).

- CD4+ and CD8+ T cells migrate out of the lymph nodes toward the site of inoculation and provide the necessary stimulation to innate cells.

- CD4+ T cells differentiate into Th1, Th17, or Th2 cells depending on the stimuli present in their microenvironment and aid in the activation of macrophages, whereas CD8+ T cells mediate their functions by lysing infected cells or by secreting cytokines.

- B cells differentiate into antibody producing plasma cells or memory B cells.

- Throughout the process, memory cells arise from those that responded to the infection and populate peripheral organs, such as the lung.

- Together, the cells of the adaptive immune systems orchestrate the immune response in an attempt to establish mycobacteria immunity.

Quiz

Download the Presentations from this section:

Related Talk

Richard Koup, NIH – Germinal centres and tfh cells

Associated Case Study

Adverse event following routine vaccination – Arthus Reaction

References

- KAZMIN, D. et al. 2017. Systems analysis of protective immune responses to RTS,S malaria vaccination in humans. PNAS. 114: 2425-2430.

- RTC, S Wikipedia

- LONG, C.A. & ZAVALA, F. Malaria Vaccines and Human Immune Responses. 2016. Current opinion in microbiology. 32:96-102.

- MOLIVA, J.I., TURNER, J. & TORRELLES, J.B. 2017. Immune Responses to Bacillus Calmette–Guérin Vaccination: Why Do They Fail to Protect against Mycobacterium tuberculosis? Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 407.

- HANEKOM, W.A. 2005. The immune response to BCG vaccination of newborns. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1062:69-78.