- Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a dsDNA virus, is a member of Bentaherpesvirinae with a ~236kb genome that expresses ~> 750 protein encoded from open reading frames(OPF) that emanates from complex control of transcription and splicing. (Picarda & Benedict, 2018)

- HCMV is carried by 70-100% of the world’s human population (Soderberg-Naucler, 2006) but its replication is species specific due to mechanisms used in evading immune response.

- In contrast to lack of symptoms and generally subclinical levels in immunocompetent individuals, immunosuppressed individuals experience acute HCMV infections with adverse signs and symptoms.

- HCMV has emerged as an important pathogens in individuals with AIDS and patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy after organ and bone marrow transplant.

- From these patients, the role of HCMV has been highlighted in the development of other inflammatory associated diseases such as autoimmune diseases, vascular disease and more recently certain forms of cancer.

- Epidemiological evidence has associated HCMV with long-term complications such as bone marrow failure and autoimmune-like disorder graft-versus-host diseases in recipient of bone marrow transplant; atherosclerosis and transplant vascular sclerosis (TVS) in solid organ recipient.

- Current research has been dedicated to determine whether that HCMV is a causative agent of the above mentioned diseases or is just an epiphenomena of inflammation.

- HCMV has three distinct stages namely: systemic replication phase in peripheral tissue, tissue localized persistent phase and multisite latency.

- Throughout the above mentioned stages, numerous proteins of HCMV are devoted to control central function of both innate and adaptive immune response by influencing the regulation of vital cellular processes that include cell cycle, apoptosis, migration, tumour invasiveness and angiogenesis.

HCMV and the Immune System

- During an active infection of HCMV, virtually all organs and cells can be infected. However, the ability of HCMV to replicate in the cells differs from one cell to another especially those in the immune system. For example, fibroblasts are considered effective host cells for viral replications compared with macrophages, dendritic cells and other cells such smooth muscle cells, hepatocytes, endothelial cells, epithelial cells and neuronal cells.

- HCMV DNA detection without viral gene expression in monocytes have been defined to be latently infected with the virus especially in seropositive individuals.

- Contrary, infected macrophages express late viral genes especially from patients suffering from HCMV. Moreover, these viruses can replicate in differentiated macrophages affirming that the ability of viruses replicating in macrophages is dependent on the state of cellular differentiation.

- Monocytes and their derivatives (Monoblast and promonocytes) and macrophages are heterogeneous population of terminally differentiated cells of the myeloid lineage that serves an ideal residence for latent virus that requires immune response for activation.

- HCMV have been found to replicate in macrophages which differentiate from monocytes stimulated by cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α.

- Even though its insufficient,TNF-α activates the HCMV immediately early promoter (IE) in myeloid cells hence enhancing viral replication. On the other hand, in fibroblasts, HCMV infection induces translocation of nuclear factor-KB which interact much faster, within hours, with the IE promoter.

- Thus, TNF-α production may enhance replication of HCMV in other cells through secondary activation of NF-KB.

- The above hypothesis have been supported by determination of high serum levels of TNF-α in patients with atopic dermatitis or sepsis. More so, HCMV is commonly reactivated with simultaneous increase in TNF-α after acute rejection of organ transplant as well as after acute graft-versus-host disease in bone marrow transplant recipient.

- In organ transplant recipients immune response against latent infection, production of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α by CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes, and other soluble cytokines play a critical role in differentiating latent infected monocytes into tissue macrophages that reactivate the virus.

- It is worth noting that the immune specific response against persistent HCMV infection is strong and increases with age through expansion of CMV specific-T cells dominated by late effector cells with relatively limited function (phenomenon called memory inflammation) (Maecker, 2017).

HCMV Influence on the Immune System Recognition

- During persistent HCMV, CMV evolves mechanisms that enables its co-existence with its host such as; avoidance of immune recognition as well as utilizing specific immune functions for its own reactivation and spread of virus.

- Such mechanisms include:

- Reduces the levels of expression of MHC class I and class II molecules on the surface of immature DCs

- Alters their pattern of cytokine secretion

- Suppresses their capacity for allogeneic immunostimulation

- Reduces the ability of DCs to stimulate cytotoxic T-cell responses to other viruses

- Inhibits the maturation of DCs and impairs the migration of immature and mature DC in response to chemokines in vitro

- HCMV-infected DCs may thereby blunt the antiviral activity of CTLs by inducing apoptosis in activated-T cells

- HCMV-encoded homologue of IL-10, cmvIL-10 suppress the functions of DCs and monocytes and impair their ability to activate T cells.

- Such virus-induced paralysis of APCs would be a powerful tactic for delaying or even preventing the generation of virus-specific T-cell clones

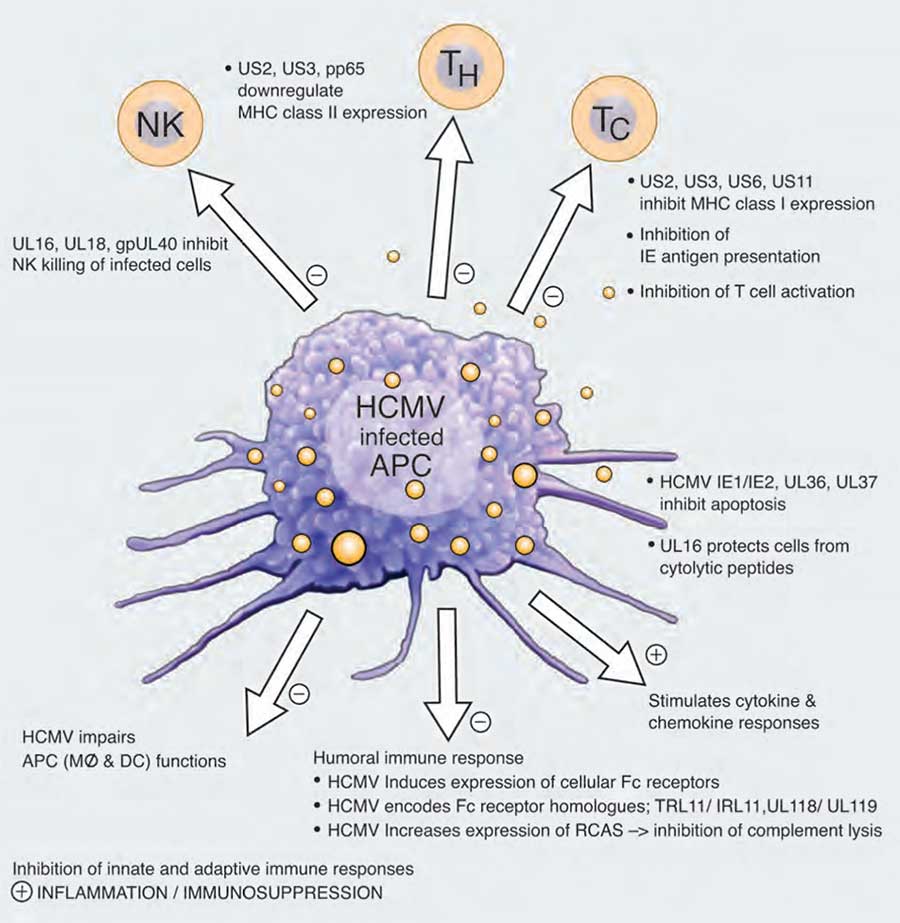

- HCMV also interferes with antigen-presenting pathways as shown in Figure 1.

production of viral proteins that inhibit NK cells responses, helper T and cytotoxic T cell responses as well as mechanisms that target the humoral immune response. The virus also controls the production of cytokines and chemokines and can stimulate local inflammation. However, at the same time infection of the host by this virus often leads to a general suppression of the immune system. [Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? Soderberg-Naucler, 2006]

- HCMV utilizes Fc receptors to avoid antibody binding through encoding their own Fc receptors homologues and expression of Fcγ receptors that binds to Fc region of IgG.

- HCMV-encoded Fc receptors may hide antigenic structure by coating the virus-infected cell surface with IgG antibodies preventing complementary interaction and antibody mediated cellular cytotoxicity.

- HCMV induces the expression of regulators of complement activation such as CD35, CD46 and CD55 protecting infected cells from complement-mediated lysis.

- HCMV infection induces different cytokines and chemokines that include IL_10, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-b, TGF-β, MCP-1, MIP-1α&β and RANTES.

- HCMV also triggers production of inflammatory cytokines through interaction with TLR2 and CD14.

- HCMV genomes encodes for two chemokine homologue, UL146 and UL147 that recruit neutrophil to site of infection. In addition, HCMV genome encodes four chemokine receptor homologue UL33, UL78, US27 and Us28 that are capable to bind and reduce the extracellular levels chemokines such as MCP-1 and MCP-1a thereby inhibiting recruitment of inflammatory cells to infected tissue.

HCMV and Cancer

- Recent evidence shows presence of genomes and antigens of HCMV in certain malignant tumours, EBV-negative Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cervix cancer, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma.

- In contrast, non-cancer cells within the environment of tumour cells are HCMV negative suggesting that this HCMV cannot transform normal cell lines into carcinogenic cells.

- HCMV may contribute to tumour progression by oncomodulation through the production of viral proteins that affect cellular differentiation, gene expression, DNA replication and cell cycle progression.

- HCMV have been implied to increase tumour invasiveness through increased migration of infected tumour cells.

- The above mentioned mechanism of evasion of immune response leads to immunosupression that negatively affect the host immune response against growing tumours.

- Virus-infected tumour cells increase their chance of survival through expression of HCMV-encoded anti-apoptotic proteins.

- HCMV protein UL16 may confer resistance against cell lysis mediated by NK cells and T cells.

- The above prevents the effectiveness of chemotherapy and immunotherapy that are considered to be treatment of these patients.

- Viral protein IE72 and IE86 of HCMV infection are expressed during the initial phase of the infection can bind to members of the retinoblastoma family of proteins called the pocket proteins p107, p130 and pRb resulting in alleviation of the repression of E2F-dependent transcription. Furthermore binding of pp71 to retinoblastoma induces DNA synthesis in quiescent cells.

- IE86 protein has been reported to interact with tumour suppresor protein p53, a cell cycle regulator involved in cell arrest, response to DNA damage and apoptosis.

- Following HCMV infection, levels of proto-oncogenes c-myc, c-fos and c-jun as well as of cyclin E and cdks are rapidly upregulated.

Quiz

References

- Maecker, H. (2017). Opening the Door on the CMV Immune Response in Aging. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 215(8), 1179-1180.

https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix081 - Picarda, G., & Benedict, C. (2018). Cytomegalovirus: Shape-Shifting the Immune System. The Journal of Immunology, 200(12), 3881-3889.

https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1800171 - Soderberg-Naucler, C. (2006). Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? Journal of Internal Medicine, 259(3), 219-246.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01618.x